Gloria Lidsky Fuerstenberg,

Special to The CJN

On April 14, the last day of Passover 2012, like many Jews the world over I attended synagogue services. The Yizkor prayer of remembrance for the dead is a hallmark of this occasion. Included in the siddur are prayers for the souls of our departed parents and other family members, for those individuals who were murdered in the Holocaust, for people who perished in defence of the State of Israel and for the victims of terror.

What made this day different from all other days was the fact that it coincided exactly with the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic. In my hands, along with a siddur, I held a small, unique Yiddish prayerbook called a techinah (or tkhine, in Yiddish). In it were many prayers, including one to be recited for the memory of people who had drowned in rivers or at sea and, most dramatically for me on that specific date, for those who had died in the Titanic disaster.

I was stunned by a paragraph extolling the humanitarian virtues of Ida and Isidor Straus, a prominent German Jewish American couple in their 60s who went down with the ship. It read: “They had done much good in their life, going hand in hand to help the poor and downtrodden, to aid the elderly, the sick and the weak, and who were united in their death. ‘Where you go, I will go,’ said the noble woman to her husband, and she refused to save herself knowing that her husband would be drowned.” (My translation.)

Straus, the founder and co-owner of Macy’s department store in New York City, had also served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and was a noted philanthropist. According to surviving eyewitnesses whose names and statements are on record, including that of Ida Straus’s personal maid, a Miss Ellen Bird who boarded the lifeboat at their insistence, the couple chose to stay on the ship, he refusing to enter the lifeboat because there were still women and children who had not yet been evacuated, and she declaring her intention to stay with her husband to the end.

Last seen by passengers and crew who were already on Lifeboat 8, they sat calmly on deck chairs, holding hands. Ida Straus’s body was never found. Isidor’s remains were retrieved days later by the ship C.S. Mackay-Bennet from Halifax and were buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, N.Y.

The Titanic had set sail during one of the largest waves of Jewish immigration to the United States from eastern Europe, between 1881 and 1924. The majority of Jewish passengers, in third class, were refugees fleeing the dangers of European life such as pogroms and the three-year conscription into the Russian army, described by some as an ongoing pogrom “only much longer and much more painful” for Jewish soldiers because of rampant antisemitism.

Uniquely, the Titanic was the first great ocean liner to do away with steerage class and, as a result, many third-class passengers were treated to service and food they had never experienced. Apparently the White Star Line made a larger profit per head from third-class tickets and hoped that word of good treatment would spread and business would increase. Passengers in first class included those who, like the Strauses, were returning to America from vacations and business trips abroad or were immigrating with their families and household staff.

White Star, Cunard and German lines had separate kosher kitchen facilities by 1912, with meat and milk dishes and silverware identified as such in English and Hebrew, and kosher food available in all classes for those requesting it. These meals were instituted as the result of “a request from a number of Jewish organizations” and the fact that, according to an article in the Washington Post of Nov. 2, 1909, a young Jewish woman of 18 had died of starvation on arrival in Ellis Island by ship because she refused to eat non-kosher food.

The name of the special “Hebrew cook” of the Titanic was Charles Kennell, listed as 30 years of age. Of the 2,225 passengers, he was one of the 1,512 who did not survive. Religious supervision of the provisions on the Titanic was provided by the rabbi of Southampton, who also trained Kennell as a kosher supervisor.

My tkhine was printed in New York in 1916 by the Hebrew Publishing Company, just four years after the sinking of the ship, and this heroic episode was still fresh in peoples’ minds. Its particular prayer of remembrance for the Strauses is the only one out of the 176 to mention any contemporary, i.e non-biblical, individuals by name.

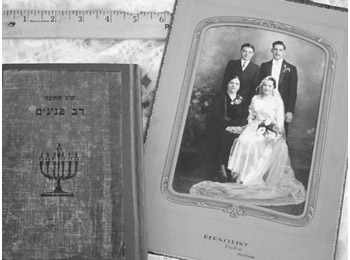

The 314-page volume had been purchased by my widowed maternal grandmother, Gittel Gorodetsky, soon after her arrival in Montreal by ship in 1926, from Beltz, Bessarabia, with her two youngest children, my mother, then a girl of 14, and my Uncle Reuben, 6. It was used for prayer daily by her and subsequently by my mother, Fanny Lidsky, of blessed memory. When my mother passed away in 1999, I started to explore this small volume as comfort, connection and consolation. My own day school (yeshiva) education had been in Hebrew, but I was able to read the Yiddish (luckily it had punctuation) and understand most of it.

What I discovered was a treasure of Jewish women’s thought and piety that truly reflected the innermost concerns of the women who composed and wrote them down. The word techinah, from Hebrew, means entreaty, supplication for favour, a request for the Almighty to be gracious. It also refers to the collections of such requests that had been compiled originally into small printed pamphlets and later into volumes used by Ashkenazi women in central and eastern Europe for private devotion from the 17th century on. The rise of printing in that era also saw women involved in production as printers, translators and even typesetters.

Structurally, each individual prayer begins with a heading directing when and sometimes how it should be recited (e.g. “Upon arising” or “With great devotion”). The first few words of every prayer in the techinah are in Hebrew in the somewhat impersonal language of the siddur, followed by a supplication in Yiddish in a woman’s voice addressed directly to God as one would speak to a loving father. This form is used for every occasion in a woman’s life, both domestic and in the synagogue – lighting the Sabbath candles, baking challah for Shabbat, blessing the new month (Rosh Chodesh) and hearing the shofar. Every day of the week has its own distinct private devotions.

What I found meaningful are the specific requests for heavenly protection for children or relatives in a war (remember this edition was printed during World War I), upon hearing bad news from the “Alter Velt” (Old World, or Europe), and for the souls of victims of fire and pogroms. There are also supplications to be read by an agunah (one whose husband refuses to give her a Jewish divorce and who therefore cannot remarry), by a woman who is being supported by her children – this is before social security when many elderly women had no personal resources and had to live with married children – and for a woman to meditate on before going out to collect charity on behalf of the needy. It expresses her fervent wish that she not, “Heaven forbid,” shame someone who cannot afford to give money nor somehow inadvertently embarrass the recipients of the charity.

This edition of the tkhine is unique because, having been published in 20th-century America, it reflects some of the guilt associated with breaking the commandment to honour the Sabbath. Employed in garment industry sweatshops to support their families, immigrants to America almost always had to work on Saturdays, even though it was against their religious beliefs. After begging for divine forgiveness on behalf of her husband and herself for this unwilling transgression, the reader prays for a better future in which economic security would allow them to once again honour the Sabbath completely.

The beauty of the language and the directness of expression in the tkhines are a testament to the literacy, intelligence and piety of Jewish women through the ages.