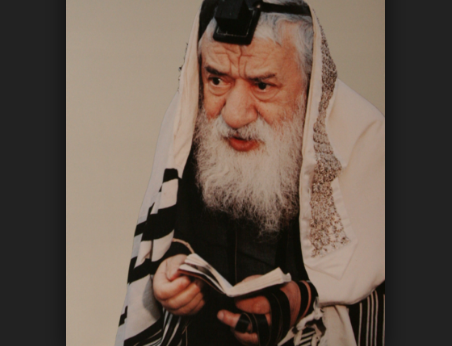

Rabbi Pinchas Hirschprung (1912-1998) was a Torah scholar and chief rabbi of Montreal. In 1944, shortly after he arrived in the city, he published a memoir of his escape from Nazi Europe, Fun Nazishen Yamertal: Zikhroines fun a Palit (From the Nazi Vale of Tears: Memoirs of a Refugee). His account, one of the earliest examples of Holocaust memoirs, was written while the destruction of European Jewry was ongoing and its magnitude still shrouded in the fog of war. (An English translation will be published by the Azrieli Foundation in the fall.)

What was he attempting in his book? Israel Rabinovitch’s introduction characterized Rabbi Hirschprung’s writing style as “temimus,” meaning simplicity, with shadings of innocence and naiveté. Rabinovitch maintained that his narrative was characterized by “fullhearted plainness.”

A.M. Klein’s review essentially agreed with Rabinovitch, asserting that Rabbi Hirschprung wrote “simply” and “without literary frills or esthetic gesturings,” even though he had “a cultured and learned mind.” Rabbi Hirschprung in this sense was clearly presented to the public as a scholar who had never really stepped beyond the limits of the house of study.

However this stands in some tension with the way Rabbi Hirschprung was described by the same A.M. Klein in 1942 when he wrote at length of Rabbi Hirschprung’s mastery of European culture and languages:

“Proficient in the Polish language, with a knowledge of German and as much Latin as Shakespeare had, the culture of Europe has not been foreign to him… The Rabbi had occasion to refer to the writings and doings of such varied worthies as Diogenes, Plato, Spinoza, Heine, Shakespeare, Lessing, and Kant. Of the writings of Freud he has made a special study…”

Rabbi Hirschprung’s stylistic “temimus” thus conceals a complex reality. The “temimus” was perhaps addressed to those in the Jewish community who harboured doubts that the publication of such a narrative was a worthy occupation for a rabbi of his stature.

The discerning reader will also perceive a tension between ideal and reality as Rabbi Hirschprung presents his Polish hometown, Dukla. Dukla was an “ideal shtetl.” Rabbi Hirschprung described its Jews as practically uniform in their Judaic observance. For him, Dukla was, even during weekdays, a town of the Sabbath. That idyllic image clashes with his later descriptions of the Jewish pharmacist who was an assimilationist and of the Jewish barber who gave haircuts behind closed doors on Saturday afternoons.

Quite unexpected is Rabbi Hirschprung’s positive orientation toward communist ideology, even though Soviet suppression of Judaism would have been well known to him. This clearly appears when he writes of his wandering through Soviet-occupied eastern Poland. A group of Red Army soldiers gave him a lift. This incident caused him to recall how as a youngster he thought that there should be a more just political and economic system and read works on socialism. In Soviet-occupied Poland, Rabbi Hirschprung described himself as a “religious communist” who merely wished to be free to observe the commandments of Judaism.

His pro-Soviet attitude must be read in the context of the historical moment in which it was written. The year 1944 was the height of the alliance between the Western democracies and the Soviet Union. The Red Army’s defeat of Germany on the Eastern Front translated into great sympathy for the Soviet Union among Canadian Jews, and into electoral strength for Canadian Jewish Communists and their sympathizers.

Thus, in 1943 Fred Rose was elected to the House of Commons and Joe (J.B.) Salsberg was elected to the Ontario legislature. This historical moment did not last long, for the Cold War would soon drive communists from respectability, but in 1944 the Soviet Union was a heroic ally and its ideology was far from anathema on the Canadian Jewish street.

Rabbi Hirschprung’s evocative memoir of his wanderings in the years 1939-1941 has much to tell us about its historical moment, when Jews had just begun assimilating the enormity of the Nazi destruction of European Jewry and were attempting to search for a vocabulary to describe the Holocaust and a framework in which to place it. In a certain sense, this search began in 1944 with Rabbi Hirschprung’s book. It continues to this day.

Ira Robinson is a professor of religion and chair and director of the Concordia Institute for Canadian Jewish Studies.