Everybody knows that Leonard Cohen is the man. An acclaimed poet, novelist and songwriter, he is Canada’s answer to America’s Bob Dylan.

Cohen’s advancing years should indicate he is well past his prime, but the opposite is true. Like old wine, Cohen gets better with age, at least judging by a concert in Toronto I attended last December. For three hours, he regaled thousands of fans, who burst into applause when he finished one of his signature brooding numbers.

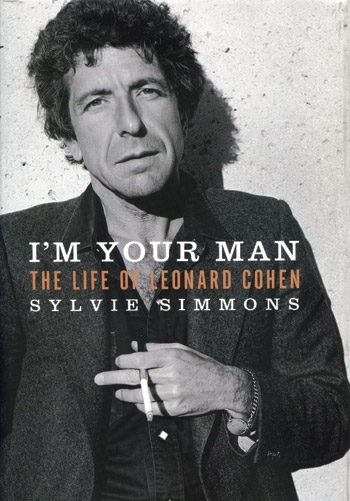

Although Cohen is a public figure, he is a shy, private person. Sylvie Simmons, in I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (McClelland & Stewart), breaks past his façade in a definitive biography.

A music journalist who has closely followed Cohen’s career, Simmons is nothing if not meticulous. Her book is a primer on the importance of excellent research.

She starts with his “privileged” background in Montreal. The scion of a wealthy and accomplished family originally from Lithuania, Cohen was born in 1934 and raised in the lap of luxury in Westmount, a fashionable neighbourhood in the folds of Mount Royal. Cohen’s father, Nathan, was a manufacturer of formal wear. His mother, Masha, was a rabbi’s daughter who spoke Russian and Yiddish.

At Masha’s encouragement, Cohen took piano lessons, only to switch to the clarinet. Along with two McGill University friends, he formed a country-and-western band, The Buckskin Boys, which catered to the then popular square-dancing market.

Cohen was drawn to poetry after reading The Selected Poems of Federico Garcia Lorca. But like some men of his generation, he trafficked in poetry to attract women, having learned that “stories and talk” were an irresistible combination.

In Simmons’ estimation, he became a poet at McGill, his talents honed, in part, by the courses of Louis Dudek. Cohen’s first published collection of poems, Let Us Compare Mythologies, edited by Dudek, brought him to the attention of the media. His second volume of poetry, The Spice-Box of Earth, published five years later in 1961, prompted a Toronto Star reviewer to hail him as “probably the best young poet in English Canada right now.”

Thanks to his foray into poetry, he met Irving Layton, 22 years his senior. They could not have been more different, suggests Simmons. Layton was a brazen self-promoter, while Cohen was modest and self-effacing. Yet the pair maintained a durable friendship until Layton’s death.

Simmons devotes considerable space to Cohen’s sojourn on the Greek island of Hydra, and her focus on it is justified. After visiting Israel for the first time, Cohen discovered Hydra, a haunt of bohemians where he felt at home. There he met Marianne Ihlen, the first love of his life, and wrote his first two novels, The Favourite Game and Beautiful Losers.

Disappointed by their lack of financial success, Cohen talked about becoming a folk music performer and making records. But it was not until 1967, with the Songs of Leonard Cohen, that he finally made his debut.

Curiously enough, he did not like touring. He had a problem with stage fright and feared that his songs would not be appreciated. As Simmons writes, “He wanted to protect them, not parade and pimp them to paying strangers in an artificial intimacy.”

Nonetheless, he flew to Israel to perform for Israeli troops during the Yom Kippur War. His motives were pure. “I’ve never disguised the fact that I’m Jewish, and in any crisis in Israel I would be there. I am committed to the survival of the Jewish people.”

For the next few weeks, Cohen travelled by truck, tank and jeep to entertain soldiers up to eight times a day. And he wrote a song, Lover Lover Lover, in Israel.

Despite his affinity for his Jewish background, he was attracted to Buddhism, a topic Simmons explores at length. Cohen joined the Mount Baldy Zen Center, high in the San Gabriel mountains and some 80 kilometres east of Los Angeles.

He lived austerely in a simple cabin set on the grounds of a monastery, and according to Simmons, he was quite happy performing menial tasks and cooking for and chauffeuring around its spiritual leader.

Cohen likened the Zen Center to a hospital and himself and his fellow residents to “people who have been traumatized, hurt, destroyed and maimed by daily life.”

In 1996, three years into his experience on the monastery, he was ordained a Zen Buddhist monk. But in 1998, he left Mount Baldy, where at times he had found contentment and where he wrote 250 songs and poems in various states of completion.

Cohen prospered as an entertainer, only to find out in 2004 that his longtime manager, Kelley Lynch, had swindled him out of millions of dollars and brought him to the brink of bankruptcy.

As Simmons observes, Cohen was tempted to cut his losses and walk away from the disaster that had befallen him. His lawyers balked, informing him that a lot of the missing money in retirement accounts and charitable trust finds left him liable for crippling tax bills.

Eventually, Cohen recovered some of the stolen funds, but the fiasco prompted him to return to the stage. “Of all the options available to him for making a living, the only one that appeared even remotely feasible was going back on the road,” writes Simmons.

He was 73 when he began to consider the possibility of resurrecting his concert career. Yet he was torn by nagging doubts, fearing he might embarrass himself in front of audiences.

His fears were misplaced. Cohen’s first gig, in Fredericton, N.B., on May 11, 2008, was a resounding success.

More bookings kept coming and again he triumphed, in countries as far-flung as Serbia, Israel and Turkey.

Cohen’s concerts in 2008 and 2009 grossed more than $50 million, and in the process, he earned back all that he had lost.

At this point, he could have retired without too many qualms, she writes. Instead, with his Old Ideas tour, which touched down in Toronto’s Air Canada Centre late last year, he has chosen to enlarge his already considerable fan base and burnish his reputation as a Canadian legend.