The moment I stepped out of the car, I realized that this was most likely the first time a member of my family had set foot in our ancestral town in more than 130 years.

I was in Konin, in the Lodz district of Poland, the town where my paternal ancestors had lived for generations until 1886, when they emigrated to London, England. Family members, including my great-grandfather, later moved to New York and Toronto.

Although there’s nothing extraordinary about the shtetl, Konin was the subject of the bestselling book, Konin: A Quest, by Theo Richmond, which details his journey to find out about the ghetto that his parents had come from.

Richmond’s forebears, like my own, had been fortunate enough to leave before the Nazi slaughtered most of Poland’s Jews. Konin’s population of about 6,000 Jews were deported to various labour camps and sites in the forest, where they were murdered. Only 46 reportedly survived.

Surprisingly, Konin’s main synagogue is still standing. After showing me the market square, my guide led me to this impressive architectural relic from another century. A plaque relates that it had served as the town’s main beit knesset for more than a century, from 1832 to 1939.

Built in a potpourri of styles that includes Moorish and classical Greek, the white stone building was locked and surrounded by overgrown bushes. It was in somewhat of a dilapidated state and its grounds were being used as a parking lot. I remembered seeing a drawing of its elevated bimah in the Konin yizkor book and imagined I saw the dim silhouette of that same bimah through the dirty and darkened windows. Apparently, the building had been recently purchased by a veterinarian who plans to transform it into an animal hospital.

It was here, inside this once grand synagogue, that my grandfather’s grandparents, Rafael Glicensztejn and Rodesz Hahn, were married in 1846 by the town’s rebbe, R. Hirsz Tsvi Amsterdam. That marriage record, which is handwritten in an antique Polish script, was the first of hundreds of family documents that I retrieved years ago from the microfilmed Jewish records from Konin. They have allowed me to trace back my roots to my fifth great-grandparents, inferentially to the 1750s.

The grounds of the former Jewish cemetery have become a legally protected public park, surrounded by a fence and marked by a plaque, but with no surviving stones. It had been closed because a fierce storm the day before had downed some trees.

My guide had heard that there was a monument to the Jews in the Roman Catholic cemetery. Its hallowed ground had also been disturbed by the storm and numerous tree limbs and fresh rivulets of mud lay strewn across the ground. A few dutiful widows, sons and daughters were cleaning the graves of their loved ones. We asked directions several times and were directed ever deeper into the cemetery.

READ: A BRIEF HISTORY OF MANKIND

Finally, we stood before a large monument adorned with a Star of David, a menorah and inscriptions in English and Polish that read: “Here rest the ashes of Jewish prisoners murdered by the German invaders in a forced labour camp in Konin-Czarkow in 1942 and 1943. Being Jewish was their only fault.… May they find eternal peace.”

Several flat-lying tablets bore the names of about 80 victims, including a few surnames that I recognized from my own extended family tree. According to a date on the monument, it had been installed in 2016, but was evidently preceded by an older adjoining stone that explained in Polish that the Jews were “bestially murdered by the Hitlerite Nazis.”

At the foot of the monument was a poignant message from Pope John Paul II, written in Polish and encased in plastic: “This nation lived with us for generations, arm in arm, on the same land that became its new homeland in exile. Millions of sons and daughters of this nation were given a terrible death. They were crowded into ghettos, then taken to camps and gas chambers, killed only for being sons and daughters of this nation. The murderers killed these innocent victims hoping to desecrate our land, but because of such deaths, our land only became more sanctified.”

My time in Konin was short, only a few hours in all, which is insignificant compared to the century, or centuries, that my ancestors spent there. There are no houses, not even a grave, still standing.

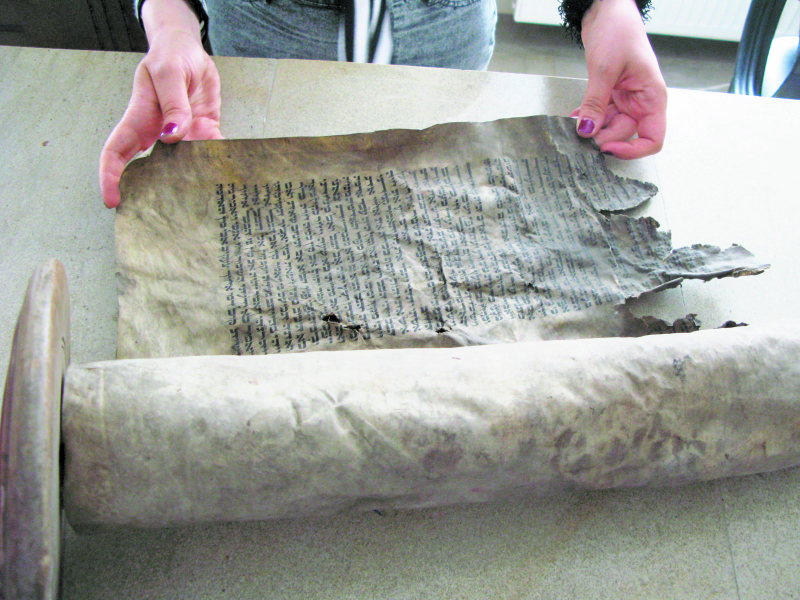

In nearby Turek, we discovered that the town possessed only one relic of its long Jewish past: a portion of a Torah scroll that someone had saved from the synagogue.

The town clerk brought it out to show me. It consisted of four torn and charred panels of Hebrew script, still attached to a wooden spindle, looking exactly as though it had been through devastation and fire. I quickly recognized the segment as being from the beginning of Bereshit. As I explained to the clerk, it told the story of Adam and Eve and the beginning of the world, but I knew in my heart that it also told the story of the end of a world.