“I exist entirely because of silent film music,” says Alicia Svigals, a New York violinist. She’s not kidding, either.

The Yellow Ticket is a restored 1918 movie that Svigals was commissioned to write the score for. It’s a film that she connected with, despite the absence of spoken words, after taking on the challenge of musically mirroring the moods on screen.

But to Svigals, her work is intertwined with her grandmother meeting her grandfather when he was playing the piano at a movie theatre in New York. And it owes something to the fact that she answered a 1986 classified ad in the Village Voice, which was placed by a musician looking for others to play what had become an endangered form of Ashkenazic Jewish music.

After assembling the respondents, the man who placed the ad disappeared without a trace a month later. The rest of them named their group the Klezmatics, a play on the name of an over-the-top punk band, the Plasmatics.

Mercifully, no one needed to get that reference in order to be swept up in the band’s riotous klezmer sound.

READ: CANADIAN FILM EXPLORES THE ‘GOOD NAZI’

What defined the genre earlier in that century, a style centred on the clarinet, was actually an American approach. Eastern European klezmer music was considerably more string-based.

“There’s a reason why it was Fiddler on the Roof rather than ‘Clarinetist on the Roof,’” says Svigals, who was classically trained on the violin from age five.

“As a teenager, I got more into folk fiddling. I started studying neuroscience in college, then I dropped out and switched to ethnomusicology. Before long, I was a professional klezmer violinist. No one was more surprised than me that these geeky projects caught on.”

Svigals left the Klezmatics in 2001. Going solo carried her in different directions, including working on The Yellow Ticket. Svigals and Toronto-based pianist Marilyn Lerner will be playing along during screenings of the film in Brampton, Oakville, Ottawa and St. Catharines, Ont., in February. (She will also visit Kingston, Ont., to perform her solo show, Queen of Klezmer.)

The Yellow Ticket is the story of an adolescent in Warsaw named Lea, who sets out to study medicine in St. Petersburg. When she gets to Russia, she learns that she’ll only be allowed to work if it’s in a brothel, so she ends up working as a prostitute, while clandestinely studying to be a doctor on the side. The yellow ticket of the title refers to the low-status Jewish passport to this double life. (Prostitutes had to carry this ID card, as did Jews seeking to escape the Pale of Settlement). A twist in the tale has Lea’s medical professor finding out that she’s the illegitimate child that he left behind.

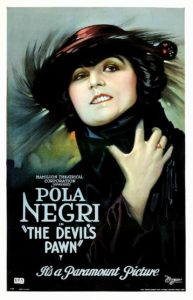

This is some wild stuff for a century-old movie, which also explains how the provocative concept of a “yellow ticket” inspired multiple scripts in that period. Svigals is accompanying the German one, originally called Der Gelbe Schein, also known as The Devil’s Pawn,which survived efforts to destroy all copies of it during the Second World War.

“It was a real revelation when I watched it for the first time,” she says. “A whole body of work, an entirely different art form, which I never really knew about. My job became to write music that would make the connection to the present. I want to make people feel like this could’ve been made yesterday.”

Svigals explains that the impression of silent movies as “people running around really fast” was just a technical glitch. Also, flicks like The Yellow Ticket came from an era when the projector itself was used like an instrument, increasing or decreasing the speed to sync it with live musicians.

Digital screenings mean having to stick to a more predictable pacing. But what plays out on screen is still evocative enough for Svigals to bring renewed energy to each show.

“The intertitles in The Yellow Ticket were sparse,” she explains of the wording designed to contextualize scenes. “Because they didn’t speak, all the acting was in their bodies and faces – some of it looks like dance, a choreography that’s quite beautiful. It’s not naturalistic: it falls somewhere between art and reality.”

A more visceral aspect of the film are the interior shots, through which Svigals feels she can practically smell the apartment of her great-grandmother, who emigrated to the U.S. from Odessa.

Meanwhile, exterior shots of Poland provide a unique glimpse of the neighbourhood that became the Warsaw Ghetto. It’s not like the people walking around in the shots were hired extras, either. They were ordinary Jews living ordinary lives.

“I was pulled down that rabbit hole from the first time I watched the movie,” says Svigals. “We put it on and it’s like old photos come to life: the furniture, the tchotchkes, the apartments. It’s just a very different form of time travel.”

The Yellow Ticket will be presented at the FirstOntario Performing Arts Centre in St. Catharines, Ont., Feb. 7; the Burlington, Ont., Performing Arts Centre, Feb. 8; Temple Israel in Ottawa, Feb. 10; and the Oakville, Ont., Centre for the Performing Arts, Feb. 16. Queen of Klezmer will be performed at the Isabel Bader Centre for Performing Arts in Kingston, Ont., Feb. 9.