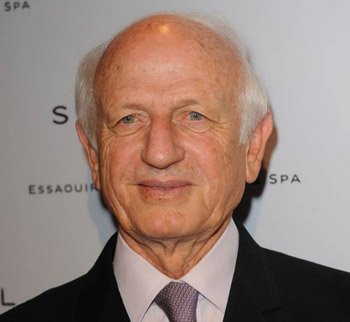

TORONTO — Andre Azoulay is a bridge builder par excellence.

For years now, he has devoted himself to building coexistence and understanding between the Arab world and Diaspora Jewish communities and fostering dialogue between Islam and western societies.

“It is my mission in life,” he said in an interview last week.

Azoulay, a Moroccan Jew, is a senior adviser to King Mohammed VI of Morocco, a pro-western North African Muslim country that has worked for Arab-Israeli reconciliation and peace.

Azoulay was here as a guest of the newly formed Communaute Juive Marocaine de Toronto, an organization that promotes Moroccan Jewish culture and history. Headed by Simon Keslassy, the CJMT was the sponsor of “2,000 Years of Jewish Life in Morocco,” a recent eight-day celebration of the Jewish experience there.

The event, mainly sponsored by UJA Federation of Greater Toronto, the Canadian Sephardic Federation and the Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Center for Holocaust Studies, coincided with the 50th anniversary of Canada-Morocco diplomatic relations.

Azoulay, who was born in the Moroccan town of Essaouira-Mogador in 1941, studied economics, journalism and international relations in Paris. From 1968 to 1990, he was employed by the Paribas Bank in Paris in an executive position.

During the last eight years of the reign of King Hassan II of Morocco, Azoulay was one of his advisers.

With his death in 1999, his successor, Mohammed VI – who has called the Holocaust “one of the most tragic chapters of modern history” –reappointed Azoulay, who advises the royal court on economic affairs and plays a role in encouraging foreign investment in Morocco.

By his own reckoning, he is the king’s sole Jewish adviser, and the only Jew in the Arab world who fulfils such a function.

Azoulay is president of the executive committee of the Foundation of Three Cultures and Three Religions, based in Seville, and one of the founders of the Aladdin Project, with headquarters in Paris.

He is also president of the Anna Lindh Euro-Mediterranean Foundation and a member of the Alliance of Civilizations, a United Nations body created at the suggestion of Spain and Turkey.

Asked what these organizations have achieved, Azoulay would only say that time will tell. As he put it, “It’s a long process, not an easy one, a long way. It needs time, commitment and loyalty.”

He rejected the idea that the Islamic world and the West are on a collision course in a clash of civilizations.

“It’s a theory we have to resist,” he said in French-accented English, noting that religion and politics should not be conflated.

There is, however, a “clash of ignorance.” He said, “We know a lot about western civilization in the Arab world. But what do westerners know about my [Arab] traditions? We have to fill this gap with education.”

In a reference to the Arab world’s golden era centuries ago, he observed, “My region was exporting mathematics and poetry when westerners were breaking stones.”

Decrying the stigmatization of Islam, Azoulay said that Islamophobia and antisemitism are cut from the same cloth of racism. “To resist antisemitism, you have to fight Islamophobia.”

When asked what accounts for Islamophobia, he replied, “I don’t know. We need pages and books to explain this phenomenon. Globally, we’ve regressed. This issue didn’t exist 30 or 40 years ago.”

He claimed that the events of 9/11 were not a factor in sparking or exacerbating Islamophobia.

Turning to the Arab-Israeli conflict, Azoulay said a two-state solution is necessary to defuse Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians. “We’ve missed many opportunities for peace. Justice, dignity and freedom should be the basis of a solution.”

Claiming that peace is possible, despite setbacks in the diplomatic process, Azoulay said, “It’s vital to have a Palestinian state, for the region and the whole world community.”

Morocco has “done all it can” to promote peace, he said in an allusion to the late King Hassan II’s behind-the-scenes role in fostering a rapprochement between Israel and Egypt in the late 1970s.

Azoulay, a resident of Rabat who described himself as “a Berber, Arab and Jew” in terms of identity, claimed that close to one million Jews of Moroccan ancestry, primarily in Israel, France and Canada, consider Morocco their “mother country” with respect to history, culture and cuisine.

“They are Moroccan ambassadors,” he said. “Moroccan Judaism is a happy story.”

In his estimation, Morocco, populated by about 260,000 Jews in 1948, is home to 3,000 to 5,000 Jews today. Asked whether there will be a Jewish community in Morocco in another generation, he said, “I hope so.”

Morocco has weathered the Arab Spring of national rebellions thanks to its status as a constitutional monarchy with a multi-party political system and a free market economy, he said.

“Morocco didn’t wait for any Arab Spring. We’ve made deep structural reforms. I don’t remember one year when we didn’t change something. We’re engaged in a culture of change. That’s why we’re different than other Arab countries.”