“No book in Jewish history has been illustrated more often than the haggadah,” writes renowned University of Toronto scholar and art historian Adam S. Cohen with confident certainty.

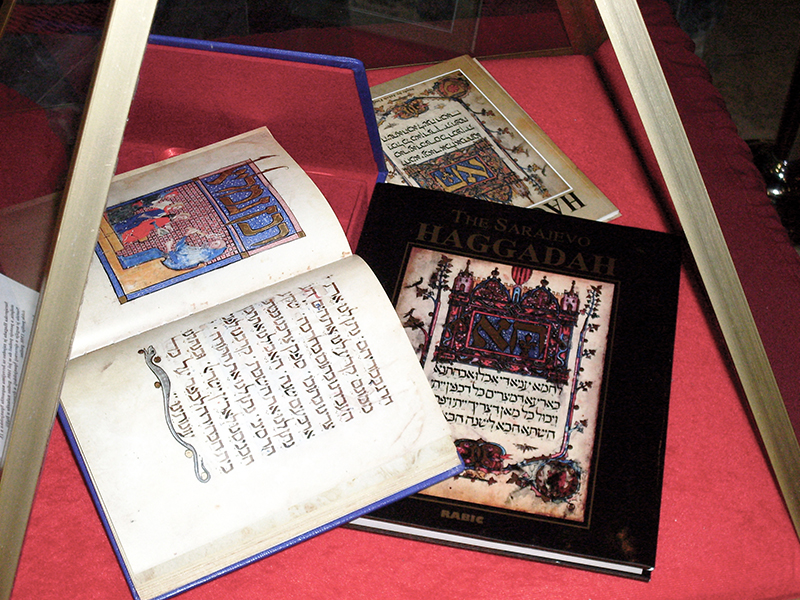

In his recently published magisterial work, Signs and Wonders, Cohen examines 100 haggadot from the 13th century to 2014, exploring “the remarkable creations that constitute the visual heritage of the Passover haggadah.”

The first written haggadah, Cohen tells us, appeared in around the eighth or ninth century. The earliest illustrated haggadot appeared in Europe in the 13th century. For the next 700 years, “the haggadah would be one of the most popular books among Jews, first as handwritten manuscripts and later as printed books. Thousands of editions have been produced in every country Jews have lived, often with translations into the many languages they have spoken and read.”

This should come as no surprise. We see proof of the haggadah’s ongoing popularity every year, as Pesach brings a stream of new haggadot onto the shelves of book stores, both physical and online, and Judaica shops in every community where Jews reside.

The narrative in the haggadah contains a number of key literary ingredients: compelling characters, high drama and ultimate redemption. And its message – or, rather, the many messages in the haggadah – have resonated with profound meaning across time and space since the story was first recounted some 3,300 years ago.

READ: THE EVOLUTION OF THE HAGGADAH – A COLLECTOR’S PERSPECTIVE

The late Rabbi Philip Goodman, a compiler for The Jewish Publication Society’s Jewish holiday anthology series, perfectly expressed the enduring magnetism of that message: “The spirit pervading the haggadah is one of longing for redemption and freedom, a belief in the survival of the Jewish people and an unyielding confidence in divine salvation. It was, therefore, natural for this work to capture the hearts of the Jewish people in all generations and to give us a sense of pride in Jewish destiny and broad perspectives on the precious values of freedom and liberty for all mankind.”

But perhaps the reason that best explains our unbroken embrace of the haggadah is the fact that in each generation, parents actually do faithfully take up the enduring responsibility of recounting the story of Pesach to their children.

As Cohen points out, Signs and Wonders is more than a work of art history – it is also a work of Jewish history. The uniqueness of each illustrated haggadah is a testament to the artistic creativity, skill and Jewish expression of the men and women who lived in those particular communities.

“Despite the wide variety in artistic approaches over the course of seven centuries, it is notable that a dominant and recurring idea expressed by the pictures concerns the intrinsic links between past, present and future. Over and over again, the illustrated haggadot affirm that the actions of this seder – the one enacted by the participants looking at this particular haggadah at a specific moment in history – are inextricably bound with seders of the past. They express the Jews’ continued relationship to God, no matter what the present circumstances and a demonstrable yearning for a better time, summed up in the closing declaration of the haggadah: ‘Next year in Jerusalem!’ ” writes Cohen.

Throughout the years, commentators have noted in their treatises on the haggadah that the biblically based requirement to tell the story of Pesach to our children is the core requirement of Judaism itself. Teaching our children the beliefs, traditions, history and literature of their people is the best way to achieve – for all time – our “continued relationship to God.”

And, of course, that requires an education system that is accessible to all the children in the community. There is no other higher obligation for community leaders than this.