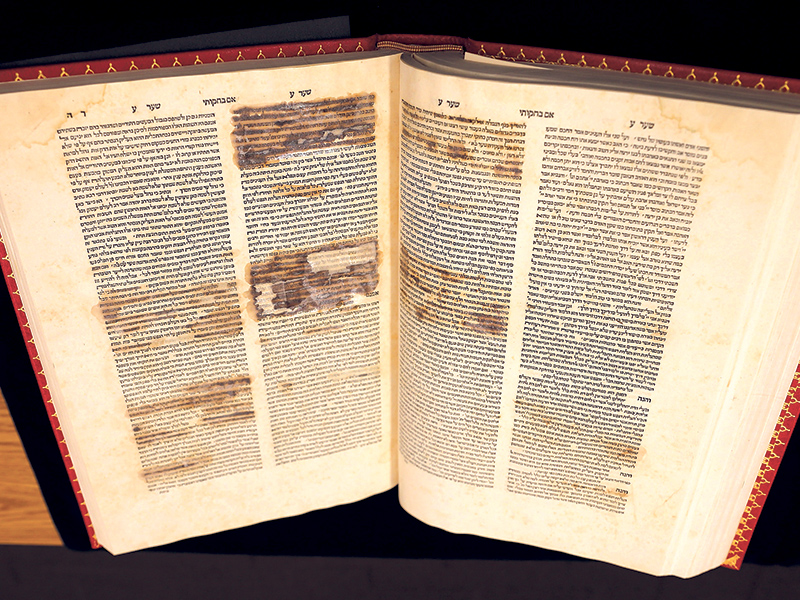

Almost 500 years ago, the Catholic Church censored this Jewish volume. Now, Canadian conservationists have restored it to its original glory.

There’s no time like the present, the adage goes, especially in this case. With all its technological advances and innovations, the present has opened a window on the past.

Over the summer, archivists and conservationists outside Ottawa used all the modern tools and methods at their disposal to reverse time and lift a censor’s final fingerprints off the page in the painstaking restoration of a rare 16th-century Jewish volume to its original glory, or at least, readability.

It took one year and some 200 hours of meticulous work, precision and patience to bring to light the words of Akedat Yitshak (The Binding of Isaac), a book from the famous Jacob M. Lowy Collection at Library and Archives Canada (LAC).

First published in Salonika in 1522, the edition before the LAC’s Preservation Centre in Gatineau, Que., was printed, according to some sources, in Venice, in 1546 or 1547. Authored by the prominent Spanish rabbi Isaac ben Moses Arama, who was expelled by the Inquisition and died in Naples in 1494, the book is a lengthy philosophical and allegorical commentary on the Pentateuch written in the form of 105 “portals,” or sermons.

It’s considered a classical work that unites philosophy and Jewish homiletics. “It is very sophisticated in its approach, drawing heavily on Aristotelian philosophy,” said Barry Walfish, the Judaica specialist at University of Toronto Libraries. “It is difficult and quite wordy, but it was a significant and influential work in its time.”

It was also considered dangerous. So much so, that it soon came under the scrutiny of the Catholic Church, which was on the lookout for anything it perceived as heretical or offensive. That included references to gentiles, or nochrim, and passages judged to be critical of the New Testament.

So eager to please were church censors that they signed the volumes they redacted. The edition of Akedat Yitshak before the LAC bears the signature of Domenico Irosolimitano, a notable and busy censor of Hebrew texts who died around 1620.

More notable is that Irosolimitano was a Jewish convert to Christianity named Samuel Vivas, who had been a Jerusalem-based rabbi to boot.

Walfish stressed that it’s important to distinguish between censorship and expurgation.

“Censorship involves not allowing a text to be published at all, or having parts of it removed before it is published so it never sees the light of day,” he told The CJN. “Expurgation involves erasing offensive material from an already published text. This is the phenomenon under discussion here.”

The practice was common in Italy from the mid-16th to the early-17th centuries. The censors were often converts from Judaism, so they knew what they were reading.

“Hundreds of books were expurgated, often very mechanically, erasing references that might be considered offensive to Christianity,” Walfish said. “Any mention of idol worship was removed, because Christian clerics believed Jews thought that Christianity was an idolatrous religion.”

In 1589, Walfish pointed out, the pope expanded the ban on the Talmud to other Jewish books. In a few years, an Index Expurgatorius, or list of books requiring expurgation, was established. It contained 420 titles.

