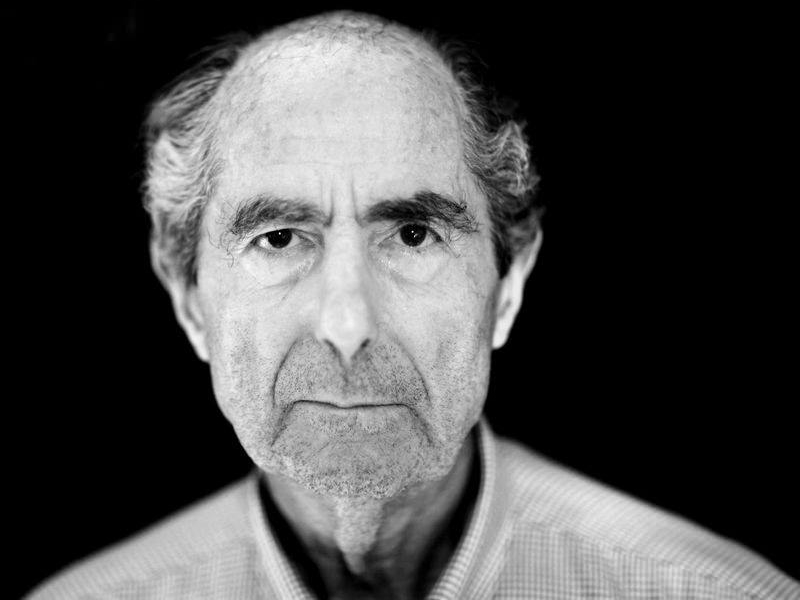

In the days following Philip Roth’s death, a host of writers were asked to name their favourite novel of his; the one that contributed to their own development as writers.

Many chose the ribald Sabbath’s Theatre, a 1995 book that is focused on sex. Others chose the more dour and dire American Pastoral, a lyrical portrait of the breakdown of a prominent Jewish New Jersey family in the Vietnam War era and after.

An equally pressing choice might be Roth’s 2006 novella, Everyman, which is wholly and devastatingly about death. Among Roth’s later works, it seems to foresee, uncannily, the writer’s own diminishment, due to age, illness and his decision to withdraw from writing.

Everyman employs none of Roth’s alter egos, but follows a nameless character who resembles them. He is the son of Jewish parents from Newark, N.J., who is retired from his Manhattan-based work in the advertising business. After September 11, he abandons New York City for the Jersey Shore, to paint and try to maintain, as best he can, his enthusiasm as an aging man.

But the narrator’s life is undone by disruption, estrangement and loss. He recalls the collapse of three marriages, and the anger his two sons felt about his divorce. In contrast, there is one thriving relationship: the narrator’s bond with a devoted daughter of his second marriage.

Roth’s narrator is haunted by the sense that his instinctive confidence and equilibrium have failed him. Illness becomes an overwhelming presence as he enters his 60s: “not a year went by when he wasn’t hospitalized. The son of long-lived parents, the brother of a man six years his senior who was seemingly as fit as he’d been when he’d carried the ball for Thomas Jefferson High … his health began

giving way and his body seemed threatened all the time.”

His parents’ deaths lead him to yearn for the intimacy of his youth. Everyman begins, graveside, with a portrait of the narrator’s father’s burial. This set piece, staged in a tumbledown New Jersey Jewish cemetery, is a tour de force. The funeral scene encapsulates Jewish life over a century and employs traditional funeral rites to convey the narrator’s dark view of death.

As his family attends to the job of refilling his father’s grave, one shovelful of dirt after another, Roth’s narrator considers the “burial’s brutal directness.”

His father was going to lie not only in the coffin, but under the weight of that dirt, and all at once, he saw his father’s mouth as if there were no coffin, as if the dirt they were throwing into the grave was being deposited straight down on him, filling up his mouth, blinding his eyes, clogging his nostrils and closing off his ears. He wanted to tell them to stop burying his father’s face.

Roth’s narrator refuses to put any “stock in an afterlife,” and though he values the intimacy of family life and appreciates his parents’ accomplishments, he is adamantly non-traditional when it comes to faith. He is sure, “without a doubt, that God was a fiction and this was the only life he’d have.”

READ: POUND’S SUPPORT OF FASCISM DIDN’T DETER HIS APPEAL TO AMERICAN POETS

Leavening Everyman’s bleak outlook is Roth’s wonderful way with characters and his ability to highlight complex themes using plainspoken language and sharp anecdotes. The retrospective view of lost intimacy with the narrator’s sexual partners is rich and deeply conceived.

The character’s father’s small jewelry store in the 1940s comes cinematically alive in the story. The variety in American Jewish life is conveyed by an account of regular visits by a Hasidic diamond merchant from New York City. The merchant “dressed in a large black hat and a long black coat of a kind that you never saw on anyone else.” The two men sat “behind the showcase chattering amiably in Yiddish,” before retiring to the back of the store to close a deal with a handshake.

With all its attentiveness to the richness of daily life, the spectre of death haunts Everyman’s conclusion. Its narrator has decided to visit New York to look into the possibility of moving back to the city. But on his way there, he takes a detour to the tumbledown cemetery, where his parents are buried. “He never made it to New York,” the book’s final section begins.

At the cemetery, he comes “upon a black man digging a grave with a shovel.… He wore dark coveralls and an old baseball cap, and from the grey in his moustache and the lines in his face he looked to be at least 50. His frame, however, was still thick and strong.”

This character offers Roth’s narrator his final lessons in life and death, which includes an account of how to dig a grave. The gravedigger’s commitment to his work is heightened by the fact that he dug the narrator’s parents’ graves.

A single grave, he explains, from down in the hole he is digging, is “a day’s work,” and “it’s got to be right for the sake of the family and right for the sake of the dead.”

In scenes like this, Everyman rises to the uncanny greatness we might expect from a Shakespearean tragedy, presented in plainspoken New Jersey language from the perspective of an aging Jewish existentialist. Roth’s closing scene is about digging dirt with craft and care. It is about 20th-century America. Its mastery is its combination of weightiness and readerly pleasure.