“Sword into plowshare, plowshare into sword…”

There is nothing like cleaning up for Passover. You find things that had long been lying in the bottom of that drawer you had not emptied, thinking that you would get to it soon. Thus it remained hidden until the urge to purge came upon you – that need to clean out all the chametz.

So in this process, I came upon a long-unopened folder of articles written ages ago for the Canadian Jewish Chronicle.

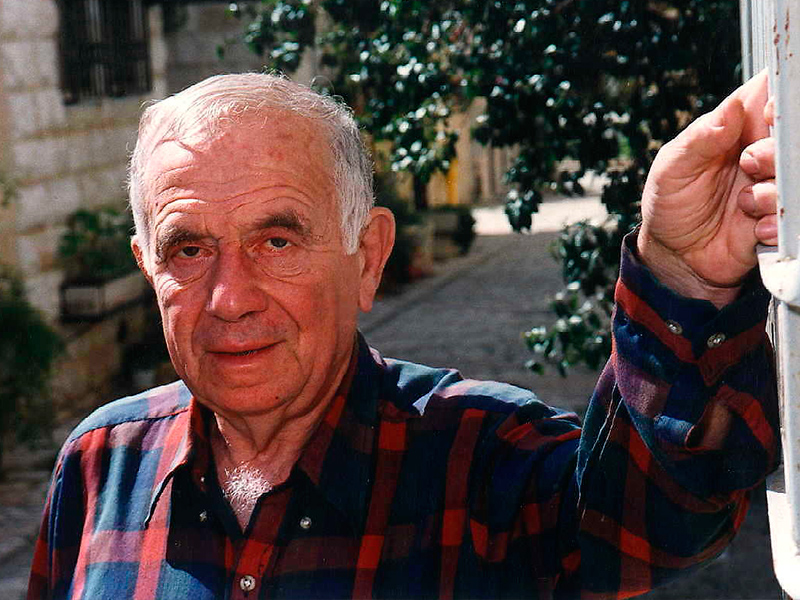

In it was an interview I was privileged to conduct with the late Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai, a timely discovery given that we recently marked Lag b’Omer.

Actually it is not the Lag b’Omer celebration that I am thinking of, but rather the ugly, horrific, devastating and catastrophic war that the 33rd day of the Omer has as its backdrop: the Bar Kochba war, which ended so tragically at the last fortress of Betar.

Bar Kochba/Bar Kosiba: we have no information on his birth, early years, family, education – only on his leadership of the eponymous uprising. Obviously, he was a charismatic leader, since he raised an army of rebellion a mere 60 years or so after the debacle of 70 CE. What we usually remember about the war are stories of the 10 martyred rabbis, or his army’s heroic last stand at Betar. These are stories crafted by wearied survivors of that time, including an account of the cessation of the plague that ravaged his army on Lag b’Omer.

Bar Kochba, despite his early successes, was no messiah. Rabbi Akiva’s naming of him (his name was not Bar Kochba) as the messianic “son of a star” drew this reproof: “Akiva, grass will grow out of your cheeks before the Messiah comes.”

And so it proved. Rome came down like the proverbial wolf on the fold and demolished Judea. Jerusalem, already half destroyed, was plowed under. Jews were sent fleeing north and west, leaving huge tracts of the land empty. It took several centuries for new towns to be built. The slave markets were over-subscribed with Jewish prisoners. Some ended up in the gladiatorial ring.

No doubt Bar Kochba’s soldiers fought believing that they could evict the Romans from their beloved country, not realizing that they were living a dream – the Romans were living the reality. Bar Kochba became a symbol of two divergent trends: failed messianism, or heroic resistance.

For me, Lag b’Omer is a 24-hour period when we can catch our breath, and not a time for wild rejoicing. That said, I found the Lag b’Omer celebrations in Israel to be fun, with bonfires and kids’ playtimes extended into the night.

Now back to the present and to poetry. It is no secret that Amichai was not a proponent of messianic expectations, or of the final efficacy of settling problems with war.

“People,” he said, “always think their war will be the last.”

A poem that he read the evening of our interview so long ago combined hope and reality. He told his audience that if there were any underlying themes to his poetry, they were wars – all the wars of many lifetimes of Jews – and the opposite to war, love.

Here is the version of the poem he offered:

The man under his fig tree

Telephoned the man under his vine

Tonight they definitely might come

Armour-plate the leaves

Secure the tree…

The white lamb said to the wolf

The human race bleeds

And my heart aches

No doubt there’ll be close combat soon

At our next meeting we’ll discuss it

All the nations – united

We’ll stream into Jerusalem

To see if the law went forth from Zion

And meanwhile

Seeing it’s now spring there

Pick flowers

And beat sword into plowshare

And plowshare into sword

Then back again and again without stopping

Maybe from so much beating and grinding

The iron of war will die out.