To the thousands of young people he spoke to over the last two decades, Bill Glied had a simple response to something as monstrous as the Holocaust: Every day, kiss your mother or father – or the ground you walk on because you don’t know how lucky you are to live in Canada. And with one good deed a day, whether it’s holding a door open or helping someone across the street, you can make the world a better place.

“He would say that if he touched one person out of every class he spoke to, he had an impact,” reflected Glied’s daughter, Michelle Glied-Goldstein.

As a Holocaust survivor, Glied had every reason to be mad at the world. If he was, you wouldn’t know it, and if he was taking it easy later in life, you wouldn’t know that, either. “Most people are winding down” in their senior years, observed another of Glied’s three daughters, Sherry. “He had a rocket on him.”

A fixture on Canada’s Holocaust education scene, Glied was a popular and tireless speaker at schools, conferences, churches and synagogues across the country, and was a regular on the annual March of the Living, accompanying students to the sites of former Nazi death camps in Poland.

Asked once to explain why he participated in the March, he reasoned that he did not want the Holocaust “to disappear into history like the Armenian genocide.” But the larger motive was to help young people understand their weighty responsibility “to make sure that what happened should never happen again.”

Glied has his own take on the dangers of ignoring history. “I keep on saying that [young people] must listen to the history that was passed, because if they don’t remember the history, the history is going to come back to them,” he said less than a year ago before addressing a synagogue in Saskatoon.

Despite his best efforts, it seemed as though many were not listening, or hearing. “I’m studying history all the time, and what is happening now is so reminiscent of what was happening in Europe in the 1930s,” he warned.

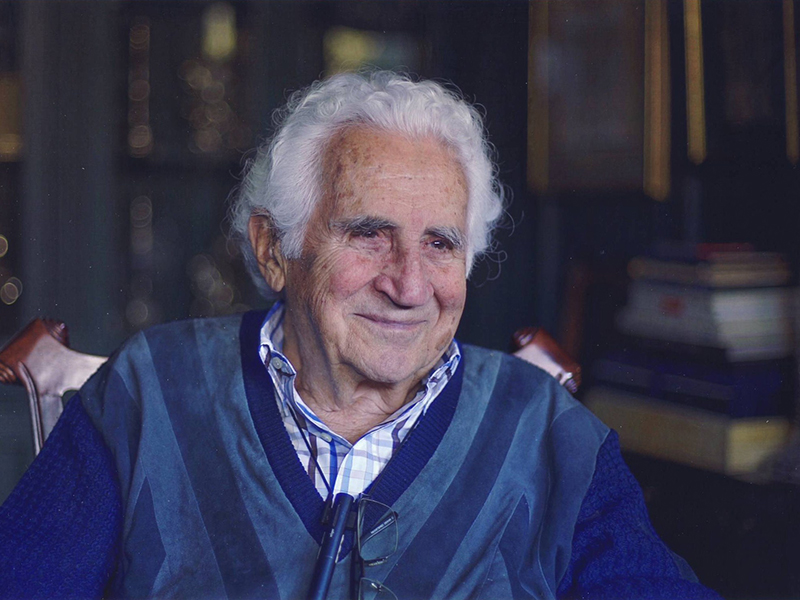

Glied died unexpectedly in Toronto on Feb. 17. He was 87.

He made headlines in 2016 when he flew to the German city of Detmold to testify in the prosecution of one of the last surviving guards at Auschwitz, Reinhold Hanning. Anyone expecting bitterness and blame was disappointed.

After describing how his mother and sister were shunted to their immediate deaths at Auschwitz and how he and his father became slave labourers, Glied said he had come simply to bear witness, “not because of hate,” noted the Globe and Mail’s obituary on him. “I came because, while I don’t hate, I cannot forget.”

Hanning was convicted as an accessory to 170,000 murders and sentenced to five years in prison. He died last May at age 95.

Glied decided to testify because he wanted to tell his story in Germany, on the record, in a German court, said Michelle. “With the conviction, it’s there forever.”

Thomas Walther, the retired judge turned prosecutor who represented co-plaintiffs in the case of Hanning and other former Nazi guards, flew from the German town of Lindenberg to pay a special shivah call on the Glied family in Toronto. Walther’s words to The CJN about his former “client” were especially poetic.

“He protected his soul for his future,” Walther wrote. “He protected the beauty of his soul for his fabulous family and his friends in the world. He never showed how arduous sometimes it was for his lovable personality.”

