In honour of Canada’s 150th birthday, The CJN presents essays on 10 significant moments in Canadian Jewish history.

In Jewish circles, Oslo, Norway, is commonly known as the place where a historic peace accord was secretly brokered between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1993. The Norwegian capital was also the site where the two sides’ representatives would be honoured with the Nobel Peace Prize the following year, “for their efforts to create peace in the Middle East.”

Oslo and Stockholm, Sweden – where Nobel Prizes are awarded for contributions to the fields of physics, chemistry, medicine, literature and economics – have played host to the achievements of many Jews. Despite comprising about 0.2 per cent of the world’s population, or about one out of every 500 people on Earth, those of at least half-Jewish ancestry account for more than 22 per cent of the 885 individuals exalted with the title of Nobel laureate.

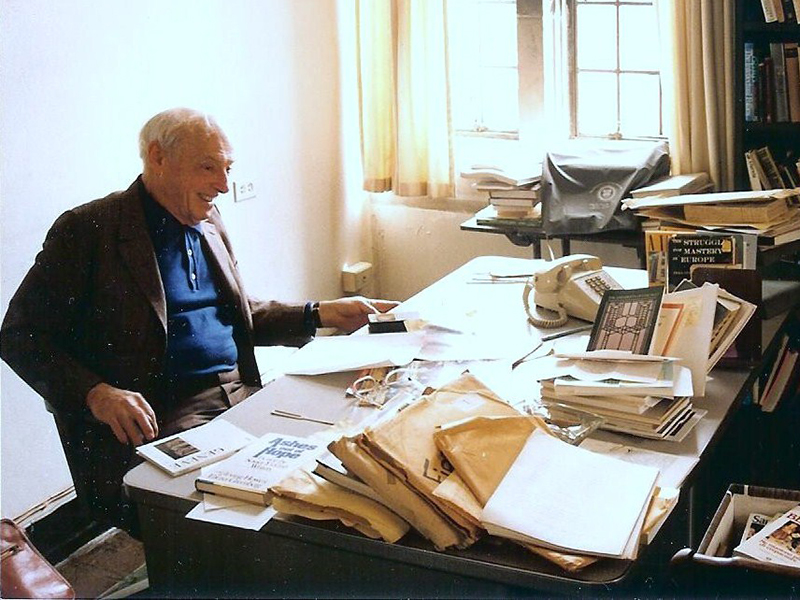

Canadian Jews have similarly overachieved, even though they constitute just over one per cent of the country’s population. Five of Canada’s 18 Nobel Prize winners have been Jews: Saul Bellow for literature in 1976, Sidney Altman and Rudolph Marcus for chemistry in 1989 and 1992, respectively, Myron Scholes for economics in 1997 and, most recently, Ralph Steinman for medicine in 2011. However, like many Canadians seeking glory on the world stage, this celebrated group had to venture south to the United States to gain recognition.

“I knew that if I wanted to grow and achieve my potential, I should attend a school where I could learn from and work with those who were the best and who could bring out the best in me,” wrote Scholes of his decision to attend graduate school at the University of Chicago. Scholes, the only Canadian Jewish laureate not to hail from Montreal, was born in Timmins, Ont. He obtained his undergraduate degree in economics from McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., where his family moved when he was 10. After his time in Chicago, he would join the Stanford University faculty and, later, rise to the role of managing director at U.S. investment bank Salomon Brothers, before co-founding his own Connecticut-based hedge fund firm, Long-Term Capital Management.

Altman echoed Scholes’s sentiment in his own Nobel biography. Despite growing up in the Montreal suburb of Notre-Dame-de-Grâce and intending to enrol at McGill University after high school, Altman ended up completing his undergraduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he “experienced four years of overstimulation among brilliant, arrogant and zany peers and outstanding teachers.” He would go on to earn his PhD at the University of Colorado and work in prestigious laboratories, before climbing through the professional ranks of Yale University.

Except for a six-year stint in Detroit during his childhood, Marcus remained in Canada until necessity drove him south of the border. After receiving his PhD from McGill and participating in a post-doctoral program at the National Research Council in Ottawa, Marcus made a switch from experimental to theoretical chemistry, which required leaving the country, as “there were no theoretical chemists in Canada at that time.” He would accept a second post-doctoral research fellowship at the University of North Carolina and eventually make his way to the California Institute of Technology, where he was working when he was awarded the Nobel Prize “for his contributions to the theory of electron transfer reactions in chemical systems.”

The laureates’ experiences are reminiscent of the experiences of many Canadian Jews, with most of their parents having immigrated to this country and subsequently worked hard to build a better life for their families.

“My mother worked in a textile mill and my father in a grocery store before they met and married,” wrote Altman. “It was from them that I learned that hard work in stable surroundings could yield rewards, even if only in infinitesimally small increments.

“For our immediate family and relatives, Canada was a land of opportunity. However, it was made clear to the first generation of Canadian-born children that the path to opportunity was through education. No sacrifice was too great to forward our education and, fortunately, books and the tradition of study were not unknown in our family.”

Bellow’s parents came from Russia in 1913 and settled in a multicultural part of Montreal, which was home to fellow newcomers from Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Greece and Italy. Perhaps this cultural mosaic contributed to Bellow’s aptitude for languages, as he became fluent in English, French, Hebrew and Yiddish at an early age.

In Russia, Bellow’s father had been an importer of luxury produce, such as Turkish figs and Egyptian onions. Once in Canada, he opened a business as a self-employed “produce broker,” but fell on hard times and turned to bootlegging, which got him in trouble with some disreputable people and forced the family to flee to Chicago when Bellow was nine.

When Bellow later attended Northwestern University, as he was trying to figure out what his next step would be after school, the English department chair tried to dissuade him from pursuing his plans to study the language. “No Jew could really grasp the tradition of English literature,” he told Bellow, who would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize, multiple National Book Awards and many other honours in addition to the Nobel Prize.

Steinman’s parents emigrated from Eastern Europe and opened a department store in Sherbrooke, Que., about 150 kilometres east of Montreal. Though his father wanted him to continue in the family business, Steinman would graduate near the top of his class at the Harvard Medical School and become a pioneer in biomedical research at Rockefeller University in New York City.

Steinman used treatments derived from his prize-winning discovery of a previously unknown class of immune cells, to combat his own pancreatic cancer for more than four years. However, even in death, Steinman proved to be among the rarest elite. Following a rule change in 1974 that barred the prize from being bestowed posthumously, Steinman became the first deceased person in half a century to be honoured as a laureate, as the Nobel Committee had been unaware of his passing three days prior to its announcement of the award.