MONTREAL – Leading a discussion on whether Montreal’s sole Reconstructionist synagogue should allow interfaith weddings is one of the first and thorniest tasks Rabbi Boris Dolin expects to undertake in his inaugural year as spiritual leader of Congregation Dorshei Emet.

Rabbi Dolin, 38, an Oregon native, officially assumed the pulpit of the approximately 500-member congregation in Hampstead this summer, a little earlier than the July 1 date he was expected to start.

The reason was the sudden death of Rabbi Ron Aigen in May, just weeks before his scheduled retirement after 40 years in Dorshei Emet’s pulpit.

Rabbi Dolin, who was selected from among 28 applicants, is only the second rabbi hired at Dorshei Emet, the oldest Reconstructionist congregation in Canada, founded in 1960 by Rabbi Lavy Becker.

He spent the previous year leading an unaffiliated progressive congregation in Warsaw, after serving four years as associate rabbi of Temple Beth Israel in Eugene, Ore.

Rabbi Dolin positions himself on the more traditional wing of the Reconstructionist movement, which he feels makes him a good fit for Dorshei Emet.

However, he has officiated at interfaith weddings and makes the case that such marriages can be beneficial to the Jewish community, even when no commitment to later conversion is made by the non-Jewish partner.

“Dorshei Emet is one of the few, if not the only congregation in the movement where interfaith weddings are not done,” he noted, also saying that he will accept whatever decision the congregation makes.

Rabbi Dolin’s experience has been that non-Jews marrying Jews are secular or non-believers in their Christian heritage. If he had been approached by someone fully practising another religion, Rabbi Dolin said he would not perform their wedding to a Jew.

The condition he has placed is that the non-Jewish partner promises to “support” Judaism and their spouse’s identification with the faith – and to raise a Jewish family.

Dorshei Emet currently welcomes interfaith families into its midst, he said, although he was not sure if they are extended full membership.

Bringing such non-Jewish spouses into the fold can be good for Judaism, he thinks, as they often carry “less baggage” and lend a freshness to Jewish life that born Jews sometimes do not.

In Poland, his congregants were largely those who only had remote Jewish ancestry or had converted.

Rabbi Dolin is married to Buffalo, N.Y., native Sarah and they have three children.

He does not support Reconstructionism’s controversial new policy of accepting rabbis married outside the faith.

The issue has split Reconstructionists since the decision was made last September. A few rabbis have left the already tiny movement and some congregations are considering their future.

Rabbi Dolin said he remains a “devout” Reconstructionist, but cannot abide its rabbis being intermarried because he thinks they should serve as “role models.”

On this point, he is completely in line with Dorshei Emet’s position – which was unequivocally articulated by the late Rabbi Aigen.

“This is a line we cannot cross,” said Rabbi Dolin, who hews to the vision of Reconstructionism’s founder, Mordecai Kaplan, who was an Orthodox rabbi. He believed “above all” that the movement’s aim was the strengthening of “Jewish peoplehood,” Rabbi Dolin said.

Dorshei Emet, like other Reconstructionist congregations, extends full equality to women and to LGBT people. Same-sex marriages are performed.

Rabbi Dolin is strongly in favour of full marital rights for gays and lesbians and, in fact, officiated at the first Jewish sanctification of a same-sex union in Oregon before such marriages became legal in the state two years ago.

“Everyone who comes into [Dorshei Emet] should walk out a stronger Jew, but they should not have to give up who they are or how they are connected to the world,” he said.

On Israel, he describes himself as a centrist.

One of the attractions of relocating to Montreal was its Jewish community’s strong attachment to its culture and history, he said

He considers himself close to the Conservative movement. He earned a master’s degree in Jewish education at the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary.

Rabbi Dolin came from a not especially religious family, spending the first 10 years of his life in a small coastal Oregon town, before the family moved to Portland, where they joined a Reform congregation.

He had never heard of Reconstructionism until he entered the University of Oregon. He became attracted to its retention of many of the age-old practices of Judaism, such as Hebrew prayer, while adhering to contemporary values, such as equality.

While he loves synagogue tradition, Rabbi Dolin enjoys creating unconventional experiences of Judaism. He plays guitar at Shabbat services, for example.

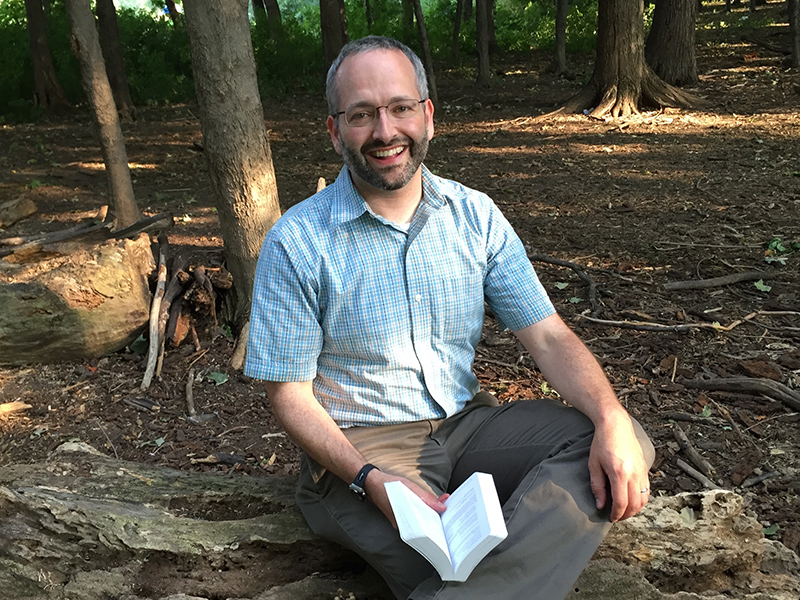

He is an enthusiastic advocate of getting beyond the shul walls and “out in the real world” to pray and learn. His “holy hikes” were popular in the Oregon forests, and he is hoping to start them in Montreal.

He is also experimenting with offering Jewish chanting at a yoga studio and Friday night programming for young adults in Mile End that will appeal to those not comfortable with regular synagogue services.