In a recent Globe and Mail feature, arts columnist Marsha Lederman presented a lengthy consideration of the German-born Vancouver photographer Fred Herzog, which included a detailed self-portrait, largely related to Lederman’s parents’ experience as Holocaust survivors and her own inheritance connected with that experience. Shortly after the piece appeared, Herzog was due to be considered for the prestigious ScotiaBank Photography Award (which he did not win).

As Lederman points out, Herzog’s career has undergone a steep rise in influence and success over the past decade, partly based on the increasing sense that his Kodachrome shots of Vancouver in the late 1950s and after are a basis for the important photographic tradition that has flourished in British Columbia.

The bulk of Herzog’s work remained little seen into the 21st century until a well-received show at Vancouver’s Presentation House Gallery in 2003 and a major retrospective at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2007 turned the tide. More recently, the National Gallery in Ottawa presented a smaller showing of his work.

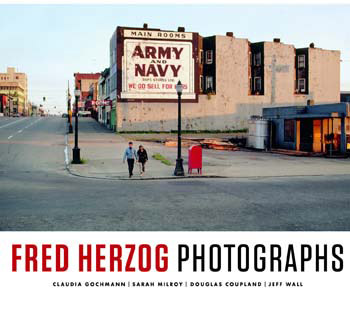

If you have not seen Herzog’s oeuvre in galleries, a lavish and lovely recent collection, Fred Herzog: Photographs (Douglas & McIntyre) is the latest among a series of book projects aimed at presenting Herzog’s photographic art to the average reader.

The occasion of Lederman’s interview with Herzog at his Vancouver home led to what could only be called an eruption – Herzog’s unsettling response to Lederman’s queries regarding a boyhood under the shadow of Nazism and war, his seemingly failed efforts to read carefully in Holocaust-related history, and, ultimately, Herzog’s apology for having stumbled into an area of consideration that he admitted he was ill-prepared to discuss with care or insight.

All of this, one might argue, provided a full-stop distraction from what is important about Herzog’s images, what has drawn galleries and collectors to them, and what it is that they contain that relates to Vancouver’s urban Jewish history. The latter issue, entirely uncommented upon, is enough to make a reader on Jewish Canadian daily life pick up Fred Herzog. But the pleasures associated with the book are many. The volume is outsized, allowing the publisher to present a substantial number of photographs from the 1950s and ’60s in the largest format available in print (if you are an art collector, Herzog’s Vancouver Equinox Gallery sells his images, printed in various sizes, from $1,800 and up).

Vancouver in the late 1950s and ’60s, especially the side of town that drew Herzog’s eye, is in many ways gone. The culture of colourful signs; the relative quietness of street traffic; the busy shopping culture on thoroughfares like Hastings and Main; the low-rise, small-scale business buildings of the east side of the old downtown have all largely been erased or gentrified following the city’s post-Expo 1986 successes.

Not every viewer of Herzog’s oeuvre will experience nostalgia at the sunset glow on Powell in “Crossing Powell,” or muse with interest over the dead emptiness at the corner of Main and Alexander, with its backdrop billboard painted on a red-brick apartment block, reading: “ARMY and NAVY Dept. Stores Ltd. WE DO SELL FOR LESS.” Army and Navy was the kingpin of east side Jewish businesses, run to lasting success by Samuel Cohen, who rose out of the pawn-shop culture of his compatriots and became a major landholder and retailer in the city – the Jewish counterpart to the anglo-elite Spencers and Woodwards, who sold many of the same things in buildings not so far from the big Army and Navy outlet on Cordova and Hastings.

The titles of Herzog’s photographs say nothing about the downtown’s specific ethnic history, and it may be that Herzog took no notice of it (though I doubt this). All you had to do was step into the smaller “Buy – Sell – Trade” outlets surrounding the Army and Navy to meet the middle-class, hardworking, often Polish- or Russian-born Jewish family man or woman, or son thereof, behind the till.

Although there is a fabulous array of subjects in Fred Herzog: Photographs – the front windows of Chinese cafés, the heartbreaking array of nighttime neon on Granville, the billboard culture of an earlier era, the disarray of pre-Granville Market False Creek (in one case on fire) – Herzog’s work is the best source if you want to see what the Jewish pawn and loan businesses of the postwar era looked like. There is little left of the Jewish downtown storefront culture of Canada’s western cities. Unless one has access to someone with the visual memory of a journalist and a penchant to tell stories about postwar street culture, this era is gone with the wind.

The introductory essays in Fred Herzog: Photographs make no mention of this aspect of the work they mean to present. They are by luminaries such as the novelist and pop culture pundit Douglas Coupland and the major Vancouver photographic artist Jeff Wall, among others. These writers have their eyes on other aspects of Herzog’s work. In his informative essay, Jeff Wall begins this way: “Until about 1970 there was something called old Vancouver, that city still characterized by the wooden houses in which most of its inhabitants dwelt… Vancouver in 1950, 1960 or 1970 had a real beauty.” That beauty, well captured in Herzog’s photographs, included the hardscrabble businesses of European-born Jews on the streets of the city’s east side.

Norman Ravvin writes of Jewish western Canadian life and history in his volume of essays Hidden Canada: An Intimate Travelogue. He is at work on a novel set partly on Vancouver’s once mean streets.