Over the past 18 years, Brenley Shapiro has developed a successful career as a cognitive behavioural psychotherapist, sport psychologist and performance consultant. The founder of Heads Up High Performance, Shapiro works as the mental performance coach for the Ontario Hockey League’s (OHL) Peterborough Petes and has just been hired as a consultant by an NHL team.

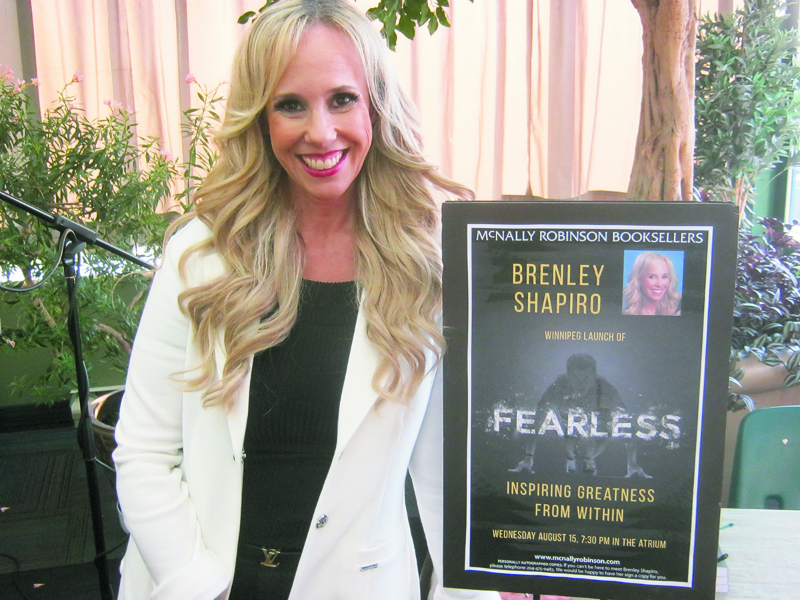

The CJN caught up with her at McNally Robinson Book Sellers in Winnipeg (her home town), where she was launching her first book, Fearless: Inspiring Greatness From Within.

What was your reason for writing this book?

The biggest stumbling block to success for athletes, as well as people in other walks of life, is fear – whether fear of failure, or not being good enough. Athletes worry about living up to expectations. What if they make mistakes? What does it mean if they are benched?

That fear – of failure, of not living up to expectations – and pushing through those fears in order to create a pathway toward success and be the best you can be – is the subject of Fearless.

In the book, I share my expertise gained through my work with athletes, with anyone else who may be being held back by fear. I have tried to present strategies that have proven successful in my work and that readers can use to help themselves, or their own children, in everyday life. I am confident that the techniques that I use to help athletes will build confidence, focus, motivation and ultimately teach others about building an overall mindset for success. My goal is to help people become the best they can be.

How important is talent in one’s success?

Talent is highly overrated. Talent accounts for only approximately 30 per cent of an athlete’s, or individual’s, long-term success. Success is largely built up on learning from your failures and persevering. The strategy I teach my athletes when faced with mistakes or failures is my three “F”s – find the problem, fix it and forget it. Basically, learning how to “fail forward” and learn and grow from it is how people get better.

What has been the response to the book so far?

The first run of 250 books sold out quickly and sales of the second run of 1,000 copies are brisk. It is gratifying to know that my book is having an impact. Helping people is what it is all about for me.

What was the challenge for you in writing your first book?

Writing the book was the easy part. The frustration was in the publishing and the design phase. I wasn’t sure that it would come out in time for my Toronto launch. I had trouble sleeping for weeks. I had to become fearless myself and take action. It was a liberating moment.

READ: TWO WINNIPEGGERS CELEBRATE THEIR 100TH BIRTHDAYS TOGETHER

Tell us how you became involved in sport psychology.

It was my own two sons’ experience in competitive sports that led to my involvement in sports. We were a hockey family and I saw a lot of crazy things going on at the rinks. People were yelling and screaming at the kids – even their own kids – and the referees. I saw fights breaking out between the parents. It was intense.

Sports is supposed to be fun, but what I saw was stressed out kids. The stress, the strain, the expectations these kids have from parents and coaches got me thinking about how I could help these children manage that stress. I used my expertise working with people’s thought patterns and behaviours, did more research and further training in the field of sport and performance psychology, and built a program to help athletes succeed.

I began doing workshops for athletes and got involved with a hockey school. I found that I was getting more and more calls from athletes. I loved it. I created my own company, Heads Up High Performance.

Over the years, I have developed a comprehensive program that combines theories of cognition and behaviours into mental skills training, along with scientific strategies using state-of-the-art technologies to strengthen neurocognitive processing.

Tell us about the Peterborough Petes.

For years, I have worked with teams and players from minor hockey, right through to the NHL, along with many players in the OHL. Half these 16-to-20-year-olds go on to play professionally. Many of the others aren’t sure what to do and where to go after hockey. It helps to have someone to talk to.

Last summer, I was invited to join the coaching staff. It has been a wonderful experience being part of the team. This is the first time that an OHL team has had a mental performance coach on staff. It is an indication of how professional sports is changing and recognizing the importance of sport psychology.

How are you received as a woman in the male-dominated world of hockey?

It has never been an issue. I call it out right away. When I first meet with the players, I joke that they are all wondering what position I played. I tell them that I have always had a love for the game of hockey and I do know a great deal about mindset and the mental side of the game and its impact on performance. When I help them see how much of a difference it makes in their game, I get their buy-in.

What was one of your biggest challenges as a sport and performance consultant?

That would be the call I got from a 45-year-old friend asking me to help him achieve his goal of running a 100-mile marathon. His longest distance previously was 60 miles and he had really struggled. He suffered from leg cramps, nausea and vomiting. The 100-mile run would take about 36 hours – without sleep. He knew that his ability to finish the race would be all mental.

In addition, I had just one month before the run to get him ready. I usually work with clients for at least three months before we begin to see results.

We developed a plan. I sent him to an athletic therapist to learn massage techniques. We developed a plan for managing nausea and injury. We came up with positive power statements for him to say out loud every day. I asked for a piece of the finish line to be cut off for him to hold as he was running for additional motivation.

He ran the race in 28 hours and finished in the 25th percentile of all runners who managed to finish the race.

This interview has been edited and condensed for style and clarity.