In the early 20th century, the Jewish community in Montreal created its own religious, cultural and intellectual space, including synagogues, schools, a Jewish public library, and a Yiddish language daily, the Keneder Adler. Behind these institutions was a group of remarkable men, both Orthodox and secular, who collectively built a Jewish community of considerable cultural creativity.

One of the most interesting of these men, though hardly the most famous, was Rabbi Chaim Kruger (1875-1934). Kruger, who came to Montreal in 1907, was a shoichet, one of a group of men who insured that Montreal Jews were daily supplied with reliably kosher meat. However this “day job” hardly defined him. Many of his colleagues from the slaughterhouse affiliated with specific congregations as rabbis or cantors, and Rabbi Kruger did serve as a cantor. This also did not define him.

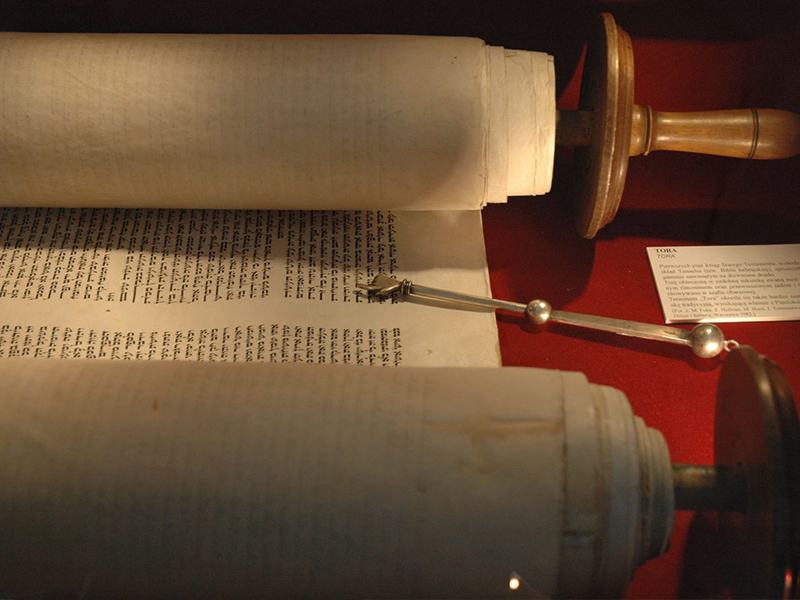

Beside these pursuits, Rabbi Kruger was a Talmud teacher (rosh yeshiva) in the Yeshiva of Montreal (known also as the Hebrew Academy), which was one of the first attempts outside New York City to transplant advanced talmudic learning to North America. The Montreal yeshiva, which did not survive the economic crisis of the 1930s, and of which we know precious little, was affiliated with the United Talmud Torahs and located at 412 Avenue Henri Julien.

However by no means did the slaughterhouse, synagogue, or yeshiva exhaust Rabbi Kruger’s energies. He was also a mainstay on the staff of the Keneder Adler for decades, and he did many things for that newspaper. It was he who regularly translated world news into Yiddish for the newspaper’s front page. He also created a number of features, wrote a regular column entitled “A Mirror of Life” – A shpigel fun lebn, and even tried his hand at a serialized novel.

Beyond these pursuits, he was a serious scholar of Jewish history and especially of medieval Jewish philosophy. Rabbi Kruger shared his love of such subjects as the Kabbalists of Safed, Philo Judaeus, Judah Halevi, Saadia Gaon and Maimonides with the readers of the Keneder Adler every Friday through much of the 1920s and the early 1930s. His columns on Maimonides were collected into a book Der Rambam, zayn leben un shafn (1933), which came out only shortly before he died at the very beginning of 1934.

Kruger’s book on Maimonides was taken seriously as scholarship, to the extent that it was reviewed in the Jewish Quarterly Review, one of the relatively few works in Yiddish to merit notice in the then journal of record of Jewish studies in North America. The book tells us a number of interesting things about Rabbi Kruger. The first is that he had mastered the technicalities of medieval Jewish philosophical concepts. He even attempted to explain these concepts in his newspaper columns, even though his explanations likely went way over the head of the average Adler reader.

The second is that Rabbi Kruger’s attempt to understand Maimonides’ philosophy impelled him to evaluate it in light of modern philosophy. Readers of his columns would have seen him compare and evaluate Maimonides with writings of modern philosophers such as Kant (Rabbi Kruger, like his contemporaries Hermann Cohen and Rabbi Joseph Baer Soloveitchik, found much harmony between the thought of Maimonides and Kant) and Nietzsche.

Whenever I think about Rabbi Kruger, I marvel at one thing in particular that marks an essential difference between his time and ours. In the early 20th century, the scholarly study of Judaism and Jewish history was normally pursued outside the university, in Jewish institutions of various sorts. While in Montreal in Rabbi Kruger’s time it was possible to study biblical Hebrew and Semitics at McGill University, there were then severe limitations to McGill’s receptivity to the academic pursuit of Jewish studies.

In our time, Rabbi Kruger might well have become a university professor of Judaic studies, but not then. Constrained by the realities of his day, he slaughtered animals for a living, pursued his love of Torah in the Montreal yeshiva, and his love of Jewish studies in the columns of the Keneder Adler.

Ira Robinson is a professor of religion and chair and director of the Concordia

Institute for Canadian Jewish Studies.