Had it not been for the adventurousness of Walter Neisser – a young German Jew and First World War veteran who set out to make his fortune in South America in the 1920s – his many descendants would likely not be here today.

Neisser (1897-1960) abandoned what seemed like a secure middle-class future in Upper Silesia in 1923 and travelled first to Argentina, then Chile, doing odd jobs, and finally settling in Peru. With few skills, but amazing drive and force of personality, Neisser created tremendous wealth and became a pillar of the Lima Jewish community and broader Peruvian society.

Those resources and influence not only meant a luxurious life for his immediate family, but also allowed him to bring some 50 relatives from Germany to Peru during the 1930s, sparing them from the Holocaust. That continued even after Peru officially shut its doors to Jewish refugees in 1938.

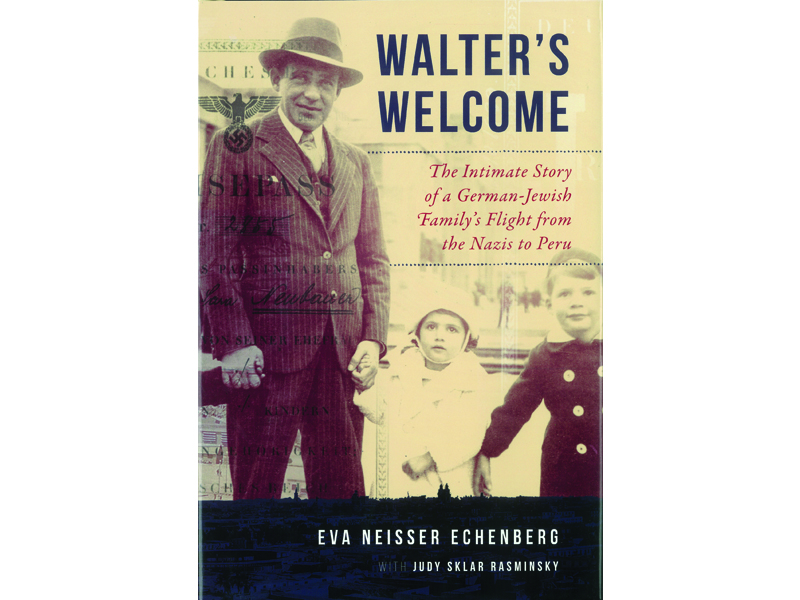

Thanks to her hard work recovering and translating more than 200 letters, his niece, Eva Neisser Echenberg of Montreal, has pieced together a portrait of this prescient patriarch in her new book, Walter’s Welcome: The Intimate Story of a German-Jewish Family’s Flight From the Nazis to Peru, which was co-written with Judy Sklar Rasminsky.

“Flight” might not be the right word, because as the correspondence illustrates, many of his family members were reluctant to leave Germany.

Walter Neisser’s younger brother Erich, Echenberg’s father, did go, along with three of his siblings. Neisser actually returned to Germany in 1935 and 1937, to persuade his relatives to get out. That he was responsible for so many people entering Peru is astonishing, given that only about 500 Jewish refugees from any country arrived there in the late ’30s.

READ: THE GREAT HUNT – THE SEARCH FOR THE HIDDEN JEWS OF LIBERATED EUROPE

These Jews were thoroughly German and could not foresee how far Hitler would go. In any case, Western nations were not generally willing to offer them asylum and it became increasingly difficult to get out of Germany, or even send mail abroad.

Understandably, they balked at leaving behind homes, businesses and social connections, to sail around the globe. Some were already in their senior years.

While most adjusted eventually, thanks to the fact that Neisser employed or supported many of them, they never fully integrated, Echenberg writes. Nor were the Peruvians welcoming, and citizenship was not extended to Jewish immigrants.

“Yes, this is a Holocaust story,” says Echenberg, “but it is also very much the story of the importance of family and a testament to the fact that one individual can make an enormous difference.”

She describes her uncle as “larger than life” and “the sun of our universe.”

Neisser and his wife, Erna, were the only ones who had Peruvian citizenship, spoke Spanish fluently and felt comfortable in the overwhelmingly Catholic society. The small Jewish community was also divided among its German, Sephardic and eastern European components.

Neisser was an importer and retailer of household appliances, founding an eponymous chain, but the real money came from gaining a monopoly on the country’s electricity.

Echenberg, who was born in Lima in 1942, is a retired Spanish teacher who, like most people of her generation, was educated in the United States and left Peru.

This book project was arduous: her German, the language mainly used in the letters kept by the family, was rusty, and some letters were in a dialect she barely knew. Moreover, the handwriting was often indecipherable.

Letters, of course, were the only means of intercontinental communication in those days. Neisser and his correspondents are generously descriptive and candid in their missives, lending an immediacy to their voices. They reveal both their everyday concerns and the toll of cataclysmic events shaping their lives – before, during and after the war.

They were trying to start fresh in a new, strange land, while at the same time desperately seeking news of those who they left behind. Those who did not flee write of their desperation in the postwar years – the desolation of being interned in concentration camps and the brutal poverty in Germany.

Between the letters, Echenberg offers context and personal reminiscences, with the result that Walter’s Welcome reads like an epistolary novel with a cast of characters, both noble and flawed. The inclusion of a family tree helps sort everyone out.

“Today, as millions of refugees flee their homelands in order to survive, previous refugee crises hold important lessons,” says Echenberg. “Canada and most other Western nations turned their backs on the Jews seeking asylum in the 1930s. Many perished, but some, like the members of my family, found a safe haven in countries they would have had difficulty locating on a map.”