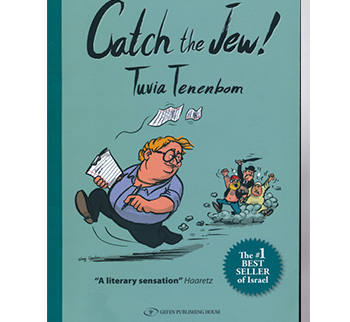

As Tuvia Tenenbom amply demonstrates in Catch the Jew, a new book that has become a bestseller in Israel, the Jewish state attracts scores of leftist writers, NGO activists, diplomats and other self-professed neutral observers whose baggage overflows with morally superior attitudes and a visceral antagonism toward Israel and the Jewish People.

Born into an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family in Israel, Tenenbom left at a young age for a new, less austere lifestyle in New York, where he has become a writer for American and German publications as well as founder of the Jewish Theater of New York. Because he speaks fluent English, Hebrew, Yiddish, Arabic and German, he can easily pass for a German-Christian writer and readily adopts this and other guises in Catch the Jew. His object is to go undercover to catch out the lies, conceits and deceits of the anti-Israel rabble before they, in turn, catch him out as a Jew. The book comes on the heels of his 2012 German book I Sleep in Hitler’s Room, based on a six-month walking study of modern Germany.

A gonzo and very politically incorrect journalist, Tenenbom excels at harpooning figures large and small who indulge in hateful rhetoric toward Israel, whether situated in the pro-Palestinian camp or on the Jewish left. An equal-opportunity reporter, he also catches rabbis, settlers and others on the extreme right of the spectrum. His modus operandi is to skewer them on the barbs of their own ridiculous claims.

This proves particularly easy during an interview with PLO executive Hanan Ashrawi, who utters many historically false statements. For example: “Palestinians have been living on their land historically for hundreds and thousands of years.” In Ashrawi’s mangled version of history, there was not a Jewish state here and probably not even a Jewish Temple here in biblical times.

She boasts that Palestine has always been pluralistic and has the “longest Christian tradition in the world.” But when Tenenbom points out that Christians once comprised 20 per cent and now less than two per cent of the Palestinian population, Ashrawi becomes agitated. Like many anti-Israel propagandists, she hates being called out in a contradiction or lie. “Oops,” Tenenbom observes. “This means that after Israel’s withdrawal, it was the Muslims who kicked out the Christians, the truest Palestinians. The argument she has built against Israel is collapsing with one fell swoop.”

On the Jewish side of the equation, Tenenbom meets Ha’aretz journalist Gideon Levy in Tel Aviv. Thinking he has a sympathetic ear, Levy asserts that the Jewish belief that they are the Chosen People and better than everybody, in addition to being the greatest victims of history, is blatantly racist. He doesn’t report on Palestinian terrorism or human rights violations, he says, because “what the Palestinians do is none of his business.”

When Tenenbom discovers that Levy doesn’t speak Arabic and relies on translations to know what the Palestinians are saying, he points out that Arabic speakers “speak in two languages, one amongst themselves and one with foreigners, and that if you don’t know their mother tongue they will sell you tall tales. Even Al-Jazeera is doing this, giving two very different viewpoints: one for the ‘brothers’ in Arabic, and one for Westerners in English.” Tenenbom does not mince words in his conclusion that Levy “is the biggest kind of Jewish racist that has ever existed… the strangest self-hating Jew you can find.”

If Tenenbom is an agile game hunter, Ashrawi and Levy are but two of the many trophy heads that he has the right to hang on his wall. A satirist who retains his sense of humour despite his dark subject, he goes after dozens of other interview subjects, some of whom also go after him.

A BBC news report tells of a French diplomat who is hurt by Israeli soldiers while attempting to deliver aid to Bedouins in the West Bank. Tenenbom investigates the report and readily debunks it as fiction. He shows that the International Committee of the Red Cross is just one of numerous agencies and NGOs that are complicit in attempting to damage Israel’s international reputation. (No surprises there.)

Being unapologetically politically incorrect, he asks “a really stupid question: Why are diplomats taking on an activist role in a host country? Is this what diplomats are supposed to do? I live in New York, where the UN is headquartered, and naturally there are many, many diplomats in New York. Should I expect them to come to Harlem and stop any eviction notice against members of the black community by the New York courts?”

Tenenbom interviews people of every political stripe on all sides of the battle lines. He has a capacity to befriend people wherever he goes and engage them on a deep level of conversation; sometimes, he professes friendship for people whose politics he disdains. Sadly, but not unexpectedly, he finds that Jews can harbour prejudice and hatred in their hearts as readily as any other people. One of the ugliest examples of this involves an Israeli guide who escorts European groups through Yad Vashem, using the story of the Holocaust as a platform from which to deliver poisonous propaganda about modern Israel.

Tenenbom visits Hebron (twice, on both sides of the Arab-Jewish divide) and many other places from the Golan Heights to Eilat. In Jenin, he meets a noted Palestinian journalist, Atef, and goes to a village where house demolitions supposedly took place. In this, as in all Palestinian narratives, the Israelis are the villains. When Tenenbom suggests a different truth, Atef accuses him of being Jewish or at least of paying the Jews money. In Atef’s version of history, the Jews invented the Holocaust and Germans paid them compensation for something that never happened. Atef is a leading field researcher for B’Tselem, the activist organization of the Israeli left, and has also served as Gideon Levy’s guide and translator.

In Bethlehem, Tenenbom meets Rula Ma’ayah, yet another Christian female Palestinian minister, who declares that the Christians left Bethlehem “because of the occupation.” Where are all the Muslim female ministers in the Palestinian government-in-waiting? Tenenbom does not address that question, but he does point out that western feminists on the left bash Israel and uncritically support the Palestinians despite the latter society’s appalling treatment of women.

Tenenbom meets two medics from Doctors without Borders whose role is “making up diseases so they can stick it to the Israelis.” A Druze man tells him that Jewish nationalism is racism, “but the Arabs have a right to have a land of Arab nationality because this is not racism. I ask him to explain this obvious discrepancy to me but for the life of him he can’t.” He attends an Israeli-Palestinian peace dinner in the home of then-Israeli president Shimon Peres, which he concludes is a sham because no Palestinian Muslims from the territories are present. “What happened to this country while I was away?” he concludes. “Even its president is a deluded man.”

Tenenbom reserves his sharpest criticism for supporters of the many European NGOs, agencies and foundations that have acquired a knee-jerk prejudice against Israel as a result of prolonged exposure to misinformation and propaganda. “You cannot – repeat: cannot – criticize peace lovers,” he writes. “They have a monopoly on compassion and truth, and they staunchly demand their basic human right to state their opinion without anybody uttering another word once they have spoken.”

His second favoured target is the leftist Jew, who “is the most narcissistic of people that I’ve ever met. There’s not a single moment, day or night, that he’s not fully busy with himself or with other Jews. There’s nothing on his agenda except his obsession to find fault with himself and his tribe. He just can’t stop.”

Although Catch the Jew may seem long, circular and repetitive at times, Tenenbom certainly knows how to hammer home his points, occasioning a certain satisfied recognition in the minds of those readers whom he hasn’t offended. He returns home from each interview to the comfort of his garden in Jerusalem, where he takes solace in feeding a group of feral cats, who lap up whatever he gives them with pleasure and gusto.