Oftentimes, discussions about the complicity of Poles and others in the Holocaust takes place without any mention of the Germans.

This has been an issue ever since the first accounts of the Holocaust were published. And with good reason: because survivors may not have had much direct contact with Germans, they had more to report about being a Ukrainian kapo or hiding in the Polish countryside than about the German army detachment that was overseeing the atrocities.

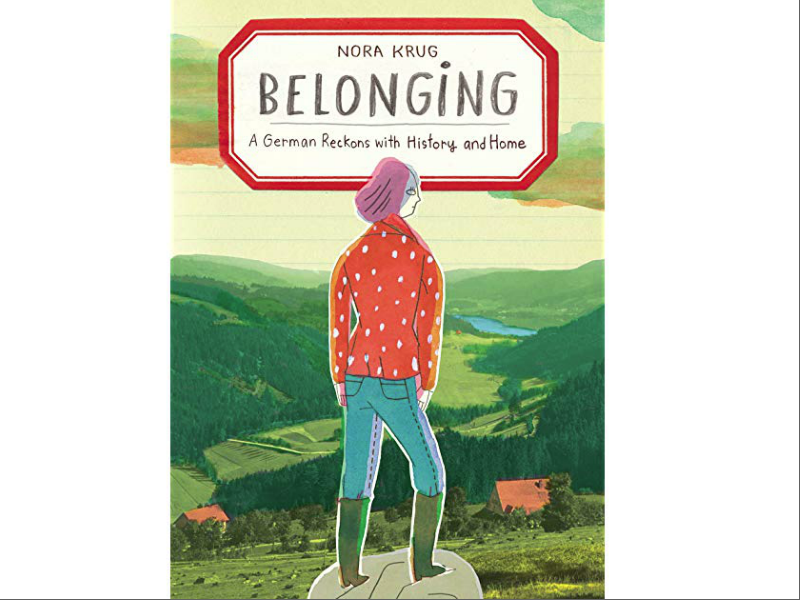

There are always exceptions to this rule, however. There are many works that strive to place the perpetrator more purposefully at the centre of Holocaust research and art. This year in cinema, for example, there is a new dramatization of the capture of Adolf Eichmann called Operation Finale. Among the impressive efforts in book form is Nora Krug’s graphic memoir, Belonging: A German Reckons with History and Home.

Rising hard-right activity in Germany, including recent elections in Bavaria, beside images of white supremacists marching in Donald Trump’s America, have reasserted the need to look at the German, and German-inspired perpetrators.

Krug is German-born, a child of the last decade of a divided Germany. Her childhood backyard in Karlsruhe, in southwest Germany, overlooked an American military base. Belonging includes a photograph of her as a toddler with her mother, watching an American plane taking off behind their fence. To this image, Krug appends the admission that throughout her “childhood, the war was present but unacknowledged.”

Krug is young enough that her parents’ responsibility can be said to go as far as their silence. Yet among her grandparents’ generation, possibilities for guilt and responsibility abound. Her father’s older brother, an 18-year-old inductee in the German war effort, was a similarly under-discussed part of her family heritage.

Krug’s uncle’s death fighting in Italy in 1944 is marked by her reproduction of the death announcement that was sent out by his family. It offered, as Krug translates it, a commemorative appreciation of young Franz Karl Krug for giving “his young life to his beloved Heimat on July 19, 1944, while loyally performing his duty at the southern front.”

Even more provocative are the prewar and wartime activities of her maternal grandfather.

Krug re-entered this family story after leaving it far behind, having moved to Brooklyn, where she established herself as a graphic artist and found a Jewish husband. Her immediate family remains far in the background, as does life in the U.S., as Belonging allows her to present a clear picture of Karlsruhe and the rest of Germany under the Nazi regime.

READ: JEWISH PRAYER IN A SAD AND BEAUTIFUL CITY

In Belonging, Krug makes use of an impressive array of graphic tools: drawings, historical and family photographs, and found objects like her uncle’s death announcement and his sixth-grade exercise books. The latter, filled with neat German script and illustrated with cleanly rulered and coloured swastikas, offers a rare unpacking of the family inheritance that could be said to define key aspects of 20th-century German identity.

Krug translates and embellishes these artifacts, making them legible to us, while adding her own pencilled and drawn contributions to what becomes a weighty scrapbook devoted to her family’s past.

A consideration of the German idea of Heimat, or homeland, is set upon a collection of sepia-toned historical photographs. The postwar milieu is conveyed with popular magazine articles. Her grandfather’s American Denazification file from 1951 is reproduced as a part of her circuitous search to understand what sort of Nazi fellow-traveller he was.

Most of the book’s pages have their own illustrative ingenuity, their own colour schemes, their own mixture of hand-written text and images. The outcome is an imaginative response to events that took place far away from Krug’s own experience.

Belonging is a sustained meditation on Germans. It brings their faces into view; it examines their intimate objects, family photographs and journals.

Near the end of the book, the story of Jewish survivors entwined with Krug’s grandfather’s wartime experience is sensitively told. This presents a coda to the mystery of her grandfather’s wartime doings. But in this material there lurks an appreciation of how difficult it is for Jews and Germans to look at each other.