While polemical passages against Christianity were common in some Hebrew texts of the day, “I’m not sure to what extent Arama engaged in polemical activity,” Walfish said. “I’m not aware of that being a major focus of his work.”

The censor certainly felt it was, and most pressing for conservers in Gatineau was to address the physical damage he had done to 38 “leaves,” or pages, of Akedat Yitshak.

Words, lines and whole paragraphs were blotted out using plenty of dark iron gall ink, which was concocted with iron salts and vegetable sources. Homemade and cheap, it was the standard writing and drawing ink in Europe for centuries. But because it contained iron, the ink oxidized and corroded over time, its pigments degrading the paper to a fragile, brittle state, and in some cases, even eating through the pages, causing holes. That’s what happened with Akedat Yitshak.

Restorers had to move fast to prevent further decay. But where and how to begin? Manise Marston, a book conservator at Library and Archives Canada assigned to the daunting task, chuckles at the question.

“Initially, there is a lot of testing involved,” searching for the presence of certain undesirable ions, she told The CJN. The censor’s ink was “very unstable” and had its desired effect. “It eventually degraded so much that the passages were completely gone. My job was to stabilize it.”

Turns out Marston bested Irosolimitano and his heavy pen.

Employing state-of-the-art techniques, she used a syringe to apply a gelatin-based adhesive to the text, followed by a gossamer-thin paper called Berlin Tissue that’s tricky to handle and took three or four days for Marston to make. In Europe over the past few years, it was discovered that the gelatin would stop the degradation process. “It’s a really big deal in conservation for us,” she said.

Ethanol was used to activate the gelatin. “You have to have just the right amount of ethanol or the adhesive will evaporate,” Marston explained. “You have to be very precise.” Too much or too little adhesive and the tissue won’t stick.

The ultra-thin Berlin Tissue stays on the paper permanently. A “suction plate” avoided any staining during application. “I got very good at it,” Marston said with a laugh, “but it took me 200 hours.”

An online LAC publication noted that as if those were not major challenges, Marston “also had to deal with the added level of complexity that a book, or bound item, presents… And each time she treated an area, she had to readjust the book using weights to support the text block in the right position while she adhered the tissue and applied additional weights until it dried. Each treatment took approximately five to seven minutes to apply on each side of the page.”

The results reveal the hitherto hidden Hebrew passages, but still framed in the tinge of the censor’s ink. Holes now occupy other passages where text once lay.

Marston encountered pieces of the book that were missing, “but there were also pieces that had broken away. It’s almost like a puzzle piece.” The fragments were reattached in their correct place. “It was very exciting, in a way, because we’re re-forming what was there.”

Leah Cohen, curator of the Jacob M. Lowy Collection, felt the same way. The restoration had “a kind of an archeological feel about it,” she told the CBC a few weeks ago.

Cohen told The CJN that the project has left her excited overall. But “I found it personally a little bit disturbing that some of the censors [of this and other volumes] were Jewish converts to Christianity. I found that upsetting.”

The censor of Akedat Yitshak, she pointed out, took particular umbrage at any reference to mashiach (the Messiah) or mention of nochhri – gentile.

The Lowy collection holds 30 to 40 books that were censored by the church in Italian city-states, Cohen said. But the iron gall ink used in those volumes is not as corrosive as the one used to censor Akedat Yitshak, “and so we will not be requesting the restoration of the other censored books.” Also, some books were only lightly censored. “The extent of the expurgation varies.”

In the coming months, restoration will be carried out on books that have “other issues.” Some typical problems are detached bindings, separated boards of the cover, torn spines, rotting leather or warped vellum binding that requires flattening.

READ: JEWISH GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF TORONTO SEEKS HOME FOR ITS BOOKS

It was in 1977 that Canadian industrialist Jacob M. Lowy, who died in 1990, donated his collection of rare Judaica and Hebraica to Library and Archives Canada. The 3,000 or so volumes and some 2,500 reference works include first and early editions of the Talmud, Hebrew, Latin and Italian volumes produced in the earliest stages of movable type, and more than 120 Bibles in various languages.

Cohen announced recently that she was leaving her position as curator of the Lowy collection after serving for six years. Taking over will be Michael Kent, a curator and ordained rabbi who will continue teaching at Torah High Ottawa.

The restored Akedat Yitshak, meantime, is not currently on public display. Scholars and others may examine it, by appointment only, at the Lowy Collection, 395 Wellington St. in Ottawa.