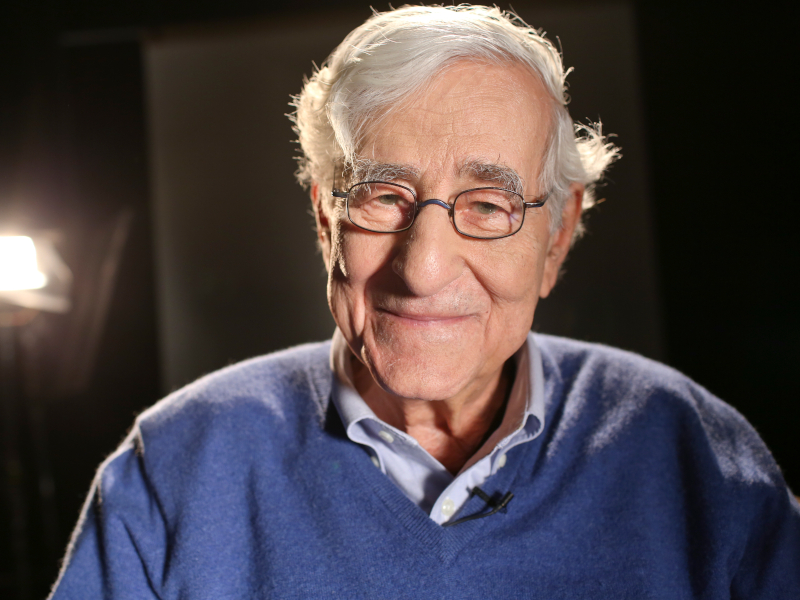

For years, he was a household name in Canada, with a recognizable face and voice to match. Erudite, calm and professional, Joe Schlesinger had an uncanny ability to make sense of chaos.

With his mitteleuropa accent that seemed to delight in rolling the Rs in “Ronald Reagan,” Schlesinger was a consummate reporter for Canada’s national broadcaster. No television newscast was complete without that famous sign-off: “Joe Schlesinger, CBC News, Washington” (or one of a dozen other locations).

Schlesinger, perhaps the best-known among the 1,123 Jewish war orphans brought to Canada after the Second World War, died on Feb. 11 in Toronto, after a long illness. He was 90.

It seemed as though the globetrotting reporter covered it all: Hong Kong, the Indo-Pakistani war of 1971, the 1972 offensive in Vietnam, the ping-pong diplomacy between China and the U.S., the Portuguese revolution, the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. He travelled with U.S. presidents Richard Nixon to China, Gerald Ford to Europe and Jimmy Carter to the Middle East. And he tagged along when Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Tehran from his exile in Paris.

It was, he would understate, “a busy time.”

He was posted to Washington in August 1979, but managed side trips to Vietnam and Afghanistan, following the Soviet invasion.

READ: CBC REPORTER DECRIES ‘NEW’ ANTI-SEMITISM

Schlesinger was born in Vienna in 1928, but his parents, Lilli and Emmanuel, were from Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, and he spent the first 11 years of his life there. As he wrote in Time Zones: A Journalist in the World, his 1990 memoir, “my childhood was dominated by a dark time – the rise of Adolf Hitler – and that forced my eye to begin to see at an early age. Throughout my early years, I watched as the Germans kept getting closer and closer to my family home in Czechoslovakia until, in March 1939, they occupied the country.”

A few weeks before the war broke out, his parents managed to send the young Schlesinger and his younger brother, Ernie, to live in safety with relatives in Britain on the famed Kindertransport. He and his brother bid their parents farewell on June 30, 1939.

Schlesinger returned to Czechoslovakia in the summer of 1945. “It was clear that my parents had not survived the war,” he wrote. They had not been heard from since March 1942, when they had been deported from Slovakia by the Germans and their Slovak allies.

The best information he had was that they were shipped to Lublin, Poland, and that the Slovak Jews who survived the journey were then sent to Auschwitz. “The chances of a middle-aged couple surviving there for nearly three years were nil,” wrote Schlesinger.

In any event, he was laid up in hospital with a bum hip for two years and by the time he got out, the communists had taken over. “I was irrevocably damned because I am a Jew,” he recalled, and by late 1948, it was obvious that it was time to leave.

