A fine exhibit of visual art with Jewish and émigré roots has been drawing enthusiastic crowds to the Inigo Rooms, in London’s Somerset House since early July. Two years in the planning, Out of Chaos; Ben Uri: 100 Years in London, on until Dec. 13, has been dazzling visitors with its centenary celebration of works culled from the permanent collection of the Ben Uri Gallery and Museum.

A hundred years ago, the Jewish community in Whitechapel in London’s East End, founded an “art society,” featuring works by artists of Jewish descent. Eventually the Ben Uri – the art society that began as war raged in Europe and modernism was sweeping the art world –achieved accredited museum status.

Ben Uri is now home to a permanent collection of 1,300 works by 390 artists, ranging across 30 different mediums. Its reach is truly international. A wide variety of artworks greet visitors to Out of Chaos, from 21st-century works like the enchanting Morning Crescent by Frank Auerbach, to mid-20th-century pieces by Marc Chagall and Chaim Soutine, and finally, to very contemporary conceptual pieces.

As co-curator Rachel Dickson explains, the 1915 gallery was “named after Bezalel Ben Uri, the first artist mentioned in the Bible, who decorated the Ark of the Covenant in the Temple in Jerusalem. [The name] also relates to Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, founded in Jerusalem in 1906.” Ben Uri remains the oldest Jewish cultural organization in the United Kingdom.

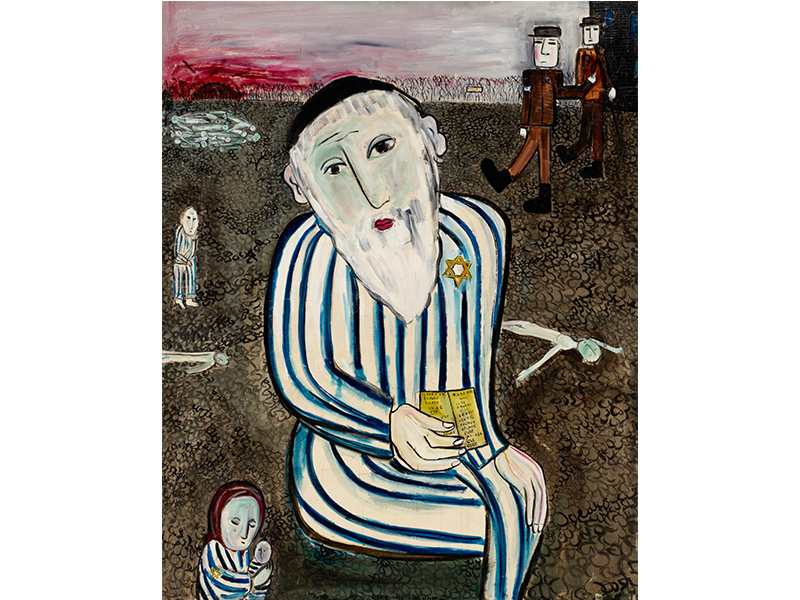

The themes of “identity and migration” anchor the centenary show, a refocusing, as it were, of Ben Uri’s roots that reflects London’s evolving multicultural realities. The celebration comes at a crucial time. Ben Uri’s temporary home in St. John’s Wood means that the public cannot view most of its vast collection, which has grown over the years to encompass migrant experiences both in and beyond Britain.

Ben Uri now describes itself as a “Museum of Art, Identity and Migration,” a “very recent change,” Dickson says, that came about “following an audit of the collection, when we realized about two-thirds of the works in the collection are by émigrés of some sort or other, born in one country, deceased or practising in another.”

Choosing from the museum’s vast collection was a daunting task. “The masterpieces of course selected themselves,” Dickson says, “but lesser works were much trickier.” Masterworks in the show include La Soubrette (1933) by Soutine. Writing in the Financial Times, critic Jackie Wullschlager called the Soutine “the best in the U.K.,… a violently tactile representation of a weary, wary maid in white apron.”

READ: Mural portrays 185 smiling seniors on one campus

Another stunning, rare piece is Chagall’s Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio (1945), a work dating from Chagall’s years as a war exile in New York.

Alongside famous names like these are also lesser-known artists, including a substantial representation of works by women. A portrait of two West Indian Waitresses, taking their break in a Lyons Corner House, was painted by Eva Frankfurther, whose family escaped Germany for Britain in 1939. Her work shows empathy for faces that were changing London in the 1950s – the same friends she made while working nights at a Lyons Corner House in Piccadilly and painting during the day.

It’s hard not to have favourites in a show of this depth, and the exhibit’s extensive website (www.benuri100.org) encourages viewers to comment on individual works of art, share their stories both on the site and on social media, and rate the pictures on a scale of one to five stars.

Many people love the painting chosen for the cover of the exhibit’s companion catalogue (by Rachel Dickson and Sarah MacDougall). This striking anti-war painting in the modern style, Merry-Go-Round (1916) by artist Mark Gertler, drew praise from such luminaries as writer D.H. Lawrence. Others did not understand its meaning, and there were no buyers for what has become such a “powerful image” in Dickson’s words.

Gertler, although frequently lauded by his peers, was unrewarded with success in his lifetime. In 1939, the Londoner of Jewish-Austrian heritage succumbed to despair. His unsold Merry-Go-Round – its vivid oranges and blues, its pleasure-seekers’ smiles forever frozen in terror – found a home at Ben Uri, before being sold to the Tate in 1984, when “Ben Uri was in difficult financial circumstances, ” says Dickson.

Ironically, it is now Ben Uri that needs to find a new home. Chair David Glasser says a successful search for a large space in central London will complete the evolution of the Ben Uri and create an accessible museum focusing on themes of identity and migration, underpinned by the Ben Uri’s own history and collection. (Certainly the timing seems right.) A bid has been made for 30,000 square feet in Piccadilly, just down the road from the Royal Academy. What’s needed now are philanthropists and visionaries to share and fund the Ben Uri’s vision.