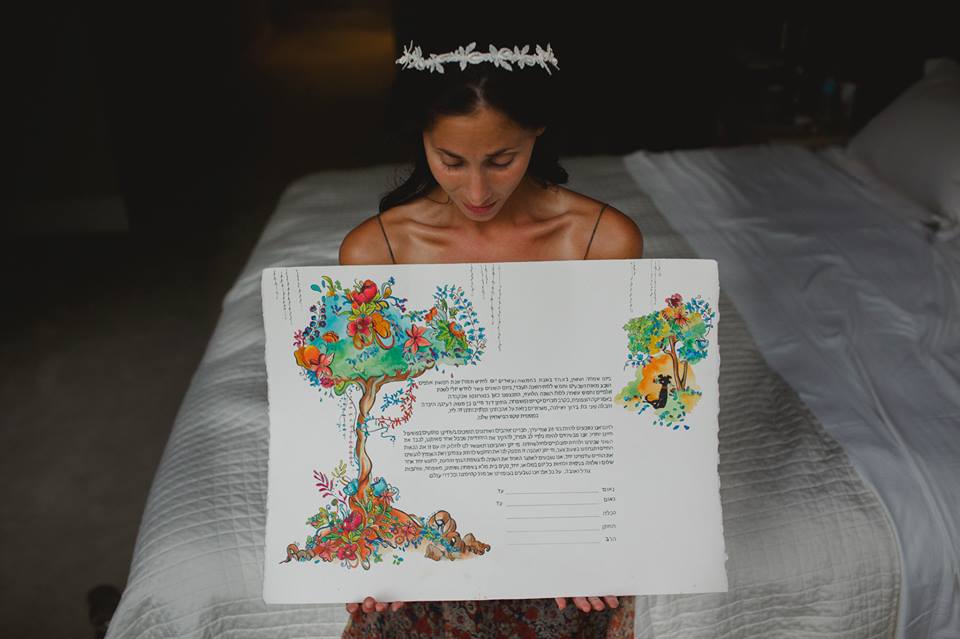

It’s not too often that you find a legal document that can also be a stunning work of art illustrating love and commitment. The ketubah, the Jewish marriage contract, has for thousands of years detailed a husband’s obligations to his wife during marriage and his responsibilities in the case of divorce. Beyond that, the ketubah has become a prized piece of Judaica which artists have elevated to become a document of devotion.

If it’s time to choose the design for your own ketubah, mazel tov on your engagement! (You may also want to check out my earlier articles about chupahs.) To see the very best ketubot, you could travel through dozens of homes and art galleries. But you’re probably too busy for that. You can see what the world has to offer with a click of a mouse. And even if you’re NOT getting married, you still can enjoy a tour of one of Judaism’s most interesting and beautiful documents.

As Ohr Somayach points out, “this contract is ordained by Mishnaic law (circa 170 CE) and according to some authorities, dates back to Biblical times. The ketubah, written in Aramaic, details the husband’s obligations to his wife: food, clothing, dwelling and pleasure. It also creates a lien on all his property to pay her a sum of money and support (200 zuz and 200 silver pieces) should he divorce her, or predecease her.

Most ketubot in recent centuries have conformed to a standardized text but as Eliezer Segal writes, some ancient ketubot addressed the termination of the marriage at the initiative of the husband and even the wife. Here’s an excerpt from the oldest existing ketubah, dating from the 5th century B.C.E. originating on the island of Elephantine in the Nile. “If at some time Ananiah should stand up before the assembly and declare: ‘I reject my wife Jehoshama. She shall not be my wife!’ then he is obligated to pay divorce money … And if Jehoshama should reject her husband Ananiah and declare before him ‘I reject you and will not be your wife!’ then she shall be obliged to pay the ‘divorce money.’”

For more on the history of the ketubah, visit the entry at The Jewish Encyclopedia.

Although the ketubah is essentially a legal text, the adornment of this document is a cherished tradition. As Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library eloquently puts it: “These decorations transform the ketubah from a dry legal document into a work of art, and a window into the world and culture of the Jewish communities that produced them.”

In addition to the ketubah that might be hanging on your wall, there is also the tractate of the Talmud, titled Ketubot. As noted by the scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz in his Introduction to Ketubot, it deals with “issues of marriage relationships between husband and wife – marital relations, mutual responsibilities, and financial agreements” and much more.

Trying to learn Talmud in isolation is a major challenge, even for veteran students. If you don’t have access to local study groups, you can take advantage of online audio classes such as those offered in depth by Rabbi Aryeh Lebowitz of Yeshiva University and highlights by Conservative Rabbi David Greenstein. You can follow along with the original Aramaic and Hebrew text along with an English translation at Sefaria.org.

After spending months learning Ketubot, Rabbi Jay Kelman points out that the Talmud has much to teach us about the relationship between wives and husbands, “the ketubah is the bond that marks the love of man and woman, and that of G-d towards the Jewish people.”

Ilana Kurshan has gone a different route, one which might have caused the rabbis of yore to do a double take. Upon completion of a page of the (often arcane) arguments and parables found on a page of a Talmud, Kurshan has summarized them in a limerick! Here are some of her musings on Ketubot:

| (17a)

How to dance before a bride Who is lovely, but on the inside? Hillel says: “Say she’s pretty” Says Shammai: “A pity To lie.” “But you must!” Hillel chides.

|

(52b)

A father should dress his girl well So a suitor will think she looks swell He will glance at her rump And then up he will jump: “I must marry her! Please, will you sell?”

|

| (41b)

Do not keep a dog in your house (It could bite off the head of your spouse) Or a rickety ladder (It might slip and shatter And injure much more than a mouse.)

|

(43b)

If a woman’s had husbands die twice We suspect her of some sort of vice For if both husbands die We can’t help asking why (Is it poison she puts in their rice?)

|

Next time, a look at the text of the ketubah and whether you really have to live up to its ancient legalese.