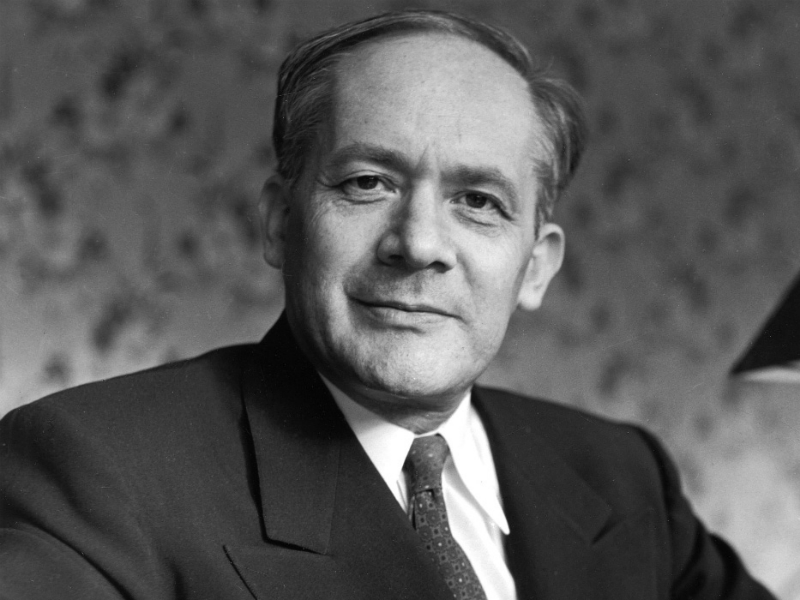

When he was a child, Raphael Lemkin feared exactly three things: needing glasses, losing his hair and becoming a refugee. By September 1939, all three had materialized, as he made his way across eastern Poland to beg his parents to flee before the Nazis arrived.

When they fail to heed his warnings – believing, instead, that no harm would come to Europe’s Jews – Lemkin left his family and made his way to the United States. As a lawyer who was fluent in 13 languages, he became a professor at Duke University and an adviser to the United States Department of War. In his new life in America, Lemkin overcame his fears by dedicating himself to improving the lives of others, culminating in 1944, when he coined the term “genocide.”

Lemkin laid the groundwork for the international community’s anti-genocide laws, which were established with the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Seventy years later, it is fitting that the Jewish community examine and appreciate the unique Jewish roots at the heart of the codification of the crime of genocide.

Lemkin was a unique and quirky individual. Born in eastern Poland in 1900, he grew up amid war and turmoil – with Polish territory constantly changing hands – and became obsessed with death and destruction. He knew that, as a European Jew, he could never let his guard down. Perhaps it was his sense of constant insecurity that gave him his strong belief in the power of the rule of law.

As a law student at the University of Warsaw in the 1920s, he followed the news about the murder of Talaat Pasha, the former Turkish interior minister who was responsible for the massacre of the Armenians, in Berlin. The assassin was Soghomon Tehlirian, a young man who lost his entire family in that massacre. He was on trial for murder for avenging their deaths.

Lemkin asked a professor why someone responsible for a single murder was on trial, whereas an individual responsible for a million murders was walking free. His professor answered that no law existed to try someone for mass murder on such a scale. He compared the massacre of Armenians to a farmer deciding to kill his own chickens. No one could tell him not to do so.

In the 1930s, Lemkin watched the rise of the Nazis and studied their racial policies and laws. He took them at their word about their genocidal intentions. In Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, a definitive work assessing the racial crimes of the Nazis, Lemkin coined the term “genocide,” by which he meant the killing of a group of people.

When the dust of war settled, Lemkin learned that 49 members of his family had fallen victim to the Nazis. He grew ever more determined to have his life’s work adopted by the world, successfully advocating for the new crime of genocide to be included in the Nuremberg Tribunal indictments. Shortly thereafter, he drafted the Genocide Convention, to be considered by the nascent UN.

On Dec. 9, 1948, the Genocide Convention was adopted. Just three years after the end of the Holocaust, the world declared that it would no longer be silent in the face of mass murder. Lemkin did not stop there, working feverishly to ensure that as many countries as possible signed on and committed to preventing genocide.

Lemkin died 11 years later at age 59, while waiting for a bus in New York City. Only seven people attended his funeral and for many years his contribution to the field of genocide studies and international law went unnoticed. Today, Lemkin’s legacy as a human rights lawyer is, thankfully, being revived. His legacy as a proud, defiant and stubborn Jew also deserves recognition. Our community should take great pride in what Lemkin accomplished in his short life, knowing that his strong Jewish roots and identity contributed immensely to the development of human rights in the last 70 years.

READ: ANTHONY: ALL STUDENTS NEED TO LEARN ABOUT GENOCIDE

With a tenacious yiddishe kop, he met with presidents, prime ministers, ambassadors, diplomats and generals, sharing the experience of his people with them. He was a proud nudge and his accomplishments speak for themselves. Today, as we mark the anniversary of Lemkin’s Genocide Convention, let us commit to remember where we come from, take pride in our contributions, expect more of ourselves and demand more of others.