“They say time heals all wounds, but that presumes the source of the grief is finite.” Cassandra Clare, Clockwork Prince

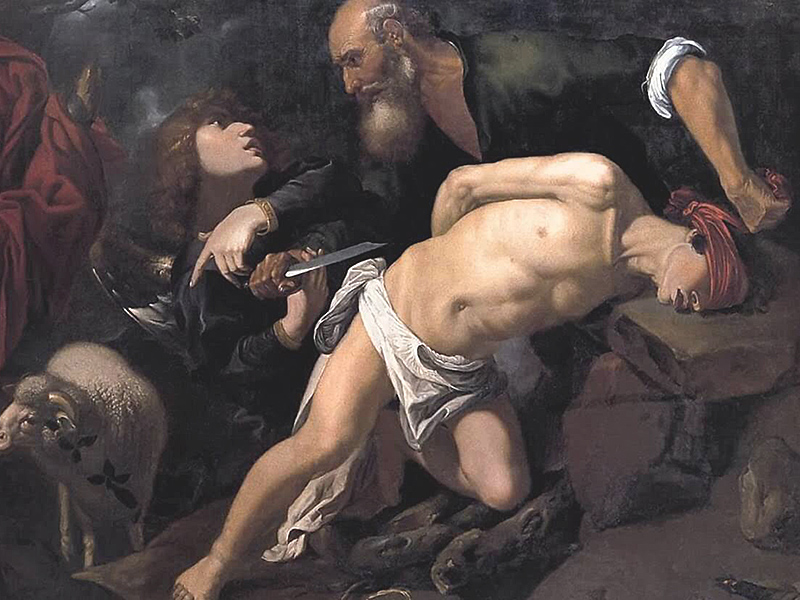

It is said, that when Sarah, the matriarch, heard that her husband, Abraham, was taking their son, Isaac, to be slaughtered – the Akedah – she herself perished out of grief. What would have caused her to do so? Why could she not have survived, despite the fact that her son was about to die?

Grief is a lonely matter. It is a condition from within that causes a person to feel great loneliness, to stare at his or her dreams, to go to a place without hope. “If my son, Isaac, is to die today,” perhaps Sarah said, “then I cannot live anymore because he is the reason I breathe. His dreaming is my dream.”

And is it not possible that Sarah added, “I cannot bear the pain I will feel because of my boy’s demise, and while time might heal all, I would prefer the hands of my internal clock to slow and then stop, for life is not worthwhile without the love of his gaze”?

Why is it that Sarah did not outlast her grief, while others do so?

Could it be that when she heard of the Akedah, grief set in, in the worst way possible? She believed her son was gone, and her maternal love was now without a subject. For she loved Isaac with her entire being.

Abraham, her soulmate, was the executioner, and her relationship with him was beyond repair. How could she show affection to the man who consciously drew a knife from his scabbard to murder their progeny – a boy who had not arrived easily?

READ: Trying to make sense of the senseless

And worst of all, God was cruel. Her faith in God was jaded. How might she pray to the King of Kings, the Father of all creation, when part of His plan was to take back her son, Isaac, a child she never believed could be born from her aged womb?

So Sarah’s sorrow was great. She grieved to death. All she wanted was gone. Nothing she cherished remained. And she died. Her heart stopped. And she was buried in Hebron, a grieving soul. Nothing else.

I have seen grief countless times in my lifetime, as you have. The grieving daughter. The grieving son. The grieving father. The grieving mother. The grieving grandparents. The grieving friend. The grieving community. A grieving nation.

Its colour – grief, that is – is a sort of grey, on a monochromatic palette of feelings mixed with a fluid we call tears. He who grieves sits before you, at arm’s length, yet his presence is adrift, miles beyond the stratosphere, unable to join those experiencing life with joy.

It is true that some, like Sarah, will not outlive their grief, for it is all-encompassing and blocks the way so that the sad one cannot move. And then there are others, who experience loss on a level that seems impossible to overcome – like the concentration camp survivor whose entire family was wiped out. Yet, they do.

Grief is grief. The griever is not to be judged or second-guessed. The level of pain one experiences through grief is one’s own, not at all belonging to anyone else. Yet, there is one thing we can wonder about. Why did God make grieving so harsh?

“The darker the night, the brighter the stars, the deeper the grief, the closer is God!” Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment.

Reach Avrum Rosensweig at [email protected]