Instead, he went to Prague, and having learned English in Britain, went to work for the Associated Press, first as a translator and then as a re-write man. It was, he felt, an irresistible calling. “I came to journalism the way an alcoholic may return to bartending or pub-keeping – it gets him close to a regular supply of what he needs most,” Schlesinger wrote in his memoirs. “It wasn’t that I could leave the news alone; it was that the news wouldn’t leave me alone.”

But when the communists began to arrest AP staffers, Schlesinger decided to leave for good and made his way to Vienna. His brother had already come to Canada via the Canadian War Orphans Project, which was started by the Canadian Jewish Congress in 1942. Schlesinger joined him in Vancouver in June 1950.

He worked construction jobs, as a seaman and as a waiter. In 1951, he enrolled in the University of British Columbia to study economics. At some point, he wandered into the student newspaper “and before I knew it, I was editor-in-chief,” Schlesinger told The CJN in a 1985 interview.

He freelanced for the Vancouver Sun, then got a job at the Province. He never graduated.

In 1958, he got married, headed east and did a stint at the Toronto Star. But Europe beckoned. After a year in London working for United Press International, he landed a job in Paris with the Herald Tribune. He returned to Toronto in 1966 and within a few years, became the executive producer of The National.

Yet the desk job did not appeal to him, because, as he put it, “I didn’t like being a bureaucrat dealing with contracts and budgets.” So he returned to his first love – reporting.

He was in the thick of guerrilla wars in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Cambodia. He was in St. Peter’s Square in Rome in 1978 when John Paul II became pope. He accompanied Reagan to Berlin in 1987 to hear the president exhort the Soviets: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

He remembered thinking, “ ‘That’s not very likely to happen very soon.’ And, of course, it did.”

Remarkably, in 1989, he returned to Prague to witness and report on the Velvet Revolution. He said it was the highlight of his career.

Schlesinger was named chief political correspondent for The National in 1991, in time to cover the Meech Lake Accord. He retired three years later, but continued as a special contributor to news programs.

He was awarded the Order of Canada in 1994 and was inducted into the CBC News Hall of Fame in 2016.

“Joe had a formidable intellect and a natural curiosity, which always led to interesting insights in the stories he told,” Jennifer McGuire, general manager and editor-in-chief of CBC News, said in a statement. “He was remarkable – a giant in our profession.”

Esther Enkin, the CBC’s former ombudsperson, recalled preparing to head to Amman on the eve of the first Gulf War. “I didn’t know Joe well and was more than a little intimidated, but I valued his advice and I had some questions. He was so supportive, warm and generous with his knowledge and insight,” she told The CJN.

It wasn’t that I could leave the news alone; it was that the news wouldn’t leave me alone.

– Joe Schlesinger

“Growing up on CBC News, he is intertwined in my mind with some of the most important and dramatic events of the 20th century. What a loss.”

Schlesinger’s parents had been Orthodox Jews, but, as he explained to The CJN, in the German, not the eastern European, tradition. “To us, everyone to the north and east were Litvaks,” he said. And while he knew Czech, Slovak, German, English and French – and had, as he said, an accent in all of them – he did not know Yiddish and did not have a bar mitzvah. The war had cut him off from Judaism.

While living with a family in Yorkshire, England, “one day this rabbi comes along from Leeds and tells people they should feed me kosher meals. They looked at him like he had just come from the moon.”

He conceded that he had found the “preoccupations” of Canadian Jews in the 1950s to be “strange,” as “They were still relating to the Europe of 1910, when they or their parents left czarist Russia.” While he felt culturally Jewish, he described himself as “a Jewish dropout.”

Even so, he helped publicize the story of Sir Nicholas Winton, who had organized the rescue of the 669 mostly Jewish children who were spirited to Britain on the Kindertransport.

He once commented that, “I have a career of wandering around the world, watching the universe and actually getting paid for it. It’s like a little boy’s dream.”

He is survived by his wife, Judith Levene, daughters Léah and Ann, brother Ernie and grandchildren Rachel, Antonia and Noah Salisbury, and Denali Joe Schlesinger.