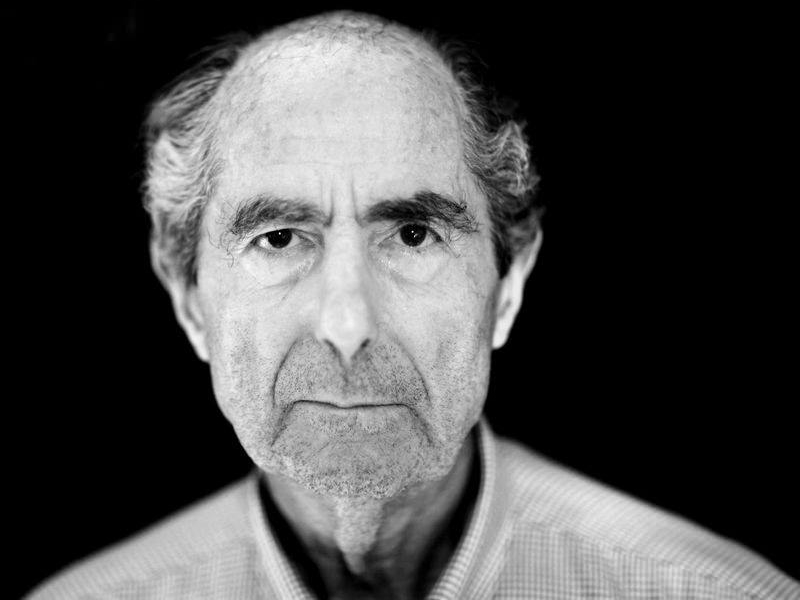

A few weeks back, novelist Salman Rushdie celebrated the career and literary influence of Philip Roth during a speech in the latter’s hometown of Newark, N.J. Roth, Rushdie claimed, “was a writer through whose writing many American moments, past and present, can be explored and understood.”

Two of Roth’s novels stand out to me when considering how the author depicted America’s “big moments.” The first is The Plot Against America, an alternative history of the United States in which Charles Lindbergh defeats Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 1940 presidential election, sending America into a spiral of anti-Semitism. Many were quick to suggest Roth was implicitly criticizing the presidency of George W. Bush, though the author denied it. However, the parallels to the current U.S. president (who back in 2004, when The Plot Against America was published, was quoted as saying, “I probably identify more as a Democrat”) are eerie. Roth’s Lindbergh, like Donald Trump, extols an “America first” ideology, and his election ushers in profound social upheaval and anxiety. For those with a bleak view of President Trump, the novel is particularly foreboding. But The Plot Against America has always read to me as dystopian, rather than a literal warning that it could happen here, too.

By contrast, I Married A Communist, published 20 years ago this month, offers a vivid, tenacious account of McCarthyism. The novel tells the story of Ira Ringold, an American political radical who becomes a popular radio personality known as “Iron Rinn.” Buoyed by his marriage to fellow star Eve Frame, Ringold manages to mask his communist beliefs for a time, until Frame sells him out, leading to his demise.

It’s true that Ringold is partially at fault for his own downfall – as his brother Murray explains, “It’s one thing to have your party allegiance and it’s also one thing to be who you are and not able to restrain yourself. There was no side of himself that he could suppress. Ira lived everything personally … to the hilt, including his contradictions” – but, in the end, there is little he can do to save himself. “To me,” Murray laments, “it seems likely that more acts of personal betrayal were tellingly perpetrated in America in the decade after the war … than in any other period in our history.… It was everywhere during those years, the accessible transgression, the permissible transgression that any American could commit.”

This strain of public attack is increasingly apparent today, when Internet crowds and organized activists routinely call out anyone who does not entirely line up with their way of thinking. They demand ideological purity, shun nuance, and when they don’t get what they want, the knives come out. People are losing their reputations and their jobs for saying the “wrong” thing.

READ: FROM YONI’S DESK: THE LOST DAYS OF TISHREI

Near the end of I Married a Communist, Roth’s narrator reflects: “You control betrayal on one side and you wind up betraying somewhere else. Because it’s not a static system. Because it’s alive. Because everything that lives is in movement. Because purity is petrifaction. Because purity is a lie.” It’s as much an indictment of today’s call-out culture as it is of McCarthyism. The results, I fear, will be similar.