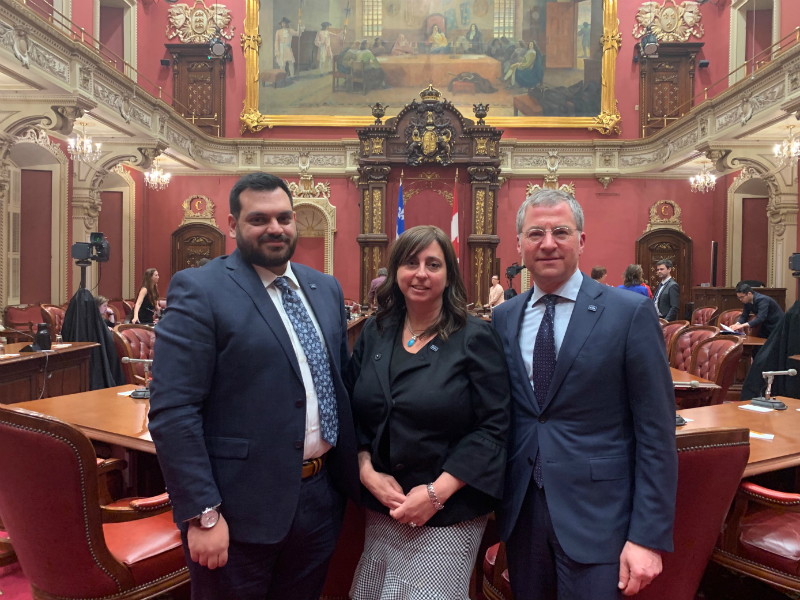

The Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA) reiterated its opposition to Quebec’s proposed state neutrality law at public hearings held at the national assembly in Quebec City on May 7.

While it is against prohibiting any public employee from wearing religious symbols, CIJA believes that, at the very least, teachers in the public school system should not be among those subject to the law.

Unlike police and prison guards, for example, CIJA does not believe a “coherent argument” can be made that teachers represent state authority, as defined by Bill 21.

CIJA’s Quebec vice-president, Eta Yudin, later told The CJN that the organization told the commission that the government has failed to make its case for the bill.

“While maintaining its opposition to any restriction on religious symbols, CIJA noted that the inclusion of teachers in the bill goes even beyond the government’s own rationale for public employees in positions of coercive authority,” she said.

In its written submission to the national assembly, CIJA contends that the religious symbols ban is an infringement of fundamental freedoms that cannot be justified, because official secularism has long since been established in Quebec.

Maintaining state neutrality is “an institutional, not individual, duty,” and there is no evidence that the impartiality of employees wearing religious symbols is affected, CIJA states.

It said that the ban is a “disproportionate attack” on the rights of religious expression and equality of access to employment.

The controversial bill was introduced by the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) government in March.

CIJA argued that removing teachers from the list of employee categories subject to the law “would constitute a judicious compromise and would contribute to increasing the social acceptability of the (bill) beyond the political and identity divisions in our society.”

CIJA argues that teachers are “neither agents of the state nor invested with coercive authority as understood in the case of police officers.”

READ: LEVY: BILL 21 TRAMPLES UPON ALL FOUR PRINCIPLES OF STATE SECULARISM

Most of CIJA’s submission raises concerns about the bill’s ambiguities and imprecision, which it believes will lead to “arbitrary and subjective” implementation of the law and a slew of legal challenges.

First of all, which religious symbols will be outlawed is not defined in the bill. Moreover, too much discretionary power is placed in the hands of the administrators of public institutions, who will be charged with applying the law, according to CIJA. As it is now written, the bill allows for a wide interpretation, which “will pave the way for serious inconsistencies … from one institution to the other.”

CIJA asks how an administrator is supposed to decide what symbol is religious, as opposed to cultural, or just fashionable. For example, would what Jews call “the hand of Miriam” and Arabs call the “hand of Fatima” – to which wearers of the jewelry may assign national, cultural or religious meaning, or simply good luck – be forbidden, CIJA wonders. And what about the Star of David, which it says is a “national symbol” of the Jewish people and not a religious one?

CIJA says a Hasidic man might not only be required to remove his kippah, but other markers of his religion, such as his beard and payot, or even his black frock coat.

The bill does not spell out what would happen in cases of non-compliance, it adds.

“It is essential that the law be amended so that its provisions, enforcement mechanisms and sanctions regime are coherent and comprehensible,” CIJA states.

While the inclusion of a “grandfather” clause protecting current employees is commendable, CIJA warns that this acquired right is lost if the employee is promoted, or their job description changes. It suggests the clause apply to individuals, rather than their function.

CIJA thinks that without major changes, the law will not put an end to the long-running debate about secularism, as the CAQ hopes, but will instead exacerbate the fight.

The “deplorable” inclusion of the notwithstanding clause in the bill to pre-empt constitutional challenges will not stop other types of legal cases against it, CIJA says.

The neutrality of Quebec and its public institutions has been a “political and social reality” since the Quiet Revolution, according to CIJA. “This laicity is already a proven fact, and not an unfinished project as is claimed in certain circles.”

Earlier in the day, Rabbi Avi Finegold, from the multi-denominational Montreal Board of Rabbis, joined representatives of Christian, Muslim and Sikh organizations in decrying the limitations they claim the government placed on public consultation.

The six days that were set aside for testimony from 36 different groups and individuals is not enough, they say. Furthermore, they believe that groups that are critical of the bill were not given the opportunity to speak, while those in favour of it are over-represented at the hearings.

Rabbi Finegold said the government appears to be rushing through the hearings phase, so that it can pass the bill as quickly as possible. Premier François Legault has said that he wants to see the law adopted before the summer recess.

CIJA is one of only two groups representing a specific faith community that were allowed to be heard at the national assembly. The other was from the Muslim community.

Two umbrella organizations with interfaith membership were also given a chance to speak. Among them is Coalition Inclusion Québec, in which rabbis Lisa Grushcow and Michael Whitman are active.