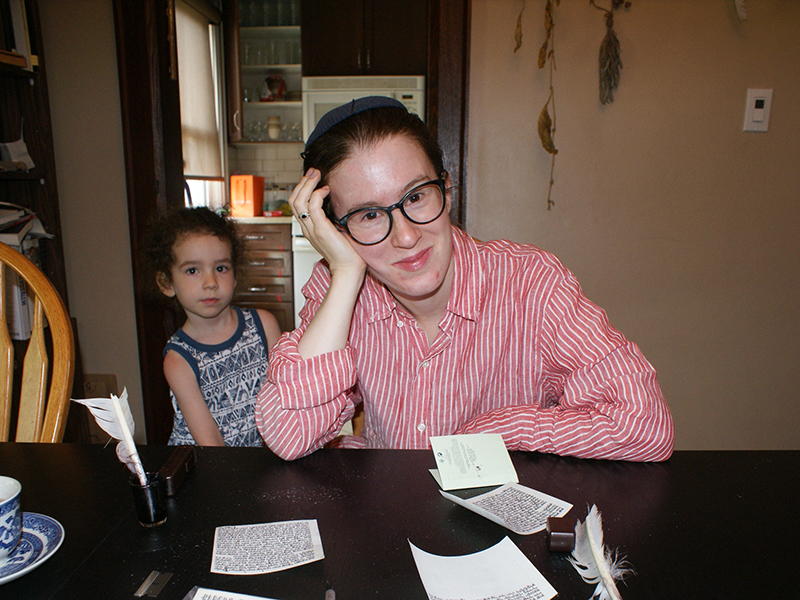

A look of intense concentration has frozen Yonah Lavery-Yisraeli’s face as she focuses on the parchment in front of her. Every stroke of her pen is precise and carefully planned.

Her creation on this day may be only a tiny scroll that will never be seen again once it’s encased in a mezuzah, but it is still a sacred object and thus must be created with reverence.

Lavery-Yisraeli is one of only a handful of women around the world who work as a soferet, the scribes who painstakingly produce the ritual documents of Jewish life – mezuzah inserts, marriage contracts (ketubbot) and even Torah scrolls (soferet is the feminine version of sofer). She is also one of an even smaller group of woman who have written an entire Torah scroll, all 304,805 letters done entirely by hand on parchment made from the skin of a kosher animal.

It’s not a typical avocation for a woman, but “typical” isn’t a word often used to describe how Lavery-Yisraeli fills any of her roles in life – scribe, artist, scholar, rebbetzin, wife, mother and rabbi.

That’s right – in addition to everything else, at 33, she is also an ordained rabbi and teacher of Torah.

She came to Hamilton, Ont., three years ago with her husband, Rabbi Hillel Lavery-Yisraeli, when he took up the pulpit of the city’s Conservative Beth Jacob Synagogue. Technically, that makes her the congregation’s rebbetzin, but “it’s not a role I in any way struggle with, engage with or negotiate with. It’s not part of my life any more than it is part of Hillel’s life (since he is also married to a rabbi). Besides, I’m truly not much of a cook,” she says.

READ: TORONTO REFORM SYNAGOGUE CELEBRATES 60 YEARS

The work of soferet is more to her liking. Her introduction to the craft started when one of her instructors at the Jerusalem yeshiva where she studied noticed her meticulous handwriting and became one of her first mentors. Another important influence was Montrealer Jen Taylor Friedman, who’s generally acknowledged as one of the first women to ever write a complete Torah scroll.

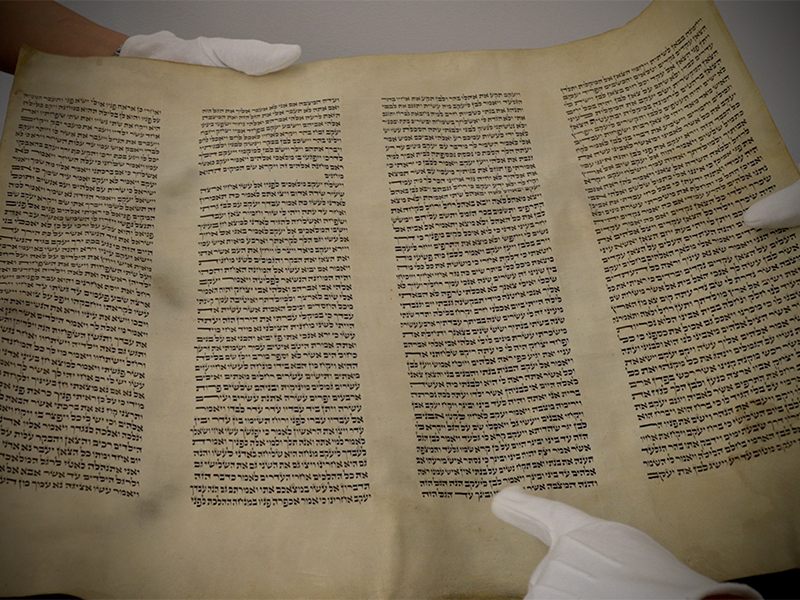

It was Taylor Friedman, in fact, who connected Lavery-Yisraeli with the small Madison, Wis., congregation that commissioned the Torah she completed in 2015. Congregation Shaarei Shamayim and its 130 families had first approached Taylor Friedman about the $45,000 project, but found that they couldn’t afford her. She recommended Lavery-Yisraeli, who, since it would be her first commission, was closer to the congregation’s budget.

She was 29 at the time and living in Gothenburg, Sweden, where her husband worked as a rabbi. Born in Northern Ireland, she has also lived in Toronto, Saskatoon and Israel, where she met and married her husband.

The Wisconsin Torah project took two years to complete, which is longer than usual, but understandable given that the work was interrupted by something virtually unheard of in the male-dominated craft – a maternity leave for the birth of her son, Hisda. “Having my baby in the middle of it did slow me down a bit,” she says.

Joking aside, producing a Torah is a demanding process. Each line must be fully justified on each side and must contain an equal number of words. It must be written with a feather quill and the ink must be as black as possible. The parchment on which it is written must come from the skin of an animal slaughtered in the kosher way and the scribe must be an observant Jew in good standing in the community.

As a scribe, Lavery-Yisraeli says that she is in demand not just to create Torah scrolls, but to repair and maintain them, as well – something she wishes more congregations would do.

“A Torah is a dynamic object that requires care and more congregations need to realize that,” she says. “We have to learn that they are impermanent.”

Although she has been ordained as a rabbi in her own right, the idea of holding down a pulpit doesn’t interest her. Ordination, she said, was never really her goal – it was a way to get the depth of learning she craved.

“My primary goal was just to learn rather than be ordained,” she says. “I wanted to learn.”

That desire to learn was part of the drive behind another of Lavery-Yisraeli’s recent efforts – a weeklong beit midrash in Hamilton, where a small group spent five days immersed in Jewish philosophy and learning.

The idea was born from weekly study sessions that Lavery-Yisraeli holds with McMaster University religious studies Prof. Dana Hollander. They bemoaned the lack of opportunity for more learning in a co-ed environment, and then decided to do something about it.

“There are many opportunities for that in Jerusalem and New York, but not here,” she says. “We decided to turn a sense of complaint into a sense of action.”

The school, held late in August, is a pilot project that may lead to bigger efforts in the future.