Anthems are part and parcel of who we are as human beings. The more we change, the more the song remains the same. We sing different anthems at different times in our lives, at the moments when we change. And we love to return to the grounding of a good anthem.

I recall growing up singing O Canada at hockey games, not really thinking about the verse “in all thy sons command.” And so, with my own daughter and all women in mind, I was so excited when, in 2018, Canada’s Senate finally passed a bill making our anthem gender-neutral, replacing “in all thy sons command” with “in all of us command.”

The anthem still grounds us, but the times have certainly changed. Ensconced in the landscape of the Summer of Love in New York, the late Lubavitcher rebbe once remarked that the Jews must keep up with the times. Was he suggesting getting a subscription to the New York Times? No. Actually, he meant that to be a Jew is to be aware that time is on your side only if you keep up with the passage of time through the spiritual practice of study. Namely: “One should not only study the weekly portion every day, but live with it.”

For many wandering Jews in the 1960s, those words may have been enough to awaken a return to their zayde’s Yiddishkeit, or their grandparent’s Judaism, leading into the individual process of return known as baal teshuvah. But for many others, it would have rang hollow, insofar as religion was fast becoming a disenchanted realm. Was there an anthem that could be trusted to ring true any longer?

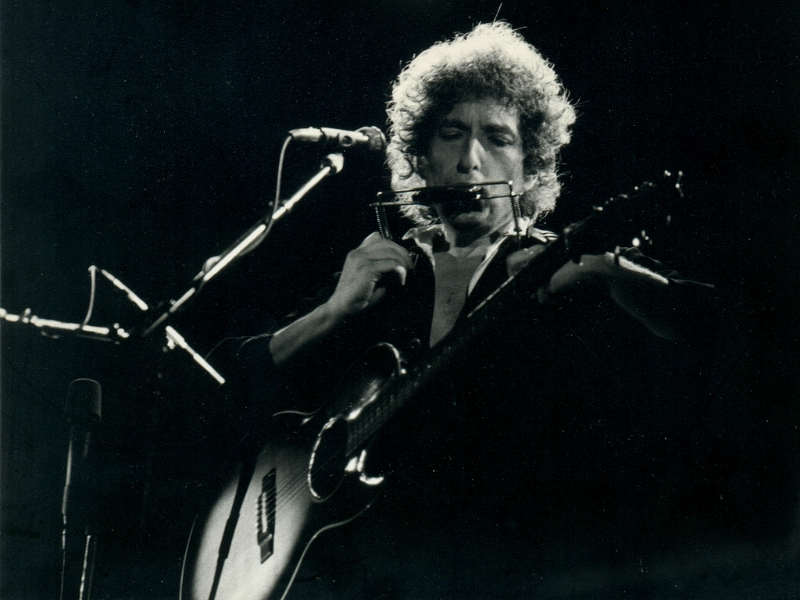

Amidst the deep suspicion of the ’60s, something did ring true to an entire generation of baby boomers, something that shifted their collective consciousness in 1963 and culminated with the Summer of Love a few years later. I would argue that the seeds of expanded consciousness that shaped that generation were planted the very moment when Bob Dylan channelled the modicum of a righteous thought without becoming trapped in delusional thinking to prophesize that which “whets its sardonic edge.” He sang a song that encapsulated – but also transcended – the protest of the folk scene like no other.

That song was “The Times They Are A-Changin’.”

It was quickly adopted as an anthem by causes far and wide, including the civil rights movement, as well as liberal and conservative political groups. Even rebellious youth heard it as a song about the generation gap. But as always, Dylan resisted reification of his lyrics. Rather, he continued pressing on for wider meanings, explaining in 1964 that his inspiration as an artist was to continually awaken his listeners from their spiritual slumbers. “It happened that maybe those were the only words I could find to separate aliveness from deadness,” he admitted.

Those timeless lyrics may have had nothing to do with the age of a given listener, but when Dylan performed “The Times They Are A-Changin’ ” after the assassination of JFK, it had already been superseded by the events of this tragic time, so his writing was, as Clinton Heylin wrote in Behind the Shades, a way of “consigning his art to the moment.” What we quickly discover is that the abiding truth of “The Times They Are a-Changin’ ” is that “temporariness is itself a permanent condition,” according to Christopher Ricks in Dylan’s Vision of Sin.

Dylan felt in his bones that this was a singular moment like no other, and encapsulated it brilliantly in the lyric that brings me to a comparison with the Hanukkah dreidel: “For the wheel’s still in spin/And there’s no tellin’ who that it’s namin’.”

What is it about this spinning top that captures our imagination, not only as children, but at all ages and stages of our lives?

To be able to see all of our life through the prism of the world unfolding before us takes remarkable depth of field. Many musicians, and most mystics, are such visionaries. Mystics like the Hasidic master, Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav (1772-1810), had such depth of field to envision the world as a rotating wheel. Rabbi Nachman could see in the spinning of the dreidel that the “wheel’s still in spin” because everything in life goes in cycles. Human becomes angel and angel becomes human; head becomes foot and foot becomes head – just as “For the loser now will be later to win … The slow one now/Will later be fast.”

Everything goes in cycles, revolving and alternating. All things interchange, one from another and one to another, elevating the low and lowering the high.

But here’s where Rabbi Nachman departs from Bob Dylan: even if temporariness is itself a permanent condition, still all things have one root. There are transcendental beings, there is the celestial world, whose essence is very tenuous, so angelic. And there is the world below, which is completely physical. All three come from different realms, but all have the same root. This vision, that the “wheel’s still in spin” because everything in life goes in cycles, is encapsulated in the very letters on the dreidel, which Rabbi Nachman corresponds to Hebrew words that represent the different realms:

• hay represents the Hebrew word hiyuli, which means primordial;

• nun relates to the word nivdal, which means transcendental (i.e., separate from the sensate world);

• gimmel corresponds to galgal, or the celestial (i.e., the angelic sphere, planetary constellations); and

• shin, which correlates to the word shafal, the physical realm.

The dreidel thus includes all of creation. It goes in cycles, alternating and revolving, one thing becoming another.

All of creation is like a rotating wheel, revolving and oscillating. The world is like a rotating wheel, spinning on target and out of control – like a dreidel, sometimes taking all the prizes and promotions, sometimes sitting with nothing. But no matter how much things interchange, they all revolve around the one root.

Dylan’s songbook, especially songs like “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” expresses the feeling that redemption is on its way. Rabbi Nachman could see that redemption is also an alternating cycle. Like in the Jerusalem Temple that is rededicated on Hanukkah, the highest are below and the lowest above. Redemption through rededication was for the sake of the Temple, the revolving wheel. For when the highest are below and the lowest above, it once again shows us that all things have one root.

That is the feeling that courses through us during the winter solstice, especially when we celebrate Hanukkah. This year, at a time when the light of redemption may require peering deeper into the darkness, let’s increase our dreidel-awareness. “As the present now/Will later be past/The order is rapidly fadin’/And the first one now will later be last/For the times they are a-changin’.”

Adapted from God Knows, Everything is Broken: The Great (Gnostic) Americana Songbook of Bob Dylan by Aubrey L. Glazer.