Stanley Hartt, businessman, well-connected lawyer and top-tier civil servant, died of cancer at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Hospital on Jan. 3. He was 80.

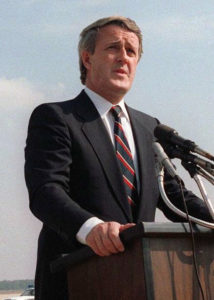

As deputy minister of finance (1985-88) and later chief of staff to former prime minister Brian Mulroney (1989-90), Hartt played a key role in a number of major government initiatives, from the much-maligned Goods and Services Tax (GST) and wrangles over the constitution, to free trade with the United States and the movement to free Nelson Mandela, Mulroney told The Canadian Press.

Hartt was among the “most outstanding public servants of our country,” Mulroney told iPolitics. “He combined both an extremely brilliant mind with a delightful sense of humour, together with a remarkable capacity to analyze complex issues and produce policy options.

“I will always remember Stanley as a warm and highly valued friend of some 50 years.”

Stanley Herbert Hartt was born in Montreal in 1937. He grew up in the heavily Jewish garment district that was made famous by Mordecai Richler, he recalled in a self-written obituary, which made up part of his autobiography.

READ: WHY JEWS WERE RED TORIES

His father, Maurice Hartt, was born in Tacu, Romania, “a tiny village so minuscule it does not appear even on detailed maps of the administrative division of Moldovia,” Hartt wrote.

The family migrated to Canada in 1907, when Maurice was 12, “amid dangerous anti-Semitic violence in the old country and a challenging Canadian immigration policy, particularly hostile to the influx of Romanian Jews.”

Stanley Hartt attended the Jewish Peoples School, which stressed Hebrew and Yiddish language skills, “with a definite Zionist bent. It was not intended to teach religious fundamentals like the nearby Talmud Torah School, but adhered to the curriculum of the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal, so that its graduates could go on to secular high schools.”

Meanwhile, his father, who had become a lawyer, found success in politics. Maurice Hartt was elected to Quebec’s national assembly as a Liberal in the riding of Saint-Louis in 1939 and re-elected in 1944.

He was then elected to the House of Commons in 1947, in the riding of Cartier. The seat had been declared vacant when Communist MP Fred Rose was convicted of spying for the Soviet Union. Hartt was re-elected in 1949, but died in office in 1950.

At McGill University, Stanley Hartt earned a master’s degree in economics and placed first in his class in law school, where he worked as a teaching assistant while studying. In 1965, he won the prize for highest standing in the bar exams and was asked to join Stikeman Elliott, the firm at which he had been articling.

As Hartt recalled in his own obituary, the firm’s founders, Heward Stikeman and Fraser Elliott, took him to lunch at the Windsor Club and informed him that he would be hired – not despite being Jewish, but because he was.

“Asked what that meant, the two founders revealed that many of their clients actually thought that Stikeman was a Jewish name (it was not – it was a venerable English family name) and there were a significant number of Jewish clients who were unaware that, until that time, Jewish lawyers were rare in establishment law firms in Canada,” Hartt recalled.

After his “old friend” and colleague from the firm, Brian Mulroney, became prime minister in 1984, Hartt was named deputy finance minister. One of his first tasks was dealing with Ottawa’s shuttering of two Alberta-based banks and overseeing stronger legislation governing financial institutions.

The unpopular GST was a tough sell, but Hartt believed it was the right thing to do.

In 1989, he became Mulroney’s chief of staff, “a role much less focused on policy and more on day-to-day management of the PMO.”

This included handling various crises, such as “a hijacked bus driven onto Parliament Hill with an armed man threatening the passengers directly in front of the Peace Tower; the discovery of cyanide injected into grapes imported from Chile, so that every single grape had to be removed from store shelves throughout Canada; the Oka disturbance involving armed First Nations protesters angry at development proposals; a misprinted budget discarded in a garbage pail and given wide publicity before it was scheduled to be delivered in the House of Commons; and so on.”

In choosing public service over his legal career, Hartt “gave up hundreds of thousands of dollars a year in compensation,” Mulroney wrote in his memoirs. The former prime minister considered Hartt to be “one of the smartest young men of our generation.”

Hartt’s 1994 Order of Canada citation praised him as “an articulate advocate for Canada. He has informed Canadians about the inner workings of their government and his experienced advice is sought by both political and charitable organizations alike.”

Norman Spector, his successor as Mulroney’s chief of staff, called Hartt “a first-class intelligence wrapped in a most engaging personality.”

One of Hartt’s “best shticks,” Spector told The CJN, was his impersonation of Mulroney’s nightly phone call “at exactly 10:03,” just after CBC’s The National began.

Spector said that in a “dead-on impersonation” of the prime minister, Hartt would say, “Stanley, did you see it?” to which Hartt would reply, “See what, prime minister?”

After he left the political arena, Hartt served as the chairman of several companies, including the real estate firm Campeau Corp., Citigroup Global Markets Canada and Macquarie Capital Markets Canada. In 2013, he joined the law firm of Norton Rose Fulbright.

He is survived by his four children and seven grandchildren.