The Toronto Raptors are in the NBA final! They even won the first game against the heavily favoured Golden State Warriors. Dayenu. The Raptors are being celebrated not only for their success on the court, but for the pan-Canadian multicultural nature of their fan base, symbolized by the team’s global ambassador, Canadian-Jewish rapper Drake, and Sikh superfan Nav Bhatia.

Basketball reflects the multicultural character of Toronto. More than hockey, baseball, and football, basketball is an international sport. Like soccer, it is popular everywhere. Unlike soccer, basketball does not have the same association with nationalism we see every four years during the World Cup. Interest in Olympic basketball pales in comparison to college and NBA fandom. The sport has succeeded in becoming international without nationalism. Perhaps this helps explain the special relationship Jews have long had with basketball.

In North American history, sport has served as an effective vehicle for assimilation. In 1923, baseball writer Fred Lieb observed: “Next to the little red school house, there has been no greater agency in bringing our races together than our national game, baseball. Baseball is our real melting pot.” In 1909, The Forward, New York’s pre-eminent Yiddish newspaper, printed an explanation of the rules of baseball, complete with diagrams. The editors understood that this was a path to Americanism. A century later, Punjabi broadcasts of Hockey Night in Canada fulfil a similar function.

Prior to the Second World War, the two most popular sports in the United States were baseball and boxing; basketball did not have a reputation for being a particularly American game. In his 1938 book, A Farewell to Sport, journalist Paul Gallico explained how basketball “appeals to the Hebrew with his Oriental background [because] the game places a premium on an alert, scheming mind and flashy trickiness, artful dodging, and general smart alecness.”

Long before the era of slam dunks and three pointers, Jewish craftiness was thought to offer advantages on the hardwood, but not the baseball or football fields. Gallico’s anti-Semitic assertion highlighted the idea of Jewish distinctiveness. Jews excelled at basketball because they were different, and the tricky game accentuated that difference.

READ: CANADIAN JEWS ARE MORE ACCOMPLISHED AT SPORT THAN YOU’D THINK

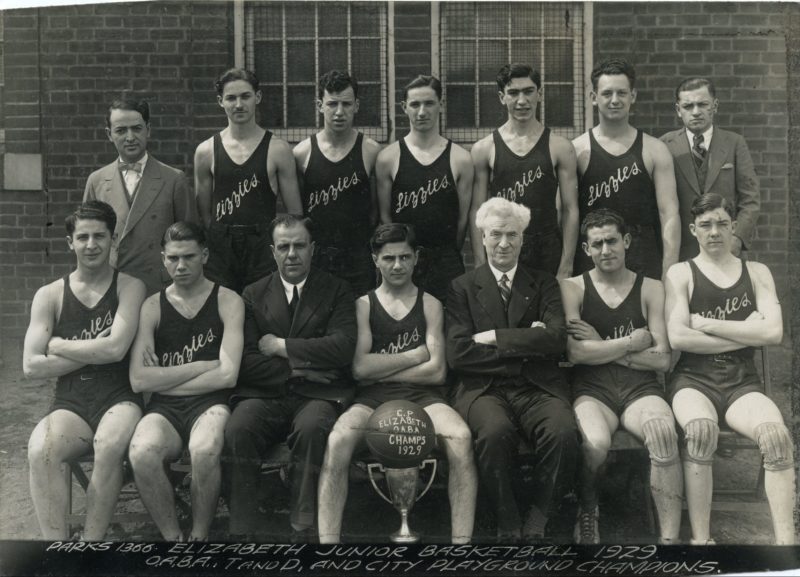

The Jewish relationship to basketball was initially more about participation than spectatorship. Invented in Springfield, Mass. in 1891 by Canadian James Naismith, basketball became popular in the early 20th century in the immigrant settlement houses and Jewish community centres of New York. Talented Jewish hoopsters played for commuter schools like the City College of New York (CCNY) and New York University. Numerous Jews starred in fledgling professional leagues and on independent barnstorming teams, and Young Men’s Hebrew Association teams in Canada and the U.S. won titles in local leagues. In 1950, CCNY won the NCAA championship with a mostly Jewish squad, just as the NBA became America’s dominant professional basketball league.

Postwar economic mobility and suburbanization ended the Jewish basketball era. While some Jewish players achieved professional success in the 1950s and 1960s, the Jewish role in the NBA shifted to coaching, ownership, and the front office.

Yet the Jewish relationship with basketball has persisted. In 1999, Sports Illustrated ran a story about Tamir Goodman, the “Jewish Jordan,” a high school basketball star for Baltimore’s Talmudical Academy. The annual Israel Becker Basketball Invitational tournament, hosted by the Community Hebrew Academy of Toronto (CHAT), attracts Jewish high school teams from across the globe. Modern Orthodox Jews everywhere celebrated when the Yeshiva University basketball team made its first NCAA Division III tournament last year. Jewish participation in varsity basketball continues, and Jewish NBA fandom only grows.

And so Canadian Jewish basketball fans, from Vancouver to Montreal, are rooting for the Raptors. They join fans black and white and brown, Asian and First Nations, anglophone and francophone, Muslim, Christian, Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, atheist, straight and LGBTQ and everyone in between. They all feel a claim to the “we” in “We the North.” There’s nothing smart alecky about that.