The little wooden box, its cheerful floral designs now faded with age, was always out somewhere in my parents’ Toronto home. It was handy for storing odds and ends, or maybe a fishing lure after it wound up at their northern Ontario cottage. At the moment, however, it finds itself in a glass case, on display in a museum in the Czech Republic, an unexpected fate for a humble object that has done its share of long-distance travelling.

In 2017, I was contacted by the Low-Beer Villa museum in Brno, the country’s second largest city, and learned to my astonishment that it was researching my family history. Could I shed light on the textile industrialist Moriz Fuhrmann and the company he founded in the 19th century, the museum asked. And what about his two sons, who took over the firm after Moriz’s death in 1910, and his grandson (my father) who ran it from 1945 to 1948. What was their fate?

Once prominent in Brno, the Fuhrmann family was now something of a mystery for the museum, which occupies Moriz Fuhrmann’s former home, a coral-coloured mansion that he built across from the city’s main park. None of his descendants have lived in what is now the Czech Republic for 70 years – not since my father left after the 1948 communist coup. But with that emailed inquiry, a trove of stories were uncovered.

There’s Moriz Fuhrmann, the self-made tycoon who rose from village schoolteacher to the heights of Brno’s social elite when the Czech lands were still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. There’s the theft of the eponymous Moriz Fuhrmann company during the Second World War, when it was considered Jewish property that was ripe for the taking. And there’s the restitution of the firm after the war, followed by theft No. 2, when it was nationalized by the communist state. And then the epilogue, when my parents jettisoned everything to start all over from scratch.

The world they left behind has tugged at me since I was a child, but I never imagined anyone else cared much about these stories – least of all a museum in the country my parents fled. But at a time when the Czech Republic is marking the 100th anniversary of Czechoslovakia, there is renewed interest in Brno’s prewar German-speaking Jewish business class, which had a major influence on the city’s economy and culture, according to historian Jakub Pernes. Brno was once known as the “Moravian Manchester” for its booming textile sector.

Fuhrmann factories in Brno and Hlinsko, which is west of the city, made carpets that were shipped around the world, as well as jersey that was popular with garment manufacturers and faux fur that trimmed Bata snow boots. Moriz’s home, an Art Nouveau villa that was sold a few years after his death and served as a Gestapo centre during the war, is now owned by the South Moravian Region. After a major restoration, it became a branch of the Museum of the Brno Region in 2015.

READ: CANADIAN RECEIVES ACCOLADES IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC

Last summer, I sent Pernes, a curator at the Low-Beer Villa museum, details of the long conversations I had with my father about his past, almost three decades ago. A dutiful, prodigiously hard-working man then in his mid-70s, my father was unused to such attention. The past had been buried in the effort to make something of himself in Canada. Never had he been given any reason to believe his life merited special consideration. But he took pleasure in recalling the hum and din of textile machinery, the looms, skeins, bobbins and shuttles, as if the act of remembering served to validate the interrupted course of his life. I also sent Pernes various documents and mementoes that survived.

Together with archival material that Pernes found, many of my contributions have been included in “The Textile Company Moriz Fuhrmann 1918–1948,” an exhibition that runs until the end of December.

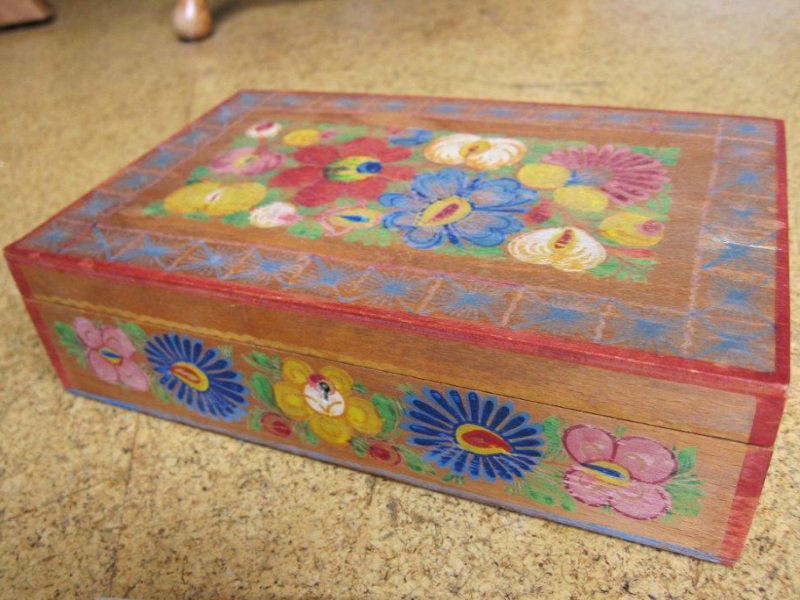

At the Sept. 6 opening, I had the surreal experience of seeing museum visitors – strangers – studying objects that until then were of interest only to me: old photos of Fuhrmanns skating, doing office work and clowning around in their luxury cars; my father’s textile school report card from 1933; military ID tags from his wartime service with U.K.-based Czechoslovak expats; a prewar photo of his father, Hans Fuhrmann, looking self-assured in a business suit, oblivious to the terrible fate that awaited him; a newspaper notice placed by my father upon his return to Brno in 1945, seeking information on Hans and other missing relatives; and that box, a welcome-home gift to my father from the company’s workers after the war.

Brno residents have been drawn to the depictions of everyday life, which depict an “exotic” social class as “people of flesh and blood,” Pernes said recently over the phone. But for me, it was more personal. During the opening, an image of Moriz Fuhrmann was projected over a fireplace in the museum’s main foyer – formerly the centre hall of his home. A local TV crew asked me how I felt about the exhibition and I mumbled something about the impact of standing in Moriz Fuhrmann’s palatial digs, a storied place in my family history. But I was unable to adequately describe my rather dazed state of mind at seeing these Fuhrmanns in the spotlight – or to say how much I wished my father, Robert Fuhrmann, who died in 2001, had been there for the occasion.

In that moment, I felt that history sometimes plays out as it should. It felt like a confirmation that their lives mattered.