Rothenburg ob der Tauber was a last-minute addition to our itinerary on our trip to Germany. After spending several days in urban areas, we thought it would be advantageous to investigate a few countryside options. Almost every story I read about day trips originating in Frankfurt featured this picturesque medieval town where “history comes to life.” I shared some of the online images with my husband. To say we were intrigued was an understatement.

We looked forward to driving through one of the fairytale-like entryways to this famous walled city with narrow cobblestone streets lined with half-timbered houses with red-tiled roofs. I couldn’t wait to be transported back to the Middle Ages, and my husband was amenable to my wish.

If time allowed, we could check out a local bakery item called a snowball, visit the Medieval Crime and Justice Museum, admire the architecture inside the wall and participate in the Night Watchmen’s Tour in the evening, which gives a good overview of the local history.

Even though we are well versed on the restrictions placed on Jewish communities during the Middle Ages – as well as the relentless persecutions, arsons, extortions and violent attacks – we didn’t anticipate finding any notable efforts to keep Jewish history alive in the German countryside. To our complete surprise, the town did not attempt to conceal its less-than-stellar past. Instead, self-guided walking tour booklets written by Oliver Gussmann, the pastor at the St. James church, are available for visitors to piece together Rothenburg’s unsettling Jewish past, while posted signs memorialize each historic site along the route.

Before our arrival, Robert Nehr, from the Rothenburg Tourismus Service, became aware of my extensive background in Jewish studies and graciously arranged for my husband and I to be guided by a local expert on Jewish history, Lothar Schmidt.

Kapellenplatz (Chapel Square): the site of the first Jewish quarter (ca., 1180-1350)

We followed Schmidt and Nehr to a small town square, Kapellenplatz, with two rows of parked cars in the middle of the cobblestoned area that’s surrounded by buildings. We stopped in front of a building with a sign acknowledging the presence of the first Jewish quarter. This small Jewish community, which comprised approximately 10 per cent of the town’s population, lived just inside the town gate and had a synagogue, school, community hall, mikveh and a cemetery.

Historical documents reveal that members of this community held many professions, including educators, bakers, doctors, butchers and moneylenders. Under the reign of Rudolf I of Hapsburg (1273-1291), the Jews were forced to pay a more significant tax to the emperor, instead of paying a smaller fee to the region’s noblemen. Many Jews chose to relocate, to avoid this excessive monetary burden.

In subsequent years, Jews were accused of ritual murder, assaulted during the Rintfleisch Pogrom in 1298 and endured numerous violent attacks between 1336 and 1342. A small monument near the Blasius Chapel in the Castle Garden memorializes the Rintfleisch Pogrom and the memory of the 450 Jews who took refuge in the imperial castle and were burned alive by their Christian neighbours. During the Black Death of 1349, the Jewish community was destroyed once again, and records indicate that it was totally eliminated when Emperor Charles IV gave the Jewish residences to the town in 1350.

A nearby sign on the wall of Kapellenplatz No. 5 recalls the life of Rabbi Meir ben Baruch (ca., 1215-1293). He was taught by some of France’s most erudite rabbis and, in the mid- 13th century, witnessed the mass burning of Jewish texts in Paris. He is considered to be one of the last great Tosaphists of Rashi’s commentaries on the Talmud and a liturgical poet whose poems were included in medieval German machzorim.

From 1246-1286, Rabbi Meir’s school in Rothenburg attracted Jewish students who recognized his exemplary scholarship. His influence extended well beyond the German-speaking part of the world. From Rothenburg, and later from a prison cell in the fortress of Ensisheim in Upper Alsace, Rabbi Meir issued responsa, answering pertinent questions about civil and criminal law issues. A collection of Rabbi Meir’s responsa has been preserved to this day.

The exact circumstances surrounding his imprisonment and death remain unsubstantiated. Schmidt recounted one of the prominent theories that Rabbi Meir’s unsuccessful attempts to free himself, along with a group of other Jews, from King Rudolf’s grip led to his capture and imprisonment. Accordingly, Rabbi Meir died in his prison cell because he put the financial security of his community above his own life, when the Jewish community was asked to pay a hefty ransom for his release, which Rabbi Meir chose not to do.

Rabbi Meir Garden and the Judentanzhaus

A short distance away, we stood near the location of the 15th-century Jewish community centre, which was destroyed during the Second World War, when nearly half of the town was damaged by targeted bombings. In the adjacent garden, a plaque recalls the expulsion and murder of the Jews from 1933-38. Embedded into the perimeter wall are 10 14th-century Jewish gravestones from the burial ground referred to as Schrannenplatz, which was originally known as Judenkirchhof. Later on, Schmidt led us to a parking lot where the cemetery once stood.

READ: FRANKFURT – THE PAST AND THE PRESENT

Judengasse: the site of the second Jewish quarter

“The Jews’ Alley” was established in 1371 on a former city moat in the northern section of the city. We followed Schmidt and Nehr along a narrow, slightly winding cobblestone street, where Jews once lived in simple houses.

They both pointed to more than a dozen former Jewish homes built in the 15th and 16th centuries. Luckily, these structures survived the war and are undergoing various stages of renovation. According to a sign, “it is the only medieval quarter still remaining within the boundaries of German-speaking countries.” Unlike other parts of Europe, where the Jews were forced into ghettos, the Rothenburg Jews lived amongst their Christian neighbours.

