The good news is that, after being granted an 11th-hour reprieve from the auction block, Marc Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel is back on display at the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) in Ottawa. The bad news is that on March 18, it will be returned to storage, where it had been languishing since 2012, save for a few months of schlepping to Hong Kong and Manhattan, as part of the NGC’s efforts to interest foreign buyers. When the National Gallery’s intention was discovered, there was such a public backlash that the NGC was forced to back down.

La Tour Eiffel is one of the 20th century’s most intellectually profound paintings. That no one at the NGC knows this might charitably be ascribed to its stunningly luminous beauty and disarming simplicity. The images it depicts could be out of a children’s book, so how could such cartoon-like figures be expressing ideas of immense depth?

Chagall’s body of work is all about the human mind as liberation, of spirit transcending body. A picture of a beggar floating above the shtetl Vitebsk (Over Vitebsk, 1914), a Jew standing on a rooftop playing a violin (Death, 1908) or a head separated from a body (To Russia, Donkeys and Others, 1911), convey the message that these Jews may have been poverty stricken, oppressed, living in dirt, without legal rights and never knowing when the next pogrom would start – but because they used their imaginations and their minds, they rose above and freed themselves, at least in spirit, from their downtrodden physical circumstances. La Tour Eiffel, however, states that civilization is an enslaving force. It is a painting about the human mind, not as a liberator, but as an oppressor.

What first strikes the viewer is the immense beauty of the natural, primordial world, with dense foliage, red flowers, a mauve sky and glorious, yellow sun illuminating the Eiffel Tower from inside an orange circle, itself enveloped in a red outer ring. Two people are emerging from the foliage, as though they are part of nature.

Chagall, depicting himself as a rooster, serenades his wife, Bella (“without (whose) inspiration I wouldn’t do any painting or engraving,” he said). Curvaceous, her womb elongated with fertility, she reclines on a couch that is itself part of nature. This is an earthly paradise where people can enjoy sex, while fulfilling the primary purpose of all non-human life – to, in the words of Genesis 1:28, be fruitful and multiply.

It is a scene of unadulterated happiness. And there can be no doubt that Chagall and his wife were very happy in Paris in 1929, when La Tour Eiffel was produced. Who wouldn’t be after living under tsarist oppression, through the privations of the First World War and the brutality of the Russian Civil War that followed the October 1917 seizure of power by the Bolsheviks? In a 1927 interview with L’Art vivant, Chagall called Paris a living school.

But all is not well in this picture.

For starters, the top of the tower is in the sky and outside the canvas. This is a reference to the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11:4) – “And they said: ‘Let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its head in the sky and we will make ourselves a name.’ ” The Tower of Babel is the ultimate symbol of hollow human self-aggrandizement, what happens when human knowledge is misused. And the figure flying too close to the sun is not the angel who appears in many Chagalls, but Icarus.

(While he was working on La Tour Eiffel, Chagall was immersed in the Old Testament, which he had agreed to illustrate for the venerable Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard. Unable to read Hebrew, he pored over a new Yiddish translation by Yehoash, which, according to The Jewish Encyclopedia, may be the greatest Yiddish translation ever made. He was so inspired that he visited Palestine and returned in 1931, when he painted landscapes of Jerusalem and interiors of Safed synagogues.)

Chagall goes even further, to make a most profound statement. Look closely at Bella Chagall’s face and you’ll see a woman who is not happy (this is really clear when one sees the actual painting, but not so visible from a reproduction).

