Dr. Joe Greenberg says there was nothing quite like celebrating the High Holidays when College Street was the heart of Jewish life in Toronto.

The community was centred around College from the mid-1920s until the ’50s, when Jewish families, shuls, schools and businesses migrated north along the Bathurst Street corridor.

Greenberg, 94, is now retired, but he practised family medicine and raised his children just blocks away from his childhood home on Major Street.

He said he never left the neighbourhood, because it was a wonderful place to live. “Why would I want to live anywhere else?”

That was particularly true when the area was “wall-to-wall Jewish,” he said. “Yontif night was incredible.

“On erev yontif, you would walk along College to meet all your friends. We all had new clothes and new shoes… My sister, Rose, worked at Tip Top Tailors. She made up a suit for me.

“We would walk from Major to Grace [Street], greeting every kid we knew. It was such a great feeling to walk along the street and shake hands with everyone… People really knew each other, not like today.”

READ: FAGAN PROVIDES A LOVING PORTRAIT OF 1930S TORONTO

Longtime caterer Sonny Langer, 85, who is also known as Toronto’s shivah king, grew up on Roxton Avenue, in an area now referred to as Little Italy. He remembers standing at the corner of Bathurst and College, where clusters of people gathered after dinner on Rosh Hashanah.

“On the first night of yontif, everybody got dressed up in new clothes. Everyone paraded along College in their new suits. It was a bit of a fashion show,” he said.

“Everyone went to shul first, and then they’d come out onto the street. We talked and hung out. College was known as the hub, so people who lived north in Forest Hill would come down to College Street in their cars,” Langer added.

“People came to look for the girls, and the girls looked for the boys.”

Holy Blossom, the Reform temple, had a shorter service, and the celebration for Rosh Hashanah was only one day, Langer noted.

“The boys [from Forest Hill] would drive up and down College. Some of the girls would hide in the back seats of the cars so they wouldn’t be seen driving on yontif.”

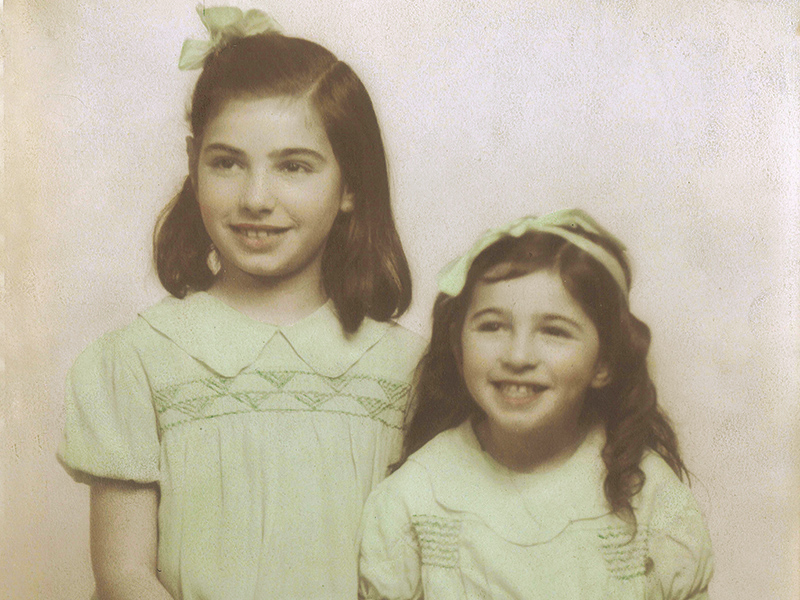

Edith Weinberg, 83, grew up on Palmerston Boulevard. When she and her older sister, Ruth Teitel, 88, were in elementary school, Shirley Temple was very popular and so their mother purchased matching Shirley Temple dresses for the two of them.

“It was a big deal. The dresses had smocking, and we got new shoes.”

She and her sister wore their new Shirley Temple dresses to the Brunswick Shul. At the time, Weinberg was too young to sit through services, so she and the other children played outside of the synagogue.

Like Langer and Greenberg, Weinberg said she also hung out on College Street on Rosh Hashanah when she was a teenager. “We got all dressed up and we walked between Major and Spadina back and forth to see everyone we knew.”

David Pinkus, 92, a longtime Kensington Market resident, said he didn’t go to College Street on Rosh Hashanah, because he didn’t live that close.

However, Pinkus, who was president of the Kiever Shul in Kensington Market for almost 37 years, shared his memories of the synagogue during the High Holidays.

In those says, people were punctual, he said. “Everybody was observant in the 1930s. Everybody was rushing to the shul, so they wouldn’t be late for services.

“It’s not like today. No one came late and nobody left early.”

It was customary for men to get new suits and hats. “Everyone wore fedoras. The women were in their best finery.”

Sometimes the women – they sat in the second-floor balcony – squabbled over the seating, Pinkus recalled. “Some women had permanent seats that they bought. Sometimes some intruder would come in and sit down in a front-row seat [that was not theirs] to get a better view.

“Arguments between the women ensued and the gabbai had to settle these disputes.”

No matter how hot it was outside, the windows in the shul were never opened, Pinkus said. “The cantor [Harry Litvack] was afraid of getting a draft.”

And when the children got restless, they could go outside and play in the park across from the shul.

The women would also often lose interest in the service and many of them would start gossiping up in the gallery, he said. “It would get so loud that service would stop until the women stopped talking.”