In front of one house, Schmidt described the work that is being organized by Kulturerbe Bayern to preserve a two-metre deep mikveh in a vaulted basement within a narrow two-storey building. Many experts believe that this early 15th-century ritual bath is the oldest in Germany. Nehr and Schmidt both anticipate a 2021 opening date. Today, what remains of this Jewish neighbourhood is a modest stone plaque embedded into the wall of a structure. The cemetery has been replaced by a parking lot.

In the early 16th century, it was typical for southern cities in Germany to expel their Jews. From 1520 to 1870, Jews did not reside in Rothenburg.

Nineteenth and 20th centuries

The resettling of Jews in Rothenburg coincided with the 1871 declaration that Jews and Christians were equal citizens. By 1910, the Jewish community had grown to approximately 100 members and was supported by numerous communal organizations. We walked to 21 Herrngasse, so we could see the former location of the Israelite Congregation.

Germany was filled with anti-Semitic propaganda throughout the 1920s and some of Rothenburg’s residents were at the forefront of attacking their Jewish neighbours. By 1933, only a few dozen Jews remained.

When the National Socialists came to power, the majority of the remaining Jews heeded the warnings and moved elsewhere.

On Oct. 22, 1938, two weeks before Kristallnacht, the Nazis rounded up the last 17 Jews and expelled them.

Stolpersteine or stumbling blocks

In Frankfurt, our guide had pointed out the controversial plaques in the sidewalk that memorialize victims of the Holocaust. During our tour, we saw two along our path. When asked if Schmidt knew how many there were in Rothenburg, he simply responded, “About 10.”

Rothenburg museum

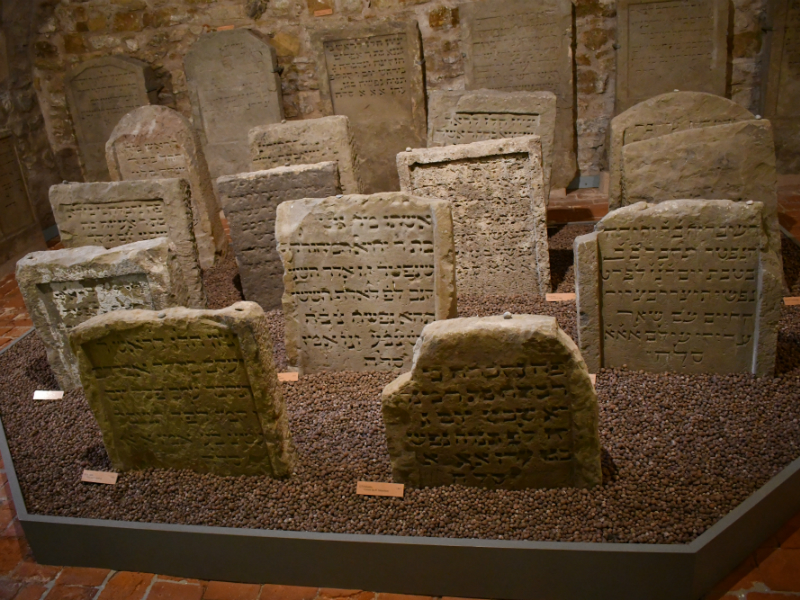

Even though it was closed at the time, Nehr arranged for a private visit to the museum, which is housed in a former medieval Dominican convent. Our brief tour was of the small Judaic collection, which was created in 1993 to commemorate Rabbi Meir’s 700th birthday. We viewed a selection of ritual and ceremonial objects and a grouping of engraved 13th- and 14th-century headstones from the Judenkirchhof. These burial stones, along with the ones mounted in Rabbi Meir Garden, were uncovered in the early part of the 20th century. Disappointingly, the explanatory signage was all in German.

Cemetery at Wiesenstrasse

Nehr helped us locate a Jewish burial ground, which dates back to 1875, outside the town’s walls. Without a key to the locked door, we glanced through an iron gate decorated with a Star of David. A high white wall protected this small plot of land in a residential neighbourhood. Fading Hebrew and German words on grey headstones outlined the resting places of 46 Jews.

Preserving Rothenburg’s Jewish history

If Nehr had simply honoured my request to see a sampling of Rothenburg’s historical and cultural sites, our journey might have only focused on the town’s fairytale atmosphere. By acknowledging my particular interest in Jewish history, we were able to witness a whole other side of the town.

Our ability to understand how Jews flourished and perished in Rothenburg would not have been possible without the dedication of locals who are committed to retelling Rothenburg’s Jewish story. Gussmann, a Protestant theologian, studied Judaism at Hebrew University. He is determined to inform others about the Jewish roots of Christianity and to make a personal contribution to peaceful Jewish-Christian relations. For over a dozen years, Schmidt has worked with Gussmann, as well as others, to create a walking tour and website.

When asked why Schmidt feels so compelled to offer tours that highlight disturbing times in Rothenburg’s history, he stated, “I am motivated to give visitors information about Rothenburg’s Jewish history so that people will remember and think about Jewish life in a positive way, in contrast to what is happening all over the world today.”