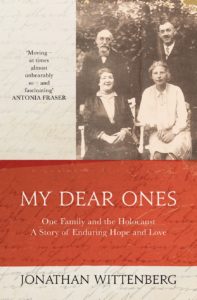

Touted as one of Britain’s greatest religious thinkers, Rabbi Jonathan Wittenberg was born in Glasgow, Scotland to refugees from Nazi Germany. He is currently the spiritual leader of the New North London Synagogue and senior rabbi of Masorti Judaism U.K. He is the author of the highly acclaimed book My Dear Ones: One Family and the Holocaust – A Story of Enduring Hope and Love, a moving tribute based on correspondence he discovered that was written by his family throughout the war years.

The CJN interviewed him by telephone from London, England.

What are the origins of My Dear Ones?

After my father’s sisters died, I was tidying their flat in Jerusalem, where they had lived since 1938 or 1939, soon after they fled from Germany to Palestine. I found one of those old, wooden trunks, and in it was a bundle of letters. I immediately realized they were letters between my father’s mother, her siblings and her own mother during the terrible years of 1937 and 1938. There were even letters from 1942 and after the war. I took them home.

Soon after, my father died and, perhaps as a tribute to him and the family’s history, which I didn’t know well, I began to work on the letters – to read them, to translate them into English, to put them together in a timeframe – and I realized that they told the story of a well-known rabbinical family in Germany and described the different destinies of the six siblings, their mother and great-grandmother.

Of the six, three made it to Palestine, one eventually to America and two perished. My great-grandmother died at Auschwitz. And I was able to research the detailed background behind some of those letters and was able to tell the unfolding narrative of the Holocaust – some of its politics, some of its key developments, how the death camps arose – and to show their impact on the different members of a single family through what their letters to each other said – and what they didn’t say – and what eventually happened to those members of the family.

Was it painful or frustrating for you to go through those letters?

More than either pain or frustration – both of which were there – was some sort of compulsion. I felt I was describing the lives of my family, of which I had little knowledge, and I was driven by compulsion to find out. I read very widely. I looked at footnotes. I read bibliographies. I tried – sometimes with success and sometimes with a frustrating lack of success – to contact local historians and archives. I couldn’t actually stop. It was a completely compelling process.

I’ll give you a couple of examples of some of the details that moved me – the very ordinary details of their lives. For example, in the summer of 1938, my father’s aunt Sophie lived in Moravia, in what was then Czechoslovakia. She wrote home to her family about the garden. She was very wealthy. She and her husband had no children. And she wrote about all the fruit she bottled and the jams that she made. And I remember my father teaching me to bottle fruit. Since I read that letter, each year now, I have bottled fruit in memory of my father’s aunt Sophie. Their lives really touched me.

Do you feel the book has offered you some closure?

I’ve got mixed feelings about the word “closure.” I don’t think in life that there is closure. I would put it the other way around: it has offered me openings. I have met people who are relatives I didn’t know I had. I also met local people from that town in the Czech Republic. I took a group from my synagogue there two years ago. I think it may have been one of the first Shabbat services in the one synagogue there that survived, maybe the first Shabbat service since 1942. My aged mother is glad that interest is being taken in these people now. So this has opened doors and fostered connections with people.

I think Canada is an example to us all, which is: what is the state of refugees today? It’s brought me close to those issues. Partly as a result, we hosted a refugee in our home for half a year, until he was able to successfully move on in life. So the book is about the past, but it’s also very important for me that it has relevance today. It’s about the fate of people who were persecuted for who they are, as they sought to create a future for themselves and their families in a new land.

READ: ‘A LOT OF SADNESS’ OVER CLOSURE OF ACT TO END VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

Your newest book is titled Things My Dog Has Taught Me. What are some of those things?

The book began in a light-hearted manner, because I said to my publisher and agent, “I could write about my dog.” And they said, “That’s excellent. People like dogs and the British have got a reputation for loving dogs.”

My dog has taught me about the values that really matter: loyalty, friendship, listening, kindness. I also learned from the dog about abandonment. Our first dog was found in the street. What did that mean, to be traumatized? I also write about grief, fear of the death of a pet and what happens afterwards. And, in fact, had I been writing a book about what it means to try to be a pastoral rabbi who cares about people, I would have written about many of the same themes.

How would you describe the mood of British Jewry these days?

By and large, life is really OK for Jews in Britain, but we have deep concerns about anti-Semitism. It is not acute, violent or a constant feature of our lives, by any means. But the Labour Party has been a particular focus of concern, as has its leader Jeremy Corbyn’s failure to deal with it clearly and unambiguously. I attended a gathering in Parliament Square in London called at almost no notice, but very well attended across the Jewish community, calling on the Labour Party to be clear in its condemnation and response to anti-Semitism and all forms of racism.

The bigger concern, I think, is that the world is not in a good way. It’s a much more frightening world than I think it was five or seven years ago. I have a very strong view that Brexit is not a good thing. Most, if not all, of the Jewish community shares that view. The policies of Russian President Vladimir Putin are extremely frightening, as often are the policies of U.S. President Donald Trump. The situation in the Middle East is stagnating.

Is it known how British Jews voted in Brexit, and how will its passage affect the community?

The latter question I really don’t know. No one really knows how much it’s going to have an effect, and the nature of the deal remains quite unclear. If it’s a soft Brexit, it will make little difference.

I’ve heard that 70-something per cent of the Jewish community voted to remain in the U.K. My mother, who was a teenager in Frankfurt during the Nazi years, felt very strongly that the whole campaign has allowed racism to re-emerge into the discourse. And that’s a very frightening feature of our world – a sense of nationalist xenophobia and religious fundamentalism. These things are on the rise and may reverse some of the real democratic gains of the Enlightenment. So these are disturbing times. Far from specifically and exclusively for the Jewish community, these are troubling times for humanity.

This interview has been edited and condensed for style and clarity.