In our series on Jews behind bars, we have looked at the treatment of Jews in jail, at the organizations and people who try to inject Jewish flavour into the monotonous years in prison, and at Jews observing Passover behind bars.

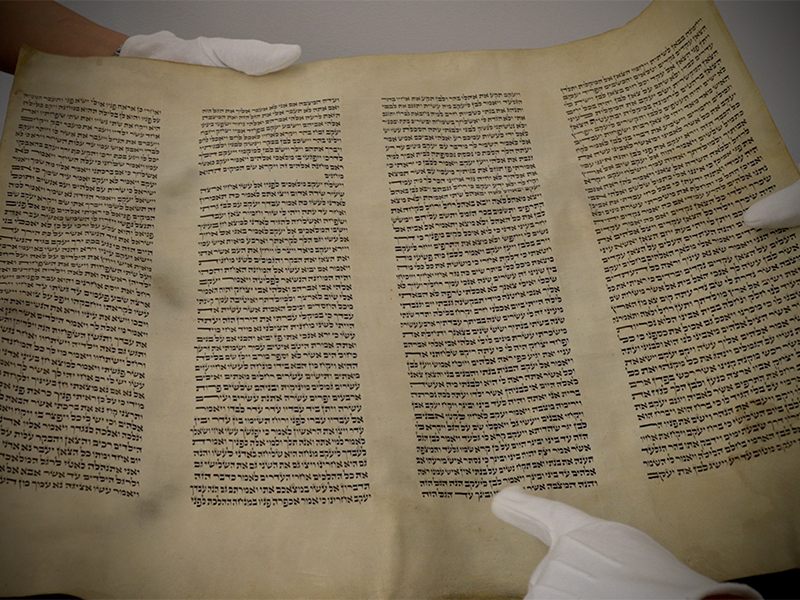

But what does the Torah have to say about incarceration? Quite a lot, actually (although much of it isn’t very complimentary.)

Although the Torah prescribes many punishments including lashes and the death penalty, incarceration was rarely used. Perhaps the most famous person in the Torah to be incarcerated was Joseph who was imprisoned after Potiphar’s wife falsely accused him of trying to violate her. Later, Samson was confined by the Philistines. (Judg. 16:21) In both Joseph and Samson’s cases, the imprisonment was by non-Jewish authorities.

Elsewhere in the Torah, we are told of two other people who were incarcerated. One was a blasphemer (Lev. 24:10) and the other was a man involved in the forbidden activity of gathering wood on Shabbat. (Num. 15:32) As Rabbi Jill Jacobs and Rabbi Jonathan Crane point out, in both cases, the transgressors were placed in “mishmar —temporary custody—until Moses can ask God how to handle them. The closest modern analog seems to be ‘lockup,’ the cell where an arrested person is held until s/he is brought before a judge or released.”

Chabad rabbis in Quebec look out for Jewish prisoners

An excellent article in the Jewish Virtual Library points out that in the Talmudic period, there was an unpleasant type of incarceration used in situations in which the defendant deserved the death penalty, but could not be carried out for technical reasons. Known as hakhnasah la-kippah, (confinement in a “cell”), Maimonides describes “a prison seat that is placed in the prison, only as large as the person’s height, who has no place to lie down or sleep.”

Since then, Jewish courts have used confinement as a tool to compel compliance with its rulings or to deal with contempt of court. However, various halachic rulings dictated that prisoners were to be provided with food, clean quarters, and – separate therefrom – sanitary facilities.

Rabbi Sholom Lipskar writes that the Torah does not view prisons as an approved means of punishment. “The criminal justice system punishments should effect direct results and benefits for all parties involved: the perpetrator, victim and society in general. … Imprisonment does not serve these functions. It certainly brings no benefit (short or long term) to the victim. It appears to offer only temporary benefit to society (taking into account the high percentage of recidivism and the increasing numbers of people being sent ‘away’). And it obviously does no good for the inmate. On the contrary, prison inhibits and limits man’s potential, destroys families and breeds bitterness, anger, insensitivity and eventual recidivism.”

READ: JEWS BEHIND BARS – PART 1

Rabbinical students Peretz Schapiro and Dov Kalmensohn spent a summer travelling from prison to prison visiting Jewish inmates. Before setting off, Schapiro asked the head of their yeshiva what they could share to to lift the spirits of the Jewish prisoners.

He told them that of all the great personalities in the Torah, including the Patriarchs and Moses, only Joseph, while in prison, is called a “successful man.” When things are going right for someone and he enjoys success in what he is doing, it’s not real success, rather the result of circumstance. But when things are not going right and the person still remains positive and focused on his goal, he is a successful person. Joseph, who was hated by his brothers, sold into slavery and thrown into a dungeon for a crime he didn’t commit, had every right to be angry at society and lose focus. However, even after these terrible things had befallen him, he kept a positive outlook and a good attitude.

Another site quotes the Talmud in explaining the importance of this work, “We read in Tractate Berachot: Once when rabbi Chanina became gravely ill, Rabbi Yochanan came by and sat down to visit him. … Rabbi Yochanan remembered that Rabbi Chanina healed someone with the exact same illness. Rabbi Yochanan then said, ‘rabbi, why don’t you heal yourself?’ He responded, ‘Prisoners cannot take themselves out of their own prison.’ Thereupon, rabbi Yochanan got up and healed him.”

What is the Birkat HaGomel? Jewish Blessing for Gratitude

And when the prisoner is finally released, Judaism has a blessing for that. The Gomel is a short prayer of thanksgiving that is recited when is one delivered safely from several life-threatening situations. Although it is more commonly recited after recovering from a serious illness or completion a perilous voyage, the blessing is also recited after release from a dangerous imprisonment. “Boruch atah… hagomel l’chayavim tovot shegmoloni kol tuv” – Blessed are You Hashem King of the Universe, who bestows good things upon the guilty, who has bestowed every goodness upon me.”