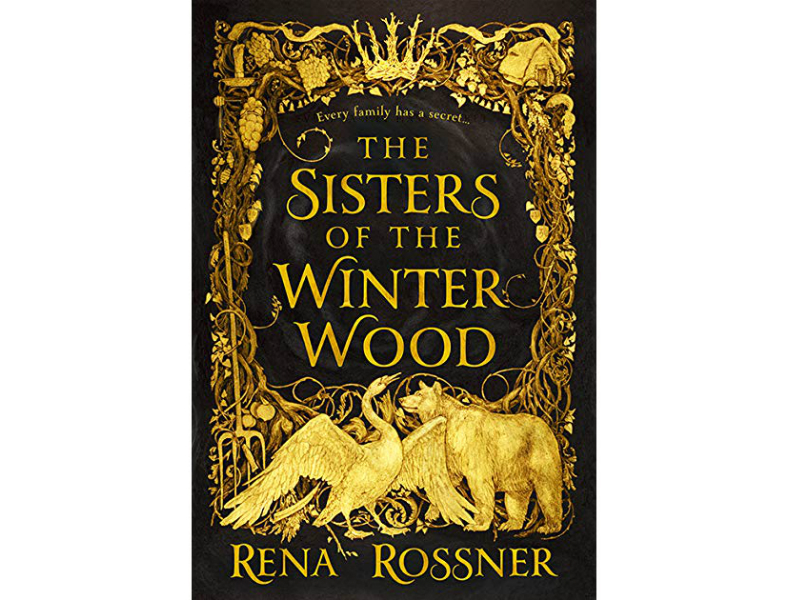

In The Sisters of the Winter Wood, Rena Rossner blends her own family’s history with Russian and Jewish fairy tales, mythology and folklore.

Set in Dubossary, Ukraine, sometime in the early 1900s, the novel tells the story of two teenage sisters, polar opposite from one another, left to fend for themselves after their parents have to leave suddenly.

Liba is 17. She spent a lot of time with her father, a Hasid, and loved listening to him read from the Talmud. “The stories he reads sound like fairy tales to me, about magical places like Babel and Jerusalem,” she says. “And there are learned boys of marriageable age – the kind of boys Tati would like me to marry someday. In my daydreams, they line up at the door, waiting to get a glimpse of me – the learned, pious daughter of the rebbe.”

Laya is 15. She is less concerned with religion and piety, and is more outgoing than Liba. She preferred spending time with her mother, sitting on the deck of the roof, looking at the sky and soaking up the sun. “Mami’s eyes are always looking at the sky,” Liba says. “Laya says she dreams of somewhere other than here. Somewhere far away, like America.”

Laya, like her mother, is also pretty, “thin and full of air,” while Liba describes herself as “different – overweight, not graceful like Laya, not beautiful.”

Rossner chooses to tell the tale from the two girls’ points of view and, as if to stress their differences, Liba’s chapters are written in prose, and Laya’s chapters in verse: “Sometimes I feel/Like my sister and I/Don’t speak the same language/Like we really do come from/Different species entirely.”

Their father was the son of a Hasidic rebbe in the village of Kupel, but their mother was an outsider who had converted to Judaism. The town’s residents shunned her because she didn’t cover her hair, and false rumours were spread that she didn’t keep a kosher kitchen. So they left Kupel and moved to the outskirts of Dubossary, away from prying eyes and constant scrutiny, where Jews and non-Jews got along together.

But one day, two men show up at their door and tell the girls’ father that his own father is dying and he needs to go back to Kupel to pay his respects. Somewhat surprisingly, the girls’ mother also goes along, leaving the sisters alone, but not before warning them that there is danger in the woods around them and that they are to look after each other. The woods, we find out, are enchanted – even haunted, according to some.

The mother also fills the girls in on a secret, one that could be dangerous if the nearby townspeople were to find out.

Shortly after the parents leave, strange things begin to happen. A travelling band of handsome, young fruit sellers settles into town and one of them seduces Laya. Then, when two missing people turn up dead, people start to blame the town’s Jews. The village near the girls’ home becomes dangerous as the local Jews worry about a pogrom. Sensing danger both from within the village and without, the Jewish residents gather together, determined to fight off their enemies.

READ: SOME GREAT READS FOR YOUR HOLIDAY GIFT LIST

The language in the book, particularly Liba’s prose, is rich and descriptive. “All I can think about as we walk are Mrs. Weissman’s varenikes. They are soft and plump and the onions and gribenes she serves them with are always so crispy. Her borscht is thick and creamy and she never skimps on the marrow bones that flavour it. There will be sweet wine, too, and Mami already brought over some of her flakiest rugelach. I lick my lips in anticipation.”

As this passage illustrates, there are a lot of Hebrew and Yiddish words thrown in – perhaps a bit too many. It may not be problematic for readers of this paper, but non-Jewish readers may find it tricky. There is a helpful glossary of terms at the back, though the publishers neglected to highlight its presence, and readers may dive into the story unaware.

The novel also contains a lot of sensuality – perhaps not surprising in a story that at times plays like a young adult coming-of-age tale. This not-so-subtle sensuality is particularly noticeable in Laya’s verses:

“I take an apricot/Out of the bag/While I wait/And bite into its flesh/The juice drips/Down my chin.

“I suck on the fruit/Until my lips are red/Until I’m satisfied … He rubs his thumb/Across my lips/I am transfixed.

“I cannot look away.

“My body thumps/With heat/How can anything/That feels this good/Be bad?”

This is the debut novel for Rossner, a literary agent living in Israel. Her own ancestors narrowly escaped persecution in Dubossary, and she describes the book as her own family’s fairy tale and the outcome of her desire to write a story of Jewish resistance set outside the Holocaust.

She also borrows heavily from Hasidic stories and Russian/Ukrainian fairy tales and myth, and owes a debt to Christina Rossett’s Goblin Market, a 19th-century poem about two sisters tempted by fruit-selling goblins.

At first, the book’s premise is a bit of a stretch. The reader may find it hard to believe that the girls’ mother wouldn’t stay behind with her young daughters while their father goes away. But once you get past that, the book proceeds at a fair pace towards the climax. Sometimes, however, Rossner’s commitment to the two-person prose/verse narrative order leads to redundancy and repetition. But readers who like fantasy and mystical fairy tale books grounded in real historical events will enjoy this book.