The face of children’s literature in Israel is changing. To find out how, I spoke to three Israeli children’s authors to find out how today’s kids’ books are different from what they read growing up. Mirik Snir has published a hundred children’s books since 1982, Miri Leshem-Pelly, who published her first book in 1996, has become one of Israel’s foremost nature writers for children through her Professor Pitzponteva (Tiny Nature-Professor) series, and Yannets Levi is best known for his Uncle Leo’s Adventures series, first published in 2007.

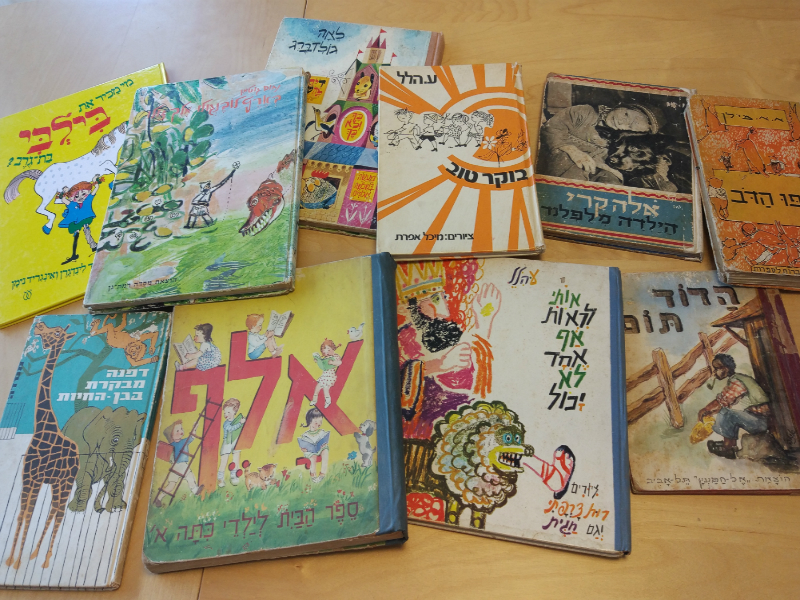

All three agree that children’s literature in Israel has always been very international. Growing up in the 1950s, Snir read books translated from Yiddish, including poems by Kadia Moldofsky, translations by Leah Goldberg, as well as new literature written by leading figures in the revival of the language like Avraham Shlonsky, Hayim Nachman Bialik, Nathan Alterman, along with Hebrew translations of foreign books, like one she remembers fondly which shared stories of children all over the world.

Still, a lack of specific children’s literature inspired Snir to use her background as a teacher and a mother of nine to create her own stories.

“I never planned to be a writer,” she says. She wrote what she saw was missing – high-interest easy books that helped kids teach themselves to read. “Books with a small amount of text are like a ladder,” she says. “First you read it to the children, then they ‘read’ it, looking at the pictures, then they start to look at the words, trying to figure out the secret of reading.”

When Leshem-Pelly was growing up in the 1970s, there was more choice, both local and international. “I was a very enthusiastic reader,” she says. “One book I really remember is Bilbi [Pippi Longstocking]. When I was five, I dressed up as Bilbi for Purim.”

Local favourites included Nachum Guttman, whose In the Land of Lobengulu King of Zulu was based partly on the author’s adventures in Africa.

Like Snir and Leshem-Pelly, Levi also loved reading. “Books have been part of my life ever since I can remember.” He, too, grew up on Leah Goldberg, but also international favourites like German writer Erich Kästner. “The world of books in Israel is very open to foreign literature,” he says. “We’re a society of immigrants. People came to Israel with all kinds of languages; they brought their favourite books, then had them translated here in Israel.”

For Levi, perhaps the biggest change in Israel today is the explosion of comic books, including many North American imports like Captain Underpants.

Even Leah Goldberg used to write comics… but it wasn’t as popular as it is today. Today, comics have become a very essential part of what kids are reading in Israel,” says Levi, who admits that he’s collaborating with an illustrator on a new comic book project.

“It’s a dream of mine – to create something for comics – but I also feel that local readers are very open to it now.”

READ: CHILDREN’S BOOK GETS ENDORSED BY ISRAELI PRESIDENT

There are also many more kids’ books today, Levi says, partly since publishing is less expensive and partly due to competition between Israel’s two bookstore chains. “This has made books very, very cheap and more available for most families.” Overall, he sees this as good news. “If you talk to publishers around the world, they’ll say the children’s department is the most active, and the most successful.”

Yet with publishers dreaming of replicating the success of series like Harry Potter, they may be less willing to take risks on original writing. Snir believes there may be too many foreign books in Israeli bookstores. “It’s easier for publishers to translate the ones that have already succeeded somewhere, and I think local literature is less well-developed because of that. They have to take a chance if they want to publish a new Israeli book, and they’re not doing it as much as they once were.”

Leshem-Pelly agrees. “It’s definitely making life even harder for authors in Israel. It’s a small market, and I’ve heard publishers say ‘only 30 per cent of our titles are going to be original.’” There also isn’t much government support for original Israeli children’s literature. But one positive effect of the influx of foreign books is that local production standards have gone up, with better-quality paper and illustrations.

“They need to compete,” she says.

Perhaps because the local market is flooded with imports, many Israeli writers and illustrators now set their sights abroad. Snir’s book When I First Held You, translated into English, was sent to thousands of families across North America by the PJ Library program. Her Hebrew books are also used frequently in schools abroad. Levi, too, has been translated into eight languages, with a ninth – Turkish – coming soon. Still, he sees the U.S. market as the toughest nut to crack. “They have the smallest percentage of translated books,” he says.

Leshem-Pelly has begun creating picture books in English specifically for the U.S. market, including Scribble and Author (2016, Kane Miller Books) and Penny and the Plain Piece of Paper (forthcoming 2020, Penguin/Philomel). Many others would love do the same. “Since I started publishing internationally, many authors now come to me asking for advice.”

Thanks to technology, Levi says, “it’s much easier to communicate with publishers and agents.” And though there may be cultural differences, Levi believes literature should overcome barriers. “Kids don’t choose where to be born; they don’t choose their identity, their nationality, their language. My books talk about things every kid loves, no matter where they’re from: finding treasure, flying with the clouds, reaching the land of chocolate, overcoming demons.”