Phyllis Chesler calls things as she sees them. She is the prototypical New Yorker, one who does not back away from letting you hear her opinion or the truth – or both when they coincide.

Chesler has been an indefatigable fighter all her life on behalf of human rights, a legendary advocate in the vanguard of the feminist movement that matured in the early 1960s. She is a psychotherapist, scholar, thinker and writer of some 14 books. These include the groundbreaking international bestseller, Women and Madness, and more than a decade ago, The New Anti-Semitism, a hard-hitting call to arms regarding the resurgent, social scourge. She is also the co-founder of the Association for Women in Psychology and the National Women’s Health Network.

READ: Celebrating women’s graduation as spiritual leaders

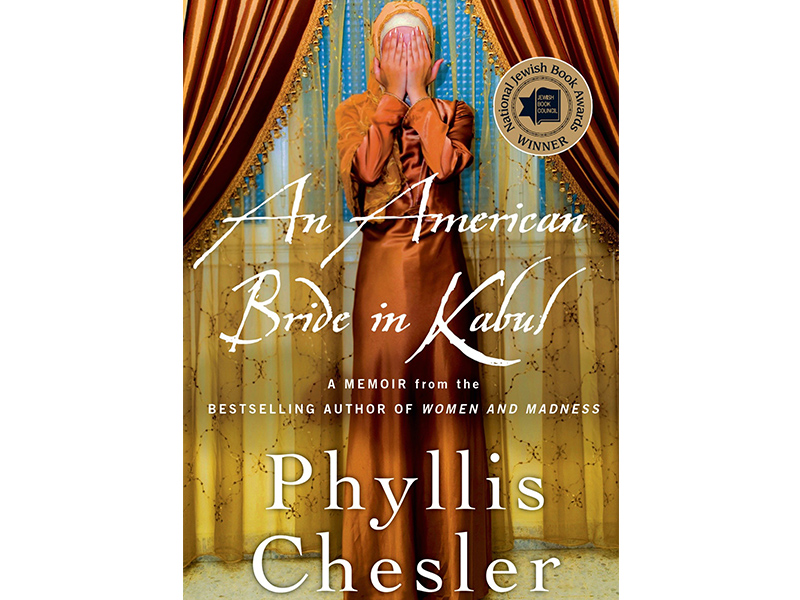

Chesler has never been known for pulling her punches and she pulls none in her latest book, An American Bride in Kabul: A Memoir.

An idealistic undergraduate student in New York in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Chesler falls in love with and eventually marries a suave, handsome, ostensibly wealthy, westernized young man from Afghanistan. Lured by a sense of romance, adventure and social purpose, she leaves her parents and the comfortable home in which she has been raised and moves with her new husband, Abdul-Kareem, to his native Afghanistan.

But the sense of adventure quickly collapses into a confined, suffocating existence as a kept foreign wife. The first hint of confounded dreams occurs as soon as she lands in Kabul when a government official confiscates her American passport. It is an ill omen of worse to come. She is not a citizen of Afghanistan, but in the eyes of the American diplomatic staff in Kabul, she is no longer an American. According to the customs and mores of Afghanistan, Chesler is property owned by her husband.

A “descent into Hell”

Still, the young bride develops a fondness for the natural splendour of the country and for some of her newly acquired family members who minister to her, especially during moments of high duress. Mostly, however, her time in Afghanistan as a foreign wife – indeed, a Jewish foreign wife – is a descent into hell.

Chesler describes her experiences in plentiful, pitiful detail. Her mother-in-law is an especially menacing presence in her life. “In the harem where I live, I am horrified by the way in which our slave-like servants are treated. The way my mother-in-law treats her female servants is criminal, tragic, barbaric, unbelievable – but apparently entirely normal in Kabul, both among the elite and among the peasantry.”

The social, cultural and spiritual misery of her life is matched by its physical misery, which reaches its dangerous nadir when she develops hepatitis. “I fear that I will die and be buried in a Muslim cemetery somewhere out in the countryside. I have just turned 21 and am seriously contemplating my death. Even this is not as frightening as Abdul-Kareem’s apparent indifference.”

Burqa “demoralizes both the wearer and all women who see her”

Chesler’s experiences in Afghanistan do not make up the entirety of the book. Rather, they provide the jumping off point for a wider reflection on the impact of those experiences on her life as a feminist, human rights advocate. She is unsparing in what she describes as the extremely cruel exclusion – the purdah – of women in Afghanistan and throughout the traditionalist Muslim world. Inevitably, she also shares her thoughts on the burqa. “The burqa is not religiously mandated. In the past, many Muslim countries either banned the burqa or allowed women and their families to choose how women would dress. From a human rights point of view, the burqa demoralizes both the wearer and all women who see her: hobbled, hidden, invisible, unable or forbidden to join the social conversation.”

This insightful account of her experiences and memories in Kabul, at times self-deprecating and humorous or biting and searing, also provides Chesler the opportunity to lift some heavy stones from her heart.

At her lowest physical and emotional point, seeking a way to spare herself further ill treatment, she writes: “This is difficult for me to write about. It is harder to admit that I was this foolish, this frightened, this alone, that I would actually jettison the religion of my ancestors for another religion about which I know absolutely nothing. But I did it. This is not something I ever tell anyone. Nevertheless I have never forgiven myself.”

At a later point in the memoir, Chesler summarizes: “This is an accounting of sorts. A young Jewish American woman once came to this wondrous Asiatic country (Afghanistan) and fled harem life. She finally uncovered the history of what happened to the Jews of Afghanistan and she has told their story in order to redeem her soul. A young Jewish American woman once loved a Muslim Afghan man, and although it could never work out, they continued talking to each other down through the decades of their lives.”

Subsequent sinister developments in the world, such as the rise of Al Qaeda, 9/11 and the shocking resurgence of anti-Semitism, become a backdrop for Chesler to apply some of the lessons of her Kabul life. She urges the West to face up to the challenge of arresting and turning back the march of radical, intolerant, xenophobic, violent Islamists.

READ: Author presents women-friendly versions of biblical stories

“I am shaken by the inability of many people to understand that evil and injustice truly exist and that one cannot win every single battle against them. I am even more shaken by the refusal of educated and progressive Americans to understand that the concept of a global caliphate is fuelling thousands of Islamist terrorists, all of whom have explosives and some of whom have nuclear weapons.

“We can and should rescue girls and women one by one and relocate them either within Afghanistan or externally; some groups are doing this. But we cannot rescue every woman in Afghanistan – or stem the tide of Islamist violence against civilians everywhere, not only in Afghanistan, without first defeating the Islamist ideologically, politically, economically and militarily.

“One cannot reason with evil. One must defeat it,” Chesler writes.

Her pointed words call to mind an occasion more than a decade ago when she told an assembly of journalists: “If we stand for peace and for justice, we may have to fight for it.”

Chesler received the National Jewish Book Award for An American Bride in Kabul: A Memoir. In light of the times in which we live, it is an instructive read.