Through his testimony and memory, Glied preserved Auschwitz “for eternity. He showed my country that it is never too late for justice.”

A strapping six-footer with his trademark shock of white hair, Glied was recalled as soft-spoken and humble. “He was gentle and kind and the kids loved him,” recalled fellow Toronto survivor and educator Anita Ekstein, who travelled with Glied many times on the March. “They listened with rapt attention to his every word.”

He was born Vojislav Eliezer Glied in 1930 in the Serbian city of Subotica, a stone’s throw from the Hungarian border. The observant Jewish family owned a flour mill. When Germany invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941, Hungary annexed the city.

That meant anti-Jewish laws were now in effect. “People I considered my friend all of a sudden became enemies,” Glied recalled in a 2015 Globe and Mail profile. “People who were my parents’ friends and associates all of a sudden became strangers.”

But Jews in Hungary were spared deportation until spring, 1944. Glied was 13 when he, his parents and sister were driven from their home and loaded onto a cattle car. “It never occurred to me, or to them, what the end of that train ride would be,” he told Postmedia in 2016.

After a nightmarish two-day ride, the end was Auschwitz, where bewildered passengers encountered bedlam, blinding light, and SS men swinging clubs. Glied’s mother, Maria, and his eight-year-old sister, Aniko, were led to the gas chambers straightaway. Glied and his father, Alexander, were kept for slave labour.

After a few weeks at Birkenau, the pair was shipped to Dachau, then to one its subcamps, Kaufering III, where they toiled 12 hours a day to build a huge underground airplane factory. The father shared his meagre rations with his son, something Glied always mentioned in his talks.

As the war drew to a close, both contracted typhoid fever and his father died eight days before U.S. troops liberated the camp in April 1945. Glied was his family’s sole survivor.

Glied came to Canada in 1947 and was soon sent to a sanatorium outside Hamilton after a doctor suspected he had tuberculosis. There for 18 months, he perfected his English with non-stop reading, a habit he kept and which would lead to a polymath’s knowledge of history, politics, Judaism – even mathematics.

In the mid-1950s, he started a business, Cadillac Lumber, which would grow to great success. In 1959, he married Marika Nyiri, who had been hidden in Budapest’s Jewish ghetto during the war. He didn’t talk about his experiences, until he took his teenaged daughters to Dachau to see the mass grave where his father was buried.

Nate Leipciger, another educator and fellow Auschwitz survivor, recalled that he had Glied collaborated on the creation of the Sarah and Chaim Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre.

“He was knowledgeable and very bright and very sensitive as to what would be appropriate to show and what not,” Leipciger told The CJN.

Once, on a Shabbaton, “we stood together on the shores of Lake Simcoe, shivering and hugging each other as we remembered standing in the concentration camps, exchanging positions to shield for a few minutes the freezing wind that tore through our threadbare clothing.”

Leipciger said his sorrow on losing Glied is “great.”

Max Eisen, another local Holocaust speaker, said his old friend Glied was, “as we say in Hebrew, ‘stronger than a lion and swifter than an eagle.’ This is the memory I will hold onto.”

Glied’s daughters agree that their father maintained an unusually sunny, optimistic outlook. “He believed in people,” said Michelle. “He thought that at heart, everyone was good.” He expressed as much. “I feel that human beings are by nature good, that they’re not evil,” he said a few years ago. “If I didn’t believe that, there is not much sense in human existence.”

Few on the March of the Living will forget Glied’s speech in 2016 on the outskirts of Lublin, Poland. “Why are you a Jew?” he asked the assembled teenagers, standing before a mound of human ashes at Majdanek, the former Nazi death camp (the speech was read at his funeral).

“I’m a Jew,” he said, “because I believe that all human beings are created in the likeness of God and therefore all racism is foreign to me…because I have an obligation to help and be hospitable to strangers, to visit the sick…and most of all, to make peace between people.”

As Eisen put it, his greatest legacy was his family. He is survived by his wife, daughters Sherry, Tammy and Michelle, eight grandchildren, and a great-grandchild on the way.

On May 8, a major event in Toronto will mark the 30th anniversary of the March of the Living. Over 100 Holocaust survivors who have taken part since its inception will be honoured. According to the March’s national director, Eli Rubenstein, the only confirmed speaker to date was Bill Glied.