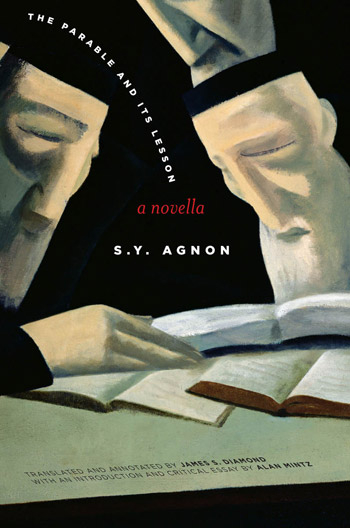

The Parable and its Lesson: A Novella

S.Y. Agnon

Stanford University Press

For readers familiar with S.Y. Agnon’s dazzling work, seeking an opportunity to re-experience the richly textured, ever-changing, kaleidoscopic literary immersion that is an Agnon story, or for those wishing to experience Agnon for the first time, there is cause for celebration. Agnon’s The Parable and its Lesson: A Novella has just been published as part of the Stanford Studies in Jewish History and Culture.

The Parable and its Lesson has two narrators who relate events that happened in the shadow of the horrific Khmelnitsky pogroms of 1648. It features a descent by a rabbi and his shamash into Gehinnom (Hell) to help save a woman from becoming an agunah (a woman unable to re-marry).

This mysterious trip to Gehinnom, however, is only one point of departure in the story. Like so many of Agnon’s works, The Parable and its Lesson takes the reader on an elaborate labyrinth journey. There are myriad detours: dissertations, discussions, homiletics, reflections and off-the-beaten-path side trips into a fantastical world of another time and place. We become entirely enveloped – some might say shrouded – as if in a giant, invisible tallit where the ancient is modern and the modern is an ordered jumble of tradition, fear, superstition, love, sacrifice, humility, haughtiness, cruelty and kindness. Agnon hides many of the nuggets of the story in this jumble and he does not make it easy for us to find them.

In 1966, Shmuel Yosef (S.Y.) Agnon, along with the Jewish German poet Nelly Sachs, received the Nobel Prize for literature. He is the only Israeli writer, the only Hebrew-language writer, to have won that prize.

In bestowing the award upon the 78-year-old writer from Jerusalem, Ingvar Andersson of the Swedish Academy made the following observation on Agnon’s works: “In your writing, we meet once again the ancient unity between literature and science, as antiquity knew it. In one of your stories, you say that some will no doubt read it as they read fairy tales, others will read it for edification. Your great chronicle of the Jewish People’s spirit and life has therefore a manifold message. For the historian, it is a precious source, for the philosopher an inspiration, for those who cannot live without literature it is a mine of never-failing riches… a combination of tradition and prophecy, of saga and wisdom.” Andersson knew of what he spoke.

Agnon died four years after receiving the award. But because of staunch Agnon enthusiasts and loyalists such as the late James S. Diamond, who translated The Parable and its Lesson, and Jewish Theological Seminary Prof. Alan Mintz, his work will live on. In the introduction to the book, Mintz described the story as “a truly exciting piece of literature that is unparalleled in the rest of modern Jewish writing.” He also wrote an instructive essay about Agnon that makes the Stanford University publication particularly attractive.

Suddenly, Love

Aharon Appelfeld

Schocken Books

Aharon Appelfeld has not won a Nobel Prize for literature, although he is entirely worthy of the distinction. He is the recipient of many honours and awards for his work, but none yet from the Swedish Nobel Academy.

Appelfeld’s volume of work is prodigious. He has written many works of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, literary criticism and other commentaries. That he writes in a language – Hebrew – that he acquired only after his arrival in Mandatory Palestine in 1946 at the age of 14, adds an additional measure of remarkability to the distinctive, penetrating quality of the stunning literature that flows from him.

Suddenly, Love (translated by Jeffrey M. Green) is Appelfeld’s latest instalment in what he has described as the “long saga about the Jewish people, about what happened to them during the 20th century.”

Suddenly, Love is the affecting, heart-rending story of Ernst, an ailing, 70-year-old, unflinching former Communist ideologue, a native of the Carpathian Mountain region of Bukovina (now in Ukraine) and veteran of the Red Army. Ernst, living all alone in Israel and haunted by recurring dreams and thoughts of his eventful past, is counting down the days of his tumultuous but ultimately wasted life. He is a writer who can no longer write. He cannot reach into himself to find the memories and emotions that his harsh experiences have seemingly buried into locked and impenetrably dark places in his soul.

Until he meets Irena.

Irena, a single 36-year-old who lives alone in the home of her deceased survivor parents, becomes Ernst’s caregiver. Shy, self-effacing, self-doubting, yet thoughtful and tender, Irena is totally – even fiercely – dedicated to healing and protecting Ernst from the ravages of his mostly self-inflicted distress. Irena’s daily, tireless ministrations to Ernst become the balm that soothes his wounds and “the key” that has opened “the heavy doors” of his heart.

Appelfeld is unrivalled in his ability to create an engaging narrative with spare, unembellished, economical writing. He is unique in building gravitas and literary momentum slowly, steadily, as if in slow march, through the use of short chapters and finely honed, almost clipped language. Indeed, in an interview with Eleanor Wachtel of CBC, Appelfeld explained his signature manner of writing as stemming from his experiences hiding from the Nazis where language could betray as well as redeem.

True to Appelfeld’s long-perfected purpose, Suddenly, Love implores the reader, despite tears, to see with clarity and empathy the world that the author left behind.

Agnon and Appelfeld were born not very far from each other in what is now Ukraine – Agnon in Buczacz, Appelfeld in Czernovitz. Jewish life in their region was in some sense the epicentre of Jewish civilization in eastern Europe before World War II. That civilization, as we know, alas, was utterly destroyed.

Agnon and Appelfeld are the two pre-eminent Israeli authors whose works are devoted to memorializing that civilization. They do so with a near sacred emphasis on preserving individual and collective memories, and a constant reverence for the vanished people who reside there.