My relationship with Philip Zucker began 54 years ago, when my parents hired him to teach me all of parshat Tetzaveh and the special Maftir and Haftorah for Shabbat Zachor as part of my bar mitzvah preparations. Despite his death on Feb. 18, that relationship continues.

Zucker was born in the Polish town of Serock, not far from Warsaw, on Nov. 11, 1918. His mother gave her father the task of registering the birth, but he did not get around to it until January of the following year. Because Zucker’s parents would have been in trouble for not registering his birth within 30 days, his grandfather indicated that Zucker had been born in 1919. Consequently, when World War II broke out years later, Zucker was not yet of conscription age. He likely avoided being killed fighting a hopeless battle against either the Russians or the Nazis.

In September 1939, the Germans entered Serock, rounded up Zucker and his father, along with all the other Jewish men, and marched them toward Germany. But before arriving, the Germans realized they had made a mistake. Pursuant to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Serock actually belonged to Russia. And so the Jews were marched east to the new Russian border. Instead of perishing in a death camp in Germany, Zucker survived in a labour camp in Russia.

READ: THERE WILL NEVER BE ANOTHER ‘DR. JOE’

He arrived with his wife and first child in Toronto in 1949 and found two jobs: sewing coats on a piecework basis in a factory owned by his wife’s cousin, and as a ba’al koreh (Torah reader), first at the Shaw Street shul, and later at Shaarei Shomayim, where he also starting working as a bar mitzvah teacher, preparing young boys to become men.

In 1962, Jack Burke, the Hebrew vice-principal for grades 7 to 9 at the Associated Hebrew Day School, made him the recommended bar mitzvah teacher for students who did not otherwise have one. Zucker was able to give up working at the shmatte factory. On his last day of work, his wife’s cousin told him, “You were never good at this. You always did a perfect job when you could have gotten by with less and made more money.”

Zucker was stubborn and uncompromising when it came to the ethical standards he set for himself. For him, reading from the Torah wasn’t a simple matter of singing the notes. He lived the words, and he demanded perfection. If the Torah spelled a word with the letter vet instead of bet, it was for a reason. If the note indicated was a geirshayim, it was not – could not – be mistaken for an azla geireish.

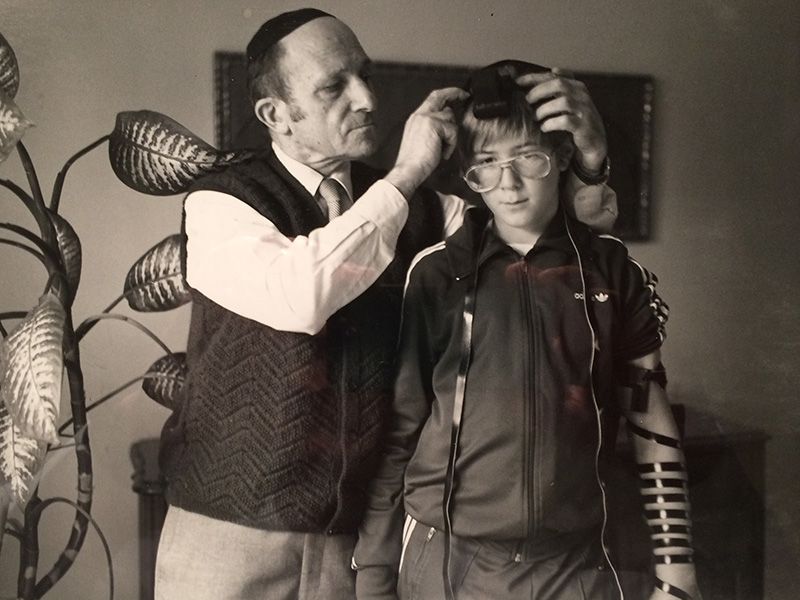

Our learning sessions were slotted for Saturday nights, and so, as soon as Shabbat was out, I would take the bus to his house at 55 Burnside Dr., where I would sit at his kitchen table facing west, with him to my left facing north. He was the most gentle and patient of teachers. When I made a mistake, his right hand would touch my left wrist and he’d wait for me to figure out my mistake. He never looked at the tikkun (the book I was studying from to learn the layning). He didn’t need to.

Many years later – I think he was 96 at the time – I paid a visit to my old bar mitzvah teacher, When I asked him how he was, he responded, “Not so good. My memory’s declining.”

“That’s not true,” I said. “And I’ll prove it you.”

I sat down at his table, on which, as always, were his magnifying glass and the Epstein Chumash he favoured. I asked Zucker to sit down too. By chance, he once again sat to my left, facing north.

“Now I’m going to start reading,” I said, “When I stop, you will recite to the end of the Torah, from your memory alone.”

I had read about five words when, just as he did so many years before at 55 Burnside, his right hand touched my left wrist. I had made a mistake. He was not looking at the book. And still he caught it.

Zucker viewed his life as having been determined by goral, a Hebrew concept situated somewhere on the vast continuum between pure chance and divine providence.

He lived his life according to the Torah precept of humility. In over five decades of knowing the man, I had never heard him say anything even remotely boastful. So it was with hesitation that he explained to me that when the great Jewish thinkers would come to speak in Serock, his father would take him along to listen. Walking home, he told me, he would recite back to his father every single word they had heard, using the proper inflections and speaking style. But he could no longer do that sort of thing. That was his failing memory.

One cannot leave one’s intellect as a legacy to others. Zucker’s legacy is that of a silent mentor who guided others by the example of his life, without even knowing he was doing so. Years ago, I met one of his sons-in-law and began telling him about the esteem in which I held Zucker. “I know,” he said. “When my sons have an ethical problem, they ask themselves one question. ‘What would Zaide do?’”

There can be no higher tribute.

Murray Teitel is a Toronto barrister and freelance journalist. He was also one of Philip Zucker’s approximately 2,000 students.