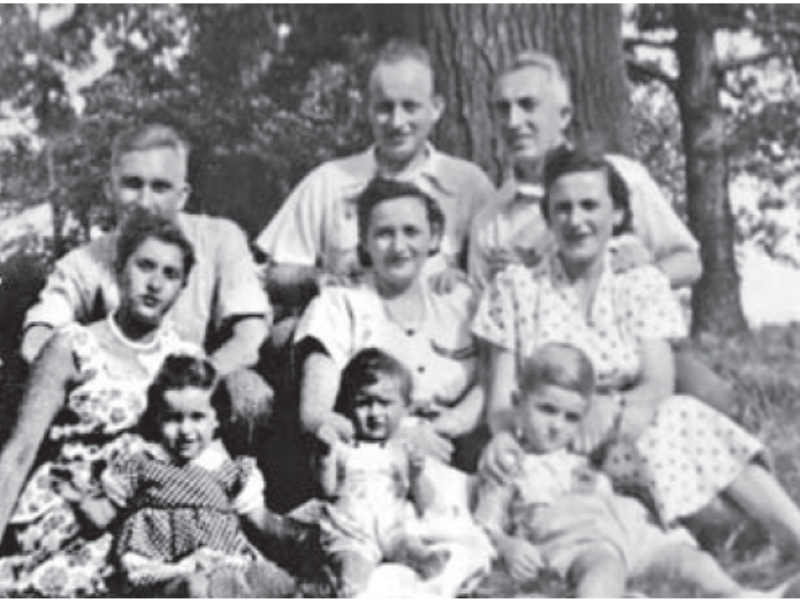

On Sept. 19, 1948, the S.S. Sobieski docked at Pier 21 in Halifax. Among the passengers on the recommissioned cargo ship were my parents, Béla and Judit Rubinstein and my uncle and aunt, Dezso and Vera Rubinstein. Their childless niece and nephew, Kicsi and Sándor Hofstädter, were to follow a week later.

Representatives of the predominantly Jewish Canadian Fur Workers’ Union, which had lobbied the Judeophobic government in Ottawa assiduously, were present to greet the newcomers and accompany them to the train station. They presented a choice of three cities boasting a fur industry: Montreal, Toronto, or Winnipeg. Most of the group got off in Montreal, perhaps in their impatience to put an end to the years of rootlessness. The rest continued on to Toronto. (No one opted for Winnipeg, which was reported to be too cold and remote for human habitation.)

My relatives concluded that it would be difficult enough to learn English, let alone both English and French. And so they decided on Toronto, which sounded rather like “Torino,” the Italian city where they had spent the previous three years in United Nations Displaced Persons Camp No. 17. They eagerly grasped at the flimsiest hint of familiarity in this promising but alien land.

The train carrying the 38 furriers-to-be and their families pulled into Union Station early on Sept. 22. They were greeted by Tobie Taback, secretary of the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society of Canada (JIAS) and some employees of the United Jewish Relief Agencies. Also present was an official from the Canadian Department of Immigration. Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC), working together with JIAS, had made a commitment to the Canadian government to secure housing for the newcomers. The immigration official was present at the train station that morning not so much to welcome the new arrivals to Canada as to ensure that they not set up camp in the manner of “Gypsies.”

The famished travellers were taken to Goldenberg’s Kosher Restaurant for breakfast. Afterward, they were brought to the Labour Lyceum for processing. Once all the paperwork was completed, a CJC employee accompanied each family to its new home. My parents carried me, together with the two knapsacks containing all their earthly possessions, to a dingy two-room apartment in a badly rundown building at 90 McCaul St. Before handing over the key, the chaperone explained that the CJC had already paid the first month’s rent. My father was expected to repay this amount, as well as the cost of the train tickets from Halifax, as soon as he started earning wages.

Inside, the cockroaches were in command, and a single reeking bathroom served all five tenant families. My mother stared at the grimy floor and sobbed quietly. Her first activity in Toronto was to get down on her hands and knees to scrub the floor. She was determined to raise her son with dignity in a clean home, however modest it might be.

Three days later, a Saturday morning, my father and uncle set out in search of their fellow Jews. Spotting a well-dressed gentleman with a velvet bag under his arm, they asked him whether he was going to shul. Yes, he was, and they could follow him if they wished.

But the regulars at the synagogue did not greet the strangers joining them. In a radio broadcast explaining to the Toronto public why it was so important to help the immigrants, an unidentified Jewish community leader quoted the typical complaint: “Why are we going out of our way to do all this for the refugees who have been coming to our community? Did anybody provide me with this help when I arrived here years ago?”

Indeed, when swastikas and anti-Semitic slurs were found one morning daubed on public buildings, many old-timers blamed the greeners for provoking the gentiles with their foreignness.

READ: CAN EDUCATION ALONE SAVE THE JEWISH PEOPLE?

A curious neighbour once asked my mother what had brought her to Canada. She responded matter-of-factly that almost her entire family had been murdered by the Germans during the war. She herself managed to survive Auschwitz and her husband survived Hungarian forced labour camps. It was impossible for them to return home and resume their old lives as if nothing had happened.

A long, awkward silence was followed by a deep sigh and a plaintive lament: “Oy, Mrs. Rubinstein, you can’t imagine how hard it was in Toronto during the Great Depression. We didn’t even have butter to put on our poor children’s bread!” At a loss for words, my mother brought the conversation to an abrupt conclusion. She decided that henceforth, she would keep the memories to herself.

As soon as they had fulfilled their contractual obligation to work for a year as furriers, the entrepreneurial men in my family opened their own small fur shop in Toronto’s garment district. By the mid-’50s, they decided to become builders, undeterred by their lack of money, connections, education, or experience. Together with many other survivor-immigrants, they became part of a uniquely Jewish new industry in Toronto, the construction and management of highrise rental apartment buildings. In the years to come, this industry proved to be a key factor in Toronto’s dramatic evolution into a major metropolis.

And that’s why, 70 years later, amid the controversies raging in a new era of global demographic dislocation, I come down squarely on the side of the immigrants.