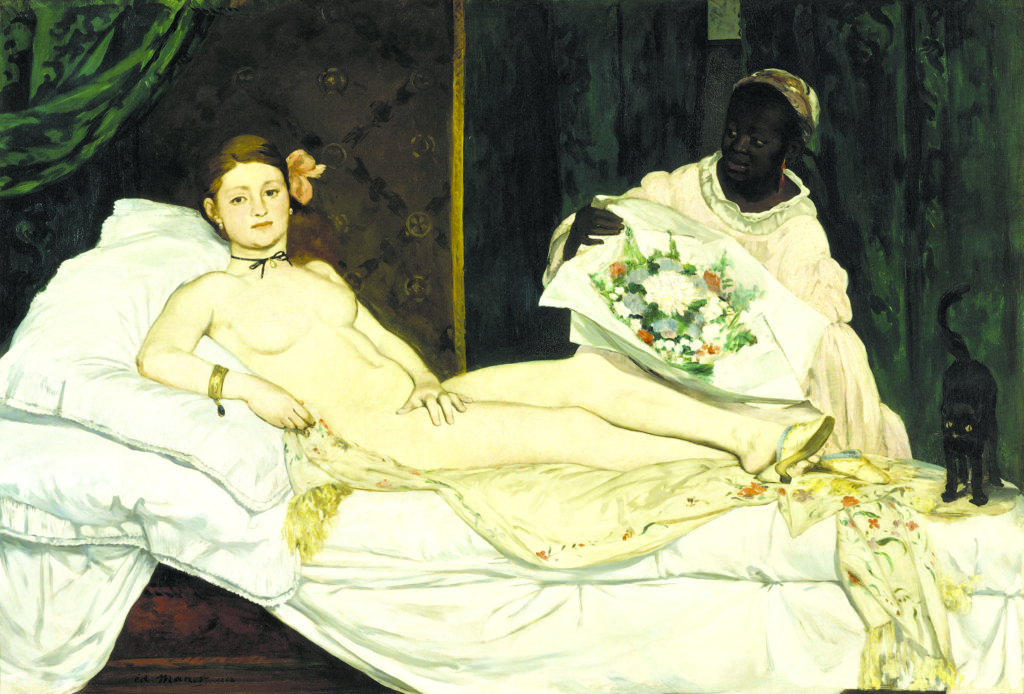

Her expression indicates that she is terrified by something she has just realized: she has just figured out that civilization, represented by the Eiffel Tower, has arrived and this means the exploitation, and even enslavement, of the weak by the powerful. As a woman, she is the most vulnerable. It is absolutely certain that this is what Chagall intends from the fact that she is reclining on a sofa, her head to the left of the canvas, leaning on her right elbow, with her hand covering her pubic area. Here, Chagall is citing French painting’s third most iconic image, Edouard Manet’s 1863 Olympia. When the Renaissance rediscovered the art of Greece and Rome, there began a long history of nude women sleeping or reclining with their heads mostly on the left side of the canvas. They started out as mythical figures, such as those painted by Cranach the Elder and Giorgone, became a high bred real woman with Titian’s Venus d’Urbino and were also painted by Francisco Goya and Diego Velazquez. In 1814, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painted La grande odalisque. Odalisks (“odal” is Turkish for “room”) were Ottoman virgin slaves who were at the bottom of the hierarchy in the sultan’s harem. Ingres’ odalisque is the sultan’s sex slave. Half her face is in shadow, but the half we see expresses unhappiness at being a captive.

READ: PROCESS OF PROPOSED CHAGALL SALE SHROUDED IN SECRECY

In Olympia, Victorine Meurent, Manet’s favourite model after his sister-in-law, the painter Berthe Morissot, is posing as a fille de chambre in a high-class brothel whose employees would go by pseudonyms. She is a contemporary odalisque. Based on the details of the two paintings, it is absolutely certain that Bella Chagall is Olympia. Each has a black cat. Olympia is wearing a black choker, while Bella has something decorative around her neck (that, like the choker, could quickly be turned into an instrument of control). Each painting features a bouquet of flowers. Olympia, like Ingres’ odalisque, holds a fan of feathers in her right hand. Chagall is making the statement that once the human mind figures out how to grow grain and domesticate animals, the subjugation of masses of humans to produce a surplus for the benefit of the few and the exploitation of women for sex is not far behind.

Olympia is pushed forward on the canvas – the painting has four distinct planes – as if displayed in a store window or on a stage. Her body is real, not idealized. She looks us in the eyes, her face full of sadness from the humiliation of her commercial exploitation, but nonetheless, she shows inner strength and dignity. Bella Chagall has just realized that by moving from a state close to nature to a civilized one, most of humanity will become conscripted into the service of the powerful few. The procreation she enjoys will be turned into sex that rich men can pay for. Meanwhile, Chagall, the blissfully unaware rooster, still hoping to get lucky, continues to fiddle with a foolish grin.

© SOCAN et ADAGP 2019, Chagall ® )

The Eiffel Tower, built for the centenary of the French Revolution as a shout out to French progress and modernity, became a flashpoint in the culture war that raged for the soul of France during the 19th century, pitting monarchists, clergy and other reactionaries against republicans, anarchists and other modernists. At a time when anything one did not like was blamed by both the left and the right on the newly emancipated Jews, Eiffel was called Jewish because “only a Jew could have submitted such a project” (though in reality, no Jewish skeletons hid in Eiffel’s closet). The Eiffel Tower was actually called “Babel! This monument to the Jew’s inexorable internationalism,” by those who wanted Paris to remain a fossilized city of beautiful old stone.

In the Torah, Babel describes the walled city states that emerged in the Fertile Crescent in southern Mesopotamia in the third millennium BCE. These were the first civilizations. They could not have come into existence without the cultivation of grain. Indeed, archeologists and anthropologists have recently proven that by the fifth millennium BCE, there were hundreds of small villages in this area cultivating grain as their main source of food. From this, they deduce that independent farmers and pastoralists resisted civilization for two millennia, primarily because it brought subjugation and control by the powerful. These cities were walled as much to keep their populations in, as to keep invaders out.

To the Torah, inequality among Jews is anathema. When the Jews conquered Canaan, each person was given an equal plot of land and no one ruled, only God. Concentration of power was prevented by the Jubilee, when, after 50 years, all land went back to the original family that owned it. Personally acquainted with oppression and possessed of a sixth sense that great artists sometimes have, Chagall was able to grasp 90 years ago what archeologists, anthropologists and evolutionary biologists are only now figuring out. He managed to compact the fundamental point of human history into a 100 x 81.8 cm space.

This makes La Tour Eiffel one of the most intellectually profound paintings of the 20th century. That its message is delivered subtly, organically percolating to the surface through layers of colour, makes it one of the greatest, the opinion of its current owner notwithstanding.