“When the war started, we went to Warsaw; later, our father was arrested and we were deported to a forced-labour camp where we harvested timber. Then we were released and found refuge in Iran in the home of a generous Persian Jew.”

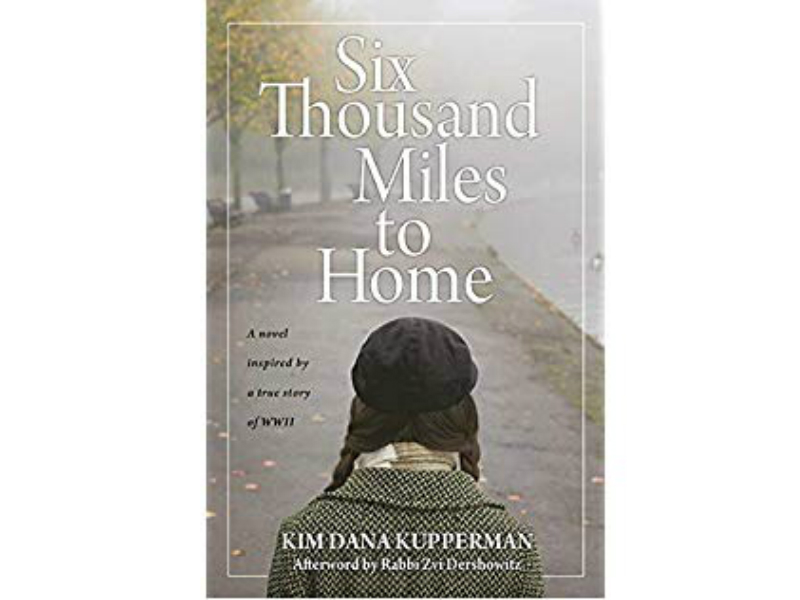

It was from these two bare-bones sentences that Kim Dana Kupperman received her inspiration to write Six Thousand Miles to Home. The speaker is Suzanna Cohen and this is the only surviving statement chronicling her personal tale of trial and triumph during the Second World War. It is Cohen’s story, along with that of her family, which Kupperman skilfully recounts in Six Thousand Miles to Home. Based upon this authentic narrative kernel and extensive subsequent research, Kupperman artfully imagines and reconstructs a fictional account of Suzanna’s family story into an absorbing historical novel.

Because of the actual path of Cohen’s family’s survival during the war, the story focuses on the less chronicled, less well-known subjugation by the Soviet Union of more than one-million Poles, among whom were thousands of Jews. They were brutalized and abused as slave labourers in the vast inhumane maze of the Siberian gulag. The story ends some 6,000 miles away from Cohen’s family’s point of departure in a welcoming, warmer, healing space among the Jews of Tehran.

READ: BOOK EXPLORES CONTENDING VISIONS OF THE JEWISH STATE

Kupperman is an experienced and talented writer, essayist and editor. Her work has appeared in various literary journals, anthologized in Best American Essays and elsewhere, and acclaimed through a number of awards. Her fine writing is on full display in Six Thousand Miles to Home. The prose is clean and clear.

Throughout the novel, the depictions of the family’s various bitter predicaments are powerful and the protagonists’ responses are memorable.

When the Soviet police come in the middle of the night to the tiny apartment in Lviv to arrest Suzanna’s father, she and her brother, Peter, are asleep. Kupperman tightly describes this sudden, nightmarish but not altogether unexpected moment of terror. She then conveys their mother’s dazed reaction in the numb aftermath.

“At the sight of her husband’s rucksack, Josefina felt faint and she sat on the edge of the thin mattress. She could still smell Julius’s warmth. She gathered his pillow in her arms and settled into the dip in the mattress where her husband had just been. She pulled the blanket around her. In time she would learn to sleep without him next to her. In time, she would learn to dwell alternately in two states of mind: one overly aware and vigilant, the other muddled and deliberately unemotional. These states of mind were protective and both born of this moment and its utter and unrelenting despair. But tonight Josefina couldn’t understand any of what would come later. Tonight she had only the quickly evaporating scent of her husband and a hollow place in her gut.”

Kupperman masterfully conveys the heartbreak of this life-altering cruelty. Similarly, to lasting effect, she depicts the brutal conditions of slavery and the constant, debilitating degradation in the labour camps. Raw unembellished truth is its own sufficient detail.

Despite the book’s compelling nature, some quibbles of anachronism do arise. For example, once Suzanna’s family arrives in Tehran and encounters a culturally different Jewish community than their own, the author differentiates between Ashkenazim and Mizrachi Jews. While technically accurate, it is not likely that the term “Mizrachi” would have been used in the early 1940s to describe native Middle Eastern Jews. Nor would the characters then have likely spoken of “repairing the world,” a translation of the Hebrew phrase “tikun olam” taken from Jewish liturgy and theology.

“Repairing the world” is terminology much in use in our time particularly to encourage the younger generation of Jews to find an entry point into Judaism’s endlessly inspiring traditions and heritage.

But such quibbles do not detract from the central power of the novel, namely survival of body, mind and spirit through slave labour internment.

Kupperman told an interviewer “conservative estimates suggest that over 2.7 million people died in the Soviet forced labour camps, most of them during the war years. Yet such information is largely absent in public discourse, mainly because it wasn’t until the opening of archives in former Soviet-bloc countries that scholars started to appreciate the breadth and depth of the camp system and its ruthlessness.”

In addition to imparting the dramatic outline of Suzanna Cohen’s story to generations of new readers, Kupperman also clearly intends the younger generations to know the history of that sorrowful time in modern history.

“I feel a generational responsibility to help preserve the memory of what happened during the Second World War,” she told the interviewer. “For now we know only part of the entire story and because so many died without their stories being told or collected, we must try to imagine how they lived and how they perished.”

The enterprise of writing this book resulted from a collaborative effort between Kupperman and Cohen’s children. Legacy Edition Books, the publisher of Six Thousand Miles to Home, is a project of the Suzanna Cohen Legacy Foundation. Proceeds from the sale of the book are intended to support the foundation’s mission “to collect, preserve, publish and teach the life stories of men and women who marshaled exemplary resilience in the face of forced displacement, and to honour the bravery and generosity of those who provided compassion and assistance to refugees, exiles and persecuted peoples.”

Before his brutal arrest by the police, Suzanna’s father asks himself: “What would the world be like if no one were left to remember what happened to others?” Later in the story, toward its conclusion, one of the key characters we meet in Tehran provides the answer: “To keep a name alive is to enact a small repair to the world.”

However anachronistic the use of the term might have been in that specific context, repairing the world is, after all, still the key purpose to all our lives.