In honour of Canada’s 150th birthday, The CJN presents essays on 10 significant moments in Canadian Jewish history.

On Aug. 16, 1933, during a semi-final softball game between Harbord Playground and St. Peters Church in Willowvale Park (now known as Christie Pitts) in Toronto, a huge swastika flag was suddenly unfurled to shouts of “Heil Hitler!” This provoked outrage and retaliation among the Jewish baseball players and spectators. Reinforcements for both sides poured in from nearby neighbourhoods. The result, never experienced in Toronto before or since, was a four-hour race riot, which sent many to hospital.

Tensions had been mounting in the Jewish community throughout that hot summer of 1933. Residents in the eastern beaches of Toronto – provoked by what they thought of as a “foreign invasion” of their district – had formed themselves into “Swastika Clubs” earlier in the summer. On the evening of August 1, the first Swastika Club march was held along the boardwalk, from the Balmy Beach Canoe Club to Woodbine Avenue. A group of more than 100 swastika-sporting youths paraded down the eastern beaches boardwalk, singing an anti-Jewish doggerel to the tune of Home on the Range: “O give me a home, where the gentiles may roam, where the Jews are not rampant all day; Where seldom is heard, a loud Yiddish word, and the gentiles are free all the day.”

This infuriated Jewish visitors to the city’s lakeside recreation area, as, even back then, when Adolf Hitler first came to power, the swastika had become a symbol of persecution, torture and death for the Jews.

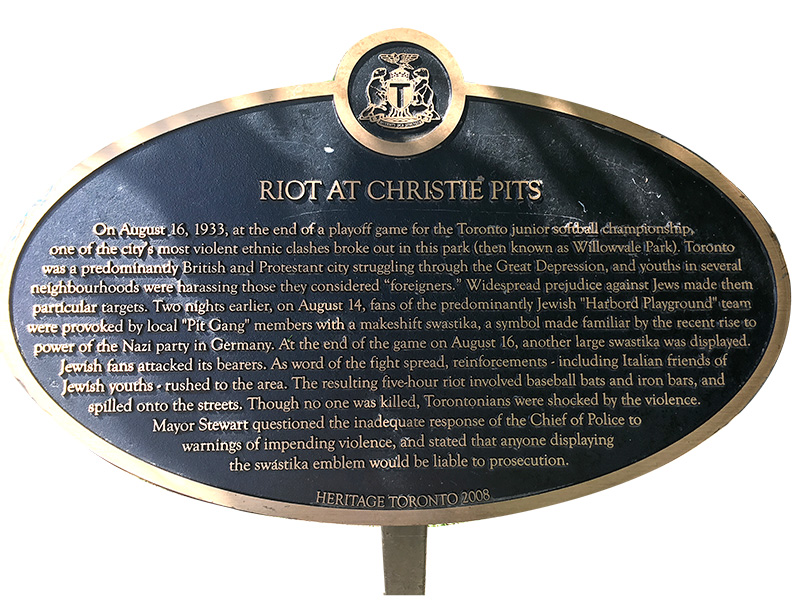

Celebrated journalist Robert Fulford once described the riot as “part of the mythology of Toronto’s history” and urged us to write a book about the event. Subsequent to the book’s publication, the city of Toronto commissioned a plaque at the park, with a brief description of the riot. The riot was a significant moment in the history of Toronto’s Jewish community, for several reasons.

First, it represented a direct response by several hundred Jewish youth to numerous blatant and relentless anti-Semitic provocations throughout the summer, against the backdrop of Hitler’s coming to power in Germany, which was astonishingly well-covered in the English-language press, and in the Yiddish paper, at the time. Reports of violent attacks against Jews in Germany were daily fare. And indeed, without the stories coming out of Germany, the almost daily editorials and letters to the editor on Hitler’s rise to power and the examples of resistance and protest that the newspapers reported, it is highly unlikely that the riot at Christie Pits would have happened at all.

READ: THE CJN’S SPECIAL COVERAGE OF CANADA’S SESQUICENTENNIAL

That summer was unbearably hot, unemployment was rife and hunger was widespread. The Orange Order dominated at city hall and monopolized the jobs in the civil service. Restrictive covenants on housing, rent exclusion, as well as anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish attitudes reached into all areas of the general culture. Elements of Jewish youth broke with the passive, “sha shtil” attitude of their parents. There was no Canadian Jewish Congress, no Anti-Defamation League, no Civil Liberties Association, no ecumenical movement to speak to power in those days. At Easter, many churches taught that the Jews had killed Jesus. Vicious stereotypes of minorities abounded in polite society.

Second, then-Toronto mayor William James Stewart, frightened by the outbreak of violence in the park, called on the chief of police to account for the lackadaisical response by his men, who were warned of trouble at the park that afternoon, but who did not send extra officers in anticipation. Reinforcements were only sent, some say, when it became apparent that the Jewish boys were acquitting themselves well in the street brawl. And although the Jewish youth involved were severely scolded by their parents for fighting with the “goyim” in the park, they were proud of their actions and of their scars. Jewish pride had been restored.

Many Jews claimed to have been involved in the riot – and some exaggerated accounts put the number of people present in the park that afternoon and evening as high as 15,000, but our far more conservative estimate suggests that the actual number of participants in the fighting on both sides was around several hundred. The fact that many more claimed to have been involved in the action testifies to the great pride it engendered among Jews at the time and among those of subsequent generations.

Third, the riot caused anti-Semitic provocations to be taken more seriously by the municipal government, not necessarily because it was opposed to anti-Semitism, but because it was fearful that such provocations would lead to further violence and hence become a threat to “peace, order and good government.”

Fourth, the Italian boys who went to the park to fight alongside of the Jews demonstrated that the anti-Semitism they experienced was embedded in a more general xenophobia, which included anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiments. Our Italian respondents told us of the prejudice that they experienced at the hands of their WASP neighbours at the time, because they were both immigrants and Catholics. The Jews and the Italians were neighbours in the Wards 4 and 5 areas of the city, and shared the common fate of outsiders linked by poverty and experiences of prejudice and discrimination (one of our Italian interlocutors spoke to us in passable Yiddish).

Fifth, the riot became a marker of remembrance, pride and resistance not only for the generation involved in the riot, but for successive generations of Jews. If anything, the mythology surrounding the riot grew with the experiences of the Shoah and the various wars waged against the State of Israel.

Finally, learning about the riot has helped the city come to grips with a less savoury aspect of its past – with its racism, anti-Semitism, xenophobia and the prejudices, discrimination and exclusion involved with all of that. The plaque that the city unveiled near the southeast corner of Christie Pits that tells the story of the riot, represents a genuine attempt by the municipal government not only to give historical testimony to the event, but to expose the conditions that led to the outbreak of violence on that hot summer afternoon in 1933.

Cyril Levitt and William Shaffir are the authors of The Riot at Christie Pits, a new edition of which is being published in August by New Jewish Press, the publishing program